The eight-metre tall Pillar of Shame statue connects a Danish artist, China and Hong Kong with the commemoration of 1989 Tiananmen Massacre victims. It also reflects the development – or perhaps the deterioration – of democracy and human rights in Hong Kong.

“The old cannot kill the young forever,” is engraved on the base of the pillar – above it, a towering entanglement of human suffering cast in bronze, copper and concrete. Its Chinese name, meaning “Pillar of Remembrance” or “Pillar of National Grief,” was translated by the late pro-democracy politician Szeto Wah, who formed the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China in May 1989 before the June 4 massacre.

The pillar, created by Danish artist Jens Galschiøt in 1996, was moved to the University of Hong Kong campus by students in 1997 right after being exhibited at the annual candlelight vigil in Victoria Park. Former lawmaker Albert Ho, now chair of the Alliance, recalled why they decided that the statue must be transported to Hong Kong before the 1997 Handover to China.

“We fought for the statue to be shipped to Hong Kong when it was still under British rule. At that time, we had good reason to believe that this statue would not be allowed to enter after the transition,” Ho said.

The Tiananmen massacre ended months of student-led demonstrations in China as the People’s Liberation Army was deployed to crack down on protesters in Beijing. UK Foreign Office files declassified last year revealed how a member of the Chinese State Council suggested that at least 10,000 civilians were killed, though estimates of the death toll vary.

In the early hours of June 5, 1997, amid scenes of confrontation with HKU campus security and the police, students managed to enter the campus by insisting it was a private area.

“I said at the time – the only way to peacefully resolve the matter was to allow the pillar to enter,” Ho said.

A secondary school teacher, who was in his first year of study at HKU at the time, told HKFP that he was a moderate student, but he believed the student union was doing the right thing and so joined in support.

“It was just before the Handover – as a year one student, I felt something has to be done,” he said. “But I did not expect a clash would happen.”

He said he was at the back of the crowd, but was gradually pushed to the front, as the confrontation continued until 3am.

“When the school made a compromise, I was glad – I had done something meaningful,” he said.

“I did not think the incident would be so influential. To me, the Pillar of Shame was a symbol of the fight with crimes against humanity. We refused to let go,” he added.

The pillar was then exhibited at several universities, before the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Polytechnic University erected their own Goddess of Democracy statues years later – tributes to the one erected by the Tiananmen students. In 1998, HKU’s student union hosted a referendum which gave a mandate for the pillar to remain permanently at the school.

However, the pillar did not disappear from the headlines. In 2008, the Alliance painted the statue orange in support of Galschiøt’s “The Color Orange” campaign, which aimed at highlighting China’s human rights violations, on the occasion of the Beijing Olympics Games.

The colour, according to the artist, was a mixture of red, representing the dictatorship of China, and yellow, representing freedom and human rights.

Galschiøt was invited to Hong Kong on April 30 that year – 100 days before the Olympics – but he, and his two sons who accompanied him on the trip, were denied entry at Hong Kong’s airport. After a seven-hour interrogation, they were sent back to Denmark for failing to satisfy immigration requirements.

The Alliance invited the artist to Hong Kong again in May 2009 to participate in the maintenance of the pillar and events commemorating the 20th anniversary of the massacre – and he was once again denied entry. The artist’s next attempt to enter Hong Kong in 2013 was allowed.

Every year since 2002, the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China has cleaned the pillar ahead of the anniversary of the massacre. This year, the ritual was held on May 4 – the 99th anniversary of an anti-imperialist movement in China led by students.

Albert Ho said the washing of the pillar on May 4 held a special meaning, as students were on the front lines of both movements.

“The symbol of this action is to show that we are still persisting with our dedication to the movement. Every year when we come to clean and wash this Pillar of Shame, we are trying to rejuvenate the spirit of young people,” he told HKFP, adding that it was to tell students the history of how their predecessors moved the pillar into the university.

After 2014, as students grew more and more distant from the Alliance’s patriotic ideals – namely “building a democratic China” – HKU students washed the pillar separately.

Ho said the Alliance was in communication with student groups, and that it did not matter if they held the washing ritual together on the same day or not, as the student groups will plan their own washing of the pillar.

“We agree the same thing – to commemorate those people, including young students, who dedicated their lives for the cause of democracy.”

Asked whether he was worried that the pillar would not be allowed to stay at HKU now that the political climate is changing and with a mainland-born vice-chancellor at the helm, Ho said he believed the pillar would remain.

“I believe any attempts to move the Pillar of Shame would symbolise a complete stripping of the university’s freedom of speech and expression,” he said.

“The pillar standing here symbolises not only its basic values – of the fight for freedom and the fight for democracy – but symbolises an even more fundamental thing, which is freedom of expression. So I think no one will dare challenge this core value.”

“I hope the school understands that free thought, free speech, free expression, and free research are most important. If even these freedoms are gone, then the school should be closed down.”

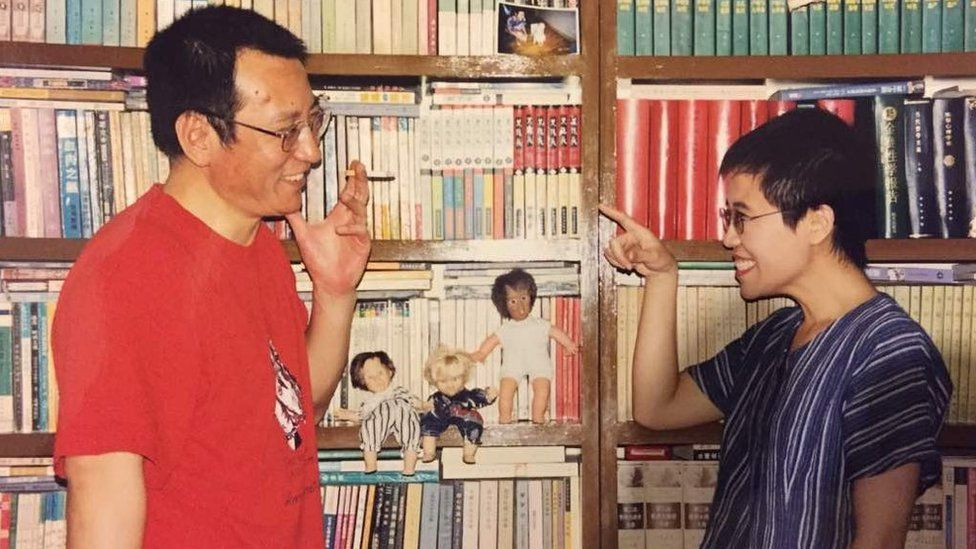

During the 1989 movement, the late Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo was known as one of the “Four Gentlemen” of Tiananmen Square. His group staged a hunger strike in the final days of the protests, in hope of holding off a military clearance.

His widow Liu Xia has been effectively under house arrest for years, although she has never been charged with a crime. A recording of Liu Xia emerged this week, in which she said she is ready to “die at home” in protest of her continued detention by Chinese authorities.

Albert Ho said Liu suffered psychological hardship from her treatment by authorities.

He said it was a disgrace that the Chinese authorities may use the freedom of Liu Xia or detained human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang as a bargaining chip in its trade discussions with foreign governments calling for their release.

“Some humane foreign countries care about the freedom of we Chinese people, and care about the dignity of our people, but this is how our Chinese government behaves.”

He said the Chinese government should let Liu Xia go to Germany. “If you still block her, I’m worried – many people are worried – that she will use death to resist.”