2017 was not among the best years for human rights journalism, and human rights are not a high priority for most governments around the world at the moment, but it was an astoundingly good year for books about human rights. Writers and publishers care more than ever before about a wide range of human rights issues. And if publishers care, that means they think there’s a readership out there for these books.

If, looking around the world today, you are tempted to pessimism, many of the books on the list show that in many areas, there has been substantial progress in recent decades. That recognition should not be grounds for complacency: The situation in many places and on many issues is dire, and there are plenty of books on the list which show that as well. This year’s list includes an unusually large number of books about democracy, and in particular the threats it faces, reflecting an awareness that it has deteriorated due to a combination of a rise in authoritarianism and the dominance of the neoliberal economic agenda. Human beings’ capacity for cruelty, brutality and bigotry is also well represented. History suggests that it is within our capacity to progress but also to regress. The books on this list, as a whole, are messages of both hope and warning.

-

Photo: UN.

There are 46 books on the list proper. In addition to those 46, there are 30 other books that I was not able to read in their entirety but nevertheless recommend.

58 publishers are represented, from commercial giants to small independents to academic presses.

The 76 books are about 29 different places, including Catalonia, China (8), Egypt (3), El Salvador, Hong Kong, Hungary, India (3), Iraq, Japan, Kenya, Laos, Liberia, Namibia, North Korea, Pakistan, Palestine (3), Russia (5), Saudi Arabia (2), Somalia, South Africa, South Korea (2), Syria (6), Taiwan, Tibet, the United Kingdom (2), the United States (26), Vietnam, Latin America, and the world (8).

The books are about a wide range of rights issues, including migrant rights and in particular the rights of refugees and asylum seekers; children’s rights; the right to education; enforced disappearances and extrajudicial detention; genocide; war crimes; crimes against humanity; self-determination; colonialism and occupation; LGBT rights; women’s rights; indigenous peoples’ rights; disabled people’s rights; caste and racial discrimination; labor rights; property and land-use rights; housing rights; human rights defenders; democracy and dictatorship; activism and advocacy; civil disobedience and nonviolent revolution; corruption; freedom of religion; neoliberalism and democracy; freedom of speech; freedom of assembly; poverty; the right to health; the right to food; the right to due process and equality before the law; police violence; extrajudicial killings; slavery; cultural rights; prisoners’ rights; and torture.

As that list indicates, “human rights” is here understood as those rights contained in the two principle covenants, the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, as well as in the international human rights treaties that emanate out from them, and issues related to their abuse, protection and defense, and the nonviolent struggle for their fulfillment. Worth noting is that books related to democracy are included on the list, since it is a right in itself (ICCPR Article 25) as well as the form of government which in itself embodies the best fulfillment of rights and in practice best guarantees their protection.

Several human rights issues are under-represented on the list. There is little directly about the right to privacy, especially given the enormous increase in high-tech surveillance and monitoring. There is no book directly about freedom of expression, though several books touch on it in relation to other issues. There are only two books squarely about labor rights, though they appear in several others, and no books about economic rights, though several about the deterioration of democracy caused by the reign of the neoliberal economic paradigm. There is no book about environmental rights. There is no book primarily about the rights of disabled people. And while there are many books which indirectly touch on issues related to freedom of assembly and association, none deal directly with that right.

The 76 books on the list are of many genres: reportage (12), history (9), memoir (8), the novel (8), academic studies (8), how-to guides and lessons (6), family history (6), graphic novels/memoirs/reportage (4), children’s books (3), anthologies (4), oral history (2), essays (2), philosophy (2), biography, and short stories. No photography this year, unfortunately.

All books are in English. Eleven are translated, from Arabic (2), Chinese (4), French, Korean (2), Russian and Tibetan.

The general guideline for inclusion is that the book has to be published between December 1, 2016 and December 1, 2017 in the United States or elsewhere, but there are also 12 books published in the latter part of 2016.

Compiled with gratitude to the writers of these amazing books. Always curious to know what I’ve missed. Please send your suggestions.

City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World’s Largest Refugee Camp, Ben Rawlence (Picador)

About Dadaab. You know Dadaab, of course, because you’ve been following the news about the global “migrant crisis”. No? Why not? After all, it’s the largest refugee camp in the world, with upwards of half a million inhabitants, 350,000 of them UNHCR-registered refugees (technically, it’s a town in its own right made up of five distinct camps) in the desert-like nowhere of outback Kenya. If you don’t, you’re hardly alone. In the media, refugees from Syria have received the most attention, understandably so, though to a large extent, that’s because so many have made their way to Europe and, to much lesser extent, North America. Meanwhile, many other places continue to face chronic refugee crises. And this account recalls the fact that the countries that take the greatest burden of refugees — Pakistan, Lebanon, Iran, and here, Kenya — neighbor the places from which people are fleeing. Dadaab is the biggest because so many people have been stuck there for so many years. The overwhelming majority of them are from Somalia. As the sub-title indicates, the book follows (or, perhaps I should say gets inside of ) the lives of nine refugees in particular. It is a compelling, well-written narrative of great empathy, a paragon of advocacy journalism. We see all that these people are up against and how forgotten they are by most of the rest of the world, how they deal with the authorities, whether the UN or the Kenyan government, who don’t always seem to have their best interests at heart, and the decisions they make given the limited and difficult options they have. Kenya has said it will close Dadaab. It’s hard to know how it would manage.

Liberationists, a story, Xun Yuezang (Pema Press)

A human rights worker disappears while crossing the border between Hong Kong and China. She is presumed detained by state security. The story is in the second person, in the form of an address from the husband to the abducted wife. It reads like his interior monologue: everything you ever think of when a loved one has disappeared and you feel helpless to bring her back, a testament to an intense and dark period in a life committed to aiding others. With many essayistic passages and philosophical meditations on freedom, rights, democracy and human dignity, Liberationists is about the terrible rights situation in China and the many Chinese who have fought so hard for their freedom and been persecuted for so long, but in its spread and sprawl, it encompasses many other stories as well, of both liberationists and the unliberated, for its essential message is that most all of us are both liberationists, in that we strive for freedom, our own and others’, and unliberated, in that we are not yet free and act in ways that condemn others to unfreedom. The husband’s efforts to procure his wife’s release take him from Hong Kong to London to New York and bring him into contact with many others. There’s the Filipina helper in Hong Kong whose property has been stolen by her unfaithful husband back home, the gay HIV-positive Russian millionaire investing in cutting-edge medical technology and living in the shadow of Stonewall, the Indian Londoner in war zones in Colombia and Gaza, the Tibetan refugee washed up like driftwood in Paris. The young daughter of the disappeared human rights worker, raised by her father in her mother’s absence, comes to play a starring role in one of the most serious depictions of a relationship between a parent and young child I’ve come across. The relationship thematizes, not least, education’s influence on the degree to which a society is democratic and rights-respecting, or not, as the case may be. A unique and special story, of the sort one comes across only once every few years.

The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia, Masha Gessen (Riverhead)

The story of how Russia did not become a free, democratic and open society after the end of the Soviet Union, an essential story for our time. The broad outlines of the story are fairly well known to anyone who’s been paying attention, but what makes Gessen’s telling so powerful is: 1) she follows the lives of four people who were born in the early eighties and came of age during the period of (non-)transition, and 2) she reflects on the sort of society Russia has become: is it authoritarian, totalitarian, something else, something new? And she does this not least of all through recourse to comparing older ideas about repressive regimes to Russian society today. Apart from the four young people, Gessen also profiles a regime-supporting ideologue, a poll-taking sociologist and a psychoanalyst. For me, some of the most interesting parts had to do with exploring the psychology of a populace which to a large extent appears to have bought into Putin and what he supposedly stands for. I was often reminded of China and Hong Kong, and part of the usefulness of the book lies in it being a point of comparison to the many other forms of anti-democracy currently in vogue around the world. Gessen’s already written two excellent books about Russia today, Words Can Break Cement about Pussy Riot and The Man Without a Face about how Putin gained and has retained power, so this book isn’t meant to go into great detail about anti-regime activists or the mechanisms of power. Instead, it’s a kind of biography of a country, and has the feel of a magnum opus about it- this is the book Gessen’s been working on for years. It reminds distantly of Svetlana Alexievich’s oral history, just translated into English last year, Secondhand Time, but whereas that presents voices largely shorn of context, this stitches such voices together, constantly striving to make sense of what’s happened to the country. This honest exploration is a large part of what makes it so interesting to read. Where the four young people are at the end of the story says a world about the sort of place Russia is today. One of the four is gay, and that leads to a chronicling of the homophobic campaign whipped up by the regime and its allies to cynically buttress their rule. I was struck by its similarity to a similar campaign by the Sisi regime in Egypt (see The Egyptians below).

About the struggle to find adequate treatment for AIDS. France directed the excellent 2012 film of the same name. Both book and film are dramatic and inspirational, but the book goes into much greater detail about both the activism and the science, and while the “screamers” got the lion’s share of attention in the film, the book covers a wider array of types of activists and shows how they got the job done and the tensions between them. The period covered is from 1981, when “GRID” — gay men’s immuno-deficiency — was first identified, to 1996, when the first effective drug cocktails to treat AIDS were discovered. Much of the most compelling reading has to do with the lives and motivations of the activists fighting for decent health care and against prejudice, focusing on both individuals and groups in New York such as ACT UP and, later, TAG. France himself arrived in New York from the Midwest in 1981. He was a journalist during the plague years as well as an activist, and he was acquainted with most of the protagonists fighting for adequate treatment. As of 2013, 40 million had died of AIDS, most in sub-Saharan Africa, twice as many as in the bubonic plague which threatened humankind in the fourteenth century. In the US, 658,507 had died by end of 2012; around the world, 2 million still die every year from AIDS, because the cost of effective medicines, though now under a dollar a day, is prohibitive. Still, by 2011, 6 million had access to the drugs that can indefinitely prolong life with AIDS, and by late 2016, 17 million. How to survive a plague is about the right to decent health care, about activism, and about LGBT rights: Arguably, the fight of activists for decent treatment did more than anything else to promote the rights of gay Americans and lead to the breakthroughs in both equality before the law and social attitudes seen in more recent years. In this sense, it is one of the great human rights success stories of our time, though strikingly, by the early nineties, the movement was fractured, depleted and demoralized, just at the moment before the dawn. A good interview with France.

Surprising to see a book as radical as this in tone and outlook published by a mainstream US commercial publisher, especially given that it’s written by a New York City subway conductor originally from Andhra Pradesh. It tells the story of Gidla’s family who are “untouchables”. As such, it is about the most widespread human rights issue of India, casteism and caste discrimination. Horrific and spectacular atrocities and events (think Syria, IS, Burma and the Rohingya) get great media attention, as they should, but to the detriment of chronic rights abuses like India’s casteism or China’s dictatorship which affect hundreds of millions of people. The telling of the family’s story reveals how casteism affects people’s lives, over several generations. The clear protagonist of the story is Satyam, the author’s uncle. Raised a Christian untouchable, he becomes a Communist, turned off by Gandhi’s exhortations that untouchables (or, as Gandhi called them, Harijans, “children of God”) should not “provoke” their caste compatriots, and eventually a revolutionary who disappears into the forests. (The book skips over Satyam’s quarter century in the forest and says little about the life of the author herself- perhaps that’s for future memoirs.) This is excavated history at its best, the sort of history too seldom told, or that too seldom reaches a wider audience, invisible and unwritten history, subaltern history, and from it arises not only a clear picture of how discrimination affects every aspect of these people’s daily lives but also events that have faded from most people’s historical awareness, such as the horrific massacres of Telangana peasants perpetrated by the Indian army on Nehru’s orders not long after independence, in order to uphold the caste order of the countryside. The sort of book that should make it into print much more often.

The City Always Wins, Omar Robert Hamilton (MCD)

About being young and believing you can change the world (or at least your small corner of it, which is in itself immense) and coming up against both the world’s limitations and your own, this novel focuses on well-educated, secular, urban revolutionaries of Cairo (the eponymous city ), caught between contending forces much more powerful than themselves— the Muslim Brotherhood and the army in particular, who are battling to steal the show, and do, first one and then the other. As a reflection on the Egyptian revolution, this is a wonderful book, and even more so as a study of people who have given so much and have not ended up with what they strove for. I read the book as a fellow revolutionary on the other side of the world, coming from the perspective of the Umbrella Movement. The visceral feelings of defeat and disillusionment of the main characters are very similar to those of alienated, pessimistic and depressed young people in Hong Kong. Such feelings lie deep inside you and threaten to destroy everything in your life, including your relationships, if the regime doesn’t first. The substantial difference between Egypt and HK is that in the latter, the regime didn’t kill, torture and unjustly imprison people in large numbers (there are an estimated 60,000 political prisoners in Egypt today). The breathless writing style creates a “you are there” feel, putting the reader at the heart of it all, with prose that often sounds as if it was just jotted down, including text messages and tweets. By the end, death is everywhere, and the tone is mournful and defeated. A brilliant example of how you “literaturize” recent political events, bringing them alive and giving them depth, significance and meaning in a way quite different from good journalism.

The Egyptians: A Radical History of Egypt’s Unfinished Revolution, Jack Shenker (The New Press)

Originally published in the UK in 2016, a rich, deep and wide-ranging account of not only the Egyptian revolution itself but of its background, in particular the many political and economic factors that pre-dated and influenced it, and of its aftermath. Immensely knowledgeable and well-researched. As the sub-title stresses, the Egyptian revolution is neither over nor defeated but unfinished. You can’t keep the people down, at least not forever. Or can you? That’s the drama that’s being played out in Egypt and Syria and China and Hong Kong and Tibet and Palestine and Kashmir and countless other places around the world. The book is divided into three parts, Mubarak Country, Resistance Country and Revolution Country, the first about the Egyptian state under Mubarak and his precursors, the second about the many forms of resistance to its injustice prior to and during the revolution, and the third about the diversity of revolutionary activities in the aftermath of not only Mubarak’s fall, but the overthrow of the Muslim Brotherhood government and the re-imposition of dictatorship. Configured in this way, the revolution is depicted not as a one-off event but as a massive eruption in a larger, longer-term struggle.

Human Acts, Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith (Hogarth)

Originally published in Korean in 2014, out in English in the UK in 2016, first appearing in the US this year, Human Acts focuses on the Gwangju uprising and massacre of 1980, one of the seminal events leading ultimately to South Korea’s transition to democracy. Han Kang has said that the novel is her struggle with the riddles of human violence and human dignity and that Gwangju is emblematic of the atrocities of the 20th century, from Auschwitz to Nanjing to Bosnia and the Korean traumas of the Japanese occupation and civil war. The novel is divided into seven chapters, each told from a different character’s point of view. What all seven have in common is that they have some relation to the events of Gwangju in 1980. The first chapter is told by The Boy, fifteen-year-old Dong-ho who, in search of his missing friend, ends up helping to care for the corpses of the murdered and is then in turn himself killed. The second is by The Boy’s Friend, the one Dong-ho was looking for, who has also been murdered. From there, the narrative jumps forward in time, eventually all the way up to 2013, told by a newspaper editor, a prisoner who was tortured in the massacre’s aftermath, and a factory girl who was brutalized at Gwangju. The penultimate chapter is told by the mother of Dong-ho, and the last chapter by the author, whose family was originally from Gwangju but left months before the uprising, selling their house to Dong-ho’s family. As that structure suggests, the story is about how such a traumatic event “lies in the bones of a people” for years afterwards and affects their lives at a very profound psychological level. It is about coming to terms with a dark period of a people’s history and shows how that unresolved history continues as an often unspoken and unregarded undercurrent. The prose is spare, and the story reads like a dirge, a requiem. Its severe, somber tone and precise, chiselled style bear resemblance to Anuk Arudpragasam’s The Story of a Brief Marriage on last year’s list. Han Kang’s The Vegetarian received wide acclaim in the English-reading world last year, and while that too has its merits, Human Acts is better.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, Arundhati Roy (Knopf)

An ebullient, messy, baroque, melodramatic tapestry of a messy, baroque, melodramatic country. A fairy tale of the oppressed and marginalized, Roy’s second novel, two decades after her first, The God of Small Things, tells two stories that eventually come together in a graveyard not of the dead but of the living, the survivors of India’s multiple atrocities big and small. The first story is about a hijra of Muslim background, and the second is about a Kashmiri freedom fighter. Along the way, many of the other major human rights issues of recent Indian history make an appearance, such as the Gujarat pogroms. The leader of Gujarat at the time, allied to the Hindu extremists who were the pogrom’s main perpetrators, is now the leader of India. The Kashmir sub-plot is more straight-forward. I found it more compelling. It focuses on a doomed love affair between two freedom fighters. The emerging impression from this all is that the outcast and marginalized India is in fact the real India and if Indians were only able to embrace rather than ostracize it, their country would be a much better place. If not, then rather than revolution, the novel suggests internal secession, the making of a separate utopia of the dispossessed. In a world of so much mealy-mouthed middle-of-the-road-ism, I appreciate Roy’s radical vision.

Pachinko, Min Jin Lee (Grand Central Publishing)

Pachinko and Roy’s Ministry are a study in contrasts. They’re both long. Apart from that, one is messy, the other tidy, one exuberant, the other poised and well-behaved, one anarchic, the other persistent, sturdy. Both are ambitious summations of a people, India on the one hand, Koreans in Japan on the other. One might say the styles mirror the cultures they portray, in the case of India, kaleidoscopic and multi-faceted, in the case of Pachinko, the resilience and perseverance of immigrants who first strive to survive and then, having survived, to incrementally improve their lives and the lives of their children through hard work and hustle, eventually prospering. While people of Korean background face discrimination and exclusion in Japan up to today, the immigrants of the novel are presented not as victims but as agents of their own destiny. The multi-generational epic begins in Korea in 1932 and ends in Japan in 1989. The character who ties almost everyone together is Sunja, pregnant at 16 to a Korean gangster, then married to a saintly Korean Christian who takes her to Japan where he is unjustly imprisoned and dies. She perseveres, doing all she can to raise her two boys. Women are front and center throughout the novel. They hold their families together and, in spite of prejudices against them working outside the home, become impressively resourceful small entrepreneurs. And, at the end of the day, whereas Ministryis about families and love relationships broken by bigotry and persecution and how the individuals who emerge from that history make alternative families of their own, this is a novel about holding the family together, as a value in its own right, at all costs, however much it suffers from and is injured by the pressures of poverty, dislocation and Koreans’ outsider status in Japan. A straight-ahead narrative in the nineteenth-century mold, about immigrants’ rights, women’s rights, freedom of religion, children’s rights, racism and discrimination. An excellent interview with Min Jin Lee.

In the Darkroom, Susan Faludi (Metropolitan, 2016)

Renowned feminist writer reconnects with estranged 76-year-old father who is now a woman… and a Holocaust survivor from Hungary who became a successful photographer in New York (thus the pun of the title) and physically abused the feminist writer’s mother before divorcing. In her old age, she returns to the Hungary that killed her family. And, oh yes, the father has political views one might not expect from a transgender Holocaust survivor (for example, she supports Hungary’s right-wing government). The father has reconnected with the daughter because she wants her to write her story. The daughter starts out with a grievance but ends up with a sympathetic and honest portrait of her father in all her messy, self-contradictory complexity. About gender, LBGT and women’s rights, anti-semitism and the Holocaust, and all the different things a wo/man with a herstory like his had to do to survive. Brilliantly written too.

Originally out in Australia in 2015 and published in the US late last year, Dragons focuses on people dispossessed of their homes and land in Guangzhou, southern China. The come from an “urban village”, basically a village that’s been swallowed up by the expansion of a city but retains administrative and jurisdictional distinction which in theory should give it some local autonomy but in fact makes it all the more exposed to the depredations of greedy, corrupt developers and politicians working in cahoots. A phenomenon throughout China, urban villages tend to be refuges for the huge numbers of rural migrants who are legally discriminated against in cities. Urban villagers are on the front lines of the massively corrupt operations of government officials and developers to clear old areas in order to make way for gleaming, extremely profitable new towers. Theirs is a story of dispossession and injustice. It puts paid to Communist Party propaganda about how China’s rapid economic growth has improved the economic, social and cultural rights of its people; in fact, one could argue just the opposite has occurred because China has no effective legal system to protect the weak. And prosperity does not equal rights. A large part of the story of China’s economic growth is the story of relatively few powerful and well-connected people exploiting peasants and the urban poor to capture most of the benefits, creating a grossly unequal society. Bandurski befriends the urban villagers whose land and houses are taken away and, remarkably, also explores the networks of the officials and companies that steal from them. I regard post-Mao China as a kind of mafia state and this book certainly buttresses that view, but Bandurski’s perspective is judicious and measured, reminding of that of Nick Holdstock in his book on the Uighurs, China’s Forgotten People. Both are essential reading for understanding contemporary China through the eyes of ordinary people, especially those whose rights are abused, and their numbers are not small.

Like Shehadeh’s other books, this one is deeply moral, melancholic, and sensitive as well as stubbornly optimistic. If only Shehadeh’s humane sanity could prevail in this, the 50th year of occupation. The book’s backbone is Shehadeh’s decades-long, on-again-off-again friendship with Henry, a free-thinking, liberal Israeli. The friendship symbolizes the relationship between Palestine and Israel. Even the Israelis with the best of intentions cannot help but be complicit in injustice, as the foundations of their lives are based on the dispossession of the Palestinians. Shehadeh struggles to come to terms with Henry’s refusal to engage with the Palestinian struggle. He is alternately disheartened and resentful, and sometimes blames himself for being unfair to Henry. Along with the story of the friendship, Shehadeh reviews key events the two have lived through down through the years, the first intifada, the Oslo accords, the second intifada, to show how the situation has evolved, or actually, regressed. Not as great or original as the must-read Palestinian Walks, but Shehadeh’s deeply moral voice is always a welcome tonic for our times.

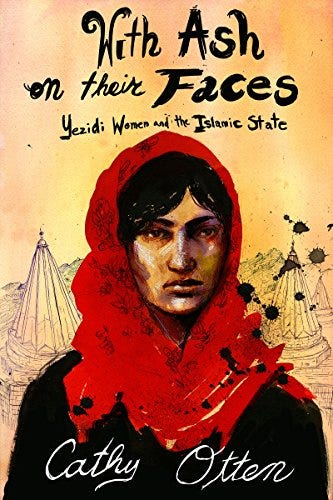

With Ash on Their Faces: Yezidi Women and the Islamic State, Cathy Otten(OR Books)

About if not full-on genocide then most certainly genocidal acts and crimes against humanity committed by IS and its local allies against the Yezidis, a minority ethnic group in Iraq with a long history of suffering oppression. While eventually focusing on IS’ enslavement of Yezidi women, the book also tells the story of how IS came to invade Yezidi lands. It examines the Yezidis’ relationship to Iraqi Kurdistan and the various Kurdish military groups which were supposed to protect them, as well as the issue of whether or not Yazidis can be considered Kurds (some think of themselves as Kurds, others do not). The author was already living in Iraqi Kurdistan at the time of the invasion and therefore well placed to tell the story. The fact that she is a woman must have also made it easier to interview the Yezidi women who have emerged from slavery and whose stories are the focus of the second part of the book. An estimated 6,383 Yezidis have been enslaved, with 2,590 escaping by mid-2016 and another 3,793 still in captivity. An estimated 3,000 have been killed (surely an underestimate), out of an overall population of several hundred thousand, most in Iraq’s Nineveh province. This easily qualifies as one of the most depressing books of the year, but even amidst the human depravity, there are grounds for optimism: Against Yezidi tradition, the women who escaped slavery have been accepted back into their communities under the guidance of the paramount Yezidi religious leader, and in spite of their unimaginable suffering and the obvious associated trauma, many women are outspoken, angry, defiant, and determined to lead the rest of their lives. An excerpt from the book.

The Far Away Brothers: Two Young Migrants and the Making of an American Life, Lauren Markham (Crown)

The title refers to 17-year-old twins from El Salvador who enter the United States as unaccompanied minors, primarily to escape what appears to be a death threat against one of them. The background of the story is the pervasive and epidemic gang violence in El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala which has caused a spike in arrivals of unaccompanied minors to the U.S. in recent years. The author met the twins through her social work at an Oakland, California high school for recent immigrants with relatively poor English. The twins are escaping definite danger, but their reasons don’t really fit established international or national criteria for asylum which put an emphasis on persecution, generally political in nature or having to do with the identity of the victim, for example, coming from a minority group. Markham goes to El Salvador to tell the story of the brothers’ family and also follows the twins after their arrival in the US as they try to procure leave to stay. The story shows just how complex their lives are and how many push factors exist. The twins come across as pretty typical teenagers, also in the sense that they make their fair share of questionable decisions that appear to run counter to their interests; the difference in their case is that they have much less margin for error. Markham’s narrative is always sympathetic not only to their plight but to their reasoning and makes us see that what may appear bad decisions have a logic that is not only understandable but, if I were in their position and from their background, I may very well have made too.

Rebel Mother: My Childhood Chasing the Revolution, Peter Andreas(Simon & Schuster)

Not sure it can be considered a human rights book, even though there’s plenty in it about children’s and women’s rights, not to mention the myriad ways in which rights were abused as a result of Cold War political violence in Latin America, like the overthrow of the democratically elected Chilean government, which features here. But I’m including it because it struck a chord: Andreas’ mother left his father and their typically middle-class life in Detroit and spirited Peter away, first to Berkeley, then to Chile, and after the Pinochet coup of 1973, to Peru, before returning to the US, and, after losing custody of Peter to his father, kidnapping him, returning to Peru, and then back to the US again. All in the name of her revolutionary ideals. Not only is the memoir a moving account of a profound relationship between a mother (who died in 2004) and son but also of a woman who rebelled from just about everything in her upbringing and society in search of justice and a better world. It can be easy to look back on revolutionaries of a previous era and see the errors in their thinking, and reading such accounts makes me reflect on my own political beliefs and wonder what will seem misguided a decade or three from now. Andreas’ mother partook of what I consider to be some of the delusions of traditional leftist thinking, perhaps foremost the idea that violence was justified and would get them somewhere. Andreas himself ends up a professor of political science at an Ivy League university, disavowing his mother’s radical politics and apparently taking a fairly mainstream liberal path. Missing from this account is his political reckoning with his mother’s views. That is something I would like to see, as it goes to one of the root questions of our time: between revolution, progressivism, and liberalism, which best realizes rights and leads to a better society?

This is a big oral history told by the British musicians and activists in the forefront of the eponymous movements that followed one another in quick succession from the late 1970s through the mid-1980s. It shows what a powerful force cultural activism can be for positive social and political change. Out of punk, ska, reggae and related genres grew a culture of resistance, to racism, to Thatcher, to neoliberal economic policies, and eventually to South African apartheid. It all started as a reaction to Eric Clapton’s drunken racist tirade at a concert in Birmingham in 1976. The book brings these years alive as a period of ferment, struggle and fun, as well as a zenith of positive youth culture, and goes into great detail regarding the tactics and strategies employed and how these were thrashed out by the musicians and activists involved. The author, Rachel, somehow managed to get almost all of the main actors to talk, and talk they do, at length and with heart. Reading it, I remembered how important music, rebel music, was in inspiring me to fight for human rights. And you can make an amazing soundtrack to accompany it.

The authors set out to raise $40,000 to publish the book and ended up raising over $1 million, making this the most highly funded original book in the history of crowdfunding. It tapped into the tenor of the times, countering the tendency of much of children’s (and adult, for that matter) literature to perpetuate gender stereotypes. It sends a message, especially to girls, that there are a lot of amazing women around the world and that girls should strive to be whoever and whatever they want to be. Each two-page spread features a single woman, with a portrait on one page and a bio on the other. One of the great strengths of the collection is its diversity, with a truly global perspective and an array of different vocations and endeavors. Many of the women are recognized worldwide, but as I read the book to my five-year-old, I came across more than a few for the first time myself. The second volume has just come out.

Rad Women Worldwide, Kate Schatz (Ten Speed Press)

Another very worthy book along the same lines is Rad Women Worldwide: Artists and Athletes, Pirates and Punks, and Other Revolutionaries Who Shaped History, by Kate Schatz and Miriam Klein Stahl(Ten Speed Press, 2016). It’s a follow-up to 2015’s Rad American Women A-Z, and it’s geared toward slightly older readers than Good Night Stories. It’s perhaps a bit punchier, feistier and subtly non-conformist, with profiles of people like Poly Styrene. There’s a wide array of books these days to counter gender stereotypes and promote girl’s and women’s rights, something for which this princess-detesting parent of a young girl is very grateful.

The best recommendation of this book is that my five-year-old was so inspired by it that she requested that, rather than presents, guests at her birthday party donate to organizations that help get more girls in school. She’s also proposing to her own school that it hold a Malala Day fundraiser. For a fuller story, Malala’s autobiography, I am Malala, is a better bet, but for younger readers, this is simple but not simplified, with beautiful illustrations, and at the back of the book, extensive additional information about Malala and the causes and issues to which she’s related.

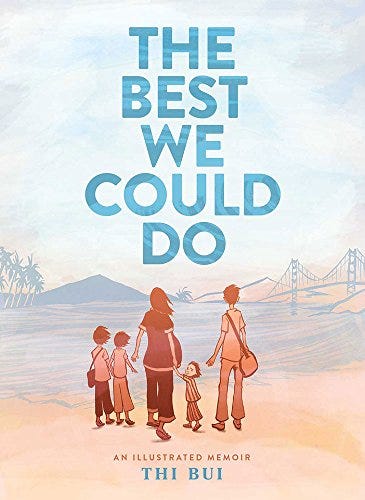

The Best We Could Do: An Illustrated Memoir, Thi Bui (Abrams ComicArts)

Called an “illustrated memoir”, this visually beautiful book is a pleasure to read. It tells the story of Thi Bui’s family. Her Vietnamese parents were married just as the war was heating up. In 1978, they, an infant Thi and three siblings escaped Vietnam on a boat to Malaysia. From there, they immigrated to the U.S., settling eventually in California. The story opens with Thi Bui giving birth to her first child, causing her to reflect on her parents’ story, how she learned about it, and how it affected her growing up and into adulthood. Her parents were traumatized by their direct experiences of Vietnam’s violent political history, and while Thi Bui was too young to experience that herself, she inherited the anxiety and fear associated with the trauma. It reminds of Nam Le’s story, “Love and Honor and Pity and Pride and Compassion and Sacrifice”, both about the problematic parent-child relationships of Vietnamese refugees. Such stories are part of a much-needed process in the U.S. where, up to now, most accounts of what is called the Vietnam War are told from the point of view of Americans. The more voices that emerge showing a Vietnamese perspective, the better. In this sense, this book plays a role similar to Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer.

Other Russias, Victoria Lomasko, translated by Thomas Campbell (n+1 books)

Victoria Lomasko calls her work “graphic reportage” at the crossroads of journalism and human rights activism. This is a collection of her drawings from 2008 to 2016. It’s divided into two parts, “Invisible” and “Angry”. “Invisible” is about the marginalized of Russian society, single women in dying rural villages, boys in juvenile detention, slaves, sex workers. “Angry”, as Lomasko puts it, “chronicles people’s attempts to come together and take back their voice and rights from the state”, with drawings of the 2012 Moscow protests, Pussy Riot, the LGBT community’s fight against the introduction of new homophobic laws, and the struggles of grassroots groups far and wide. The title of the collection comes from the idea that outside of what usually appears in the media, there are many other Russias, and these are what Lomasko sees as the true heart of the country.

March: Book 3, John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, Nate Powell (Top Shelf, 2016)

This is the third and last book in a trilogy that began in 2013. The whole trilogy is set in the early morning lead-up to Obama’s inauguration in 2009, which is depicted as a culminating victory of the Civil Rights Movement decades after its heyday. That morning at his office, Lewis is surprised by two young visitors and goes on to tell the boys the story of his life. The retrospection is effective, especially at certain points as, when, for example, he notes he’s the only person who spoke at the March on Washington in 1963 who’s still alive today. Lewis already has an excellent autobiography, Walking with the Wind, and if you’re looking for detailed information, that is a better place to go, but the graphic memoir is accessible and told in a very down-to-earth way that can appeal to people of many ages. To my surprise, my six-year-old loved it and was struck by many details, for example that Lewis learned to read the Bible at the age of five and recited it while preaching to his beloved chickens which the family had given him the responsibility of looking after, or that a thousand children were arrested on the first day of the 1963 children’s march in Birmingham. The three books are best as a package and now can be bought as a box set, but they can be read individually too. This third focuses on the Freedom Vote, Mississippi Freedom Summer, the attempt to get a multi-racial delegation to represent Mississippi at the Democratic national convention. It builds to the climax of the Selma march. Those of us striving for the fulfillment of rights often feel the wheels of history turn all too slowly and sometimes appear to be going backwards. Especially at this moment, there’s no room for complacency in regard to equality and race in the U.S. Nevertheless, the impression with which one emerges from this tale is just how stunningly rapidly the U.S. has changed for the better in a matter of decades in regard to improved rights for ethnic minorities, women, people of various sexual orientations and identities, and people with disabilities. Seen from that perspective, the U.S. is not only a country with a legacy of gross injustice in the midst of political crisis but also a place of hope.

The main difference between this and the first book in the series is that whereas the story of the first followed Riad’s parents from France to Libya and Syria, this second is set entirely in the home village of Riad’s father in Syria. Otherwise, it continues many of the themes of the first, namely, gratuitous violence, patriarchy, and political oppression. As with the first, the thing the book does so well is to show how intricately related these are, as to be inseparable, and as such, it is a study of dictatorship at both national and familial levels. To understate the matter, the village does not appear a very appealing place. Riad and his classmates are routinely beaten by their schoolteacher who appears to see her primary educational role as instilling loyalty to the Assad regime. Children in the village torture animals. There is an honor killing. It’s not such a leap to make a connection between this and the Syrian civil war of today. The structural violence pervasive on all levels of society here, from the family to the dictatorship — violence as a culture, a practice, a habit is extraordinarily difficult to unlearn.

About acts of genocide that occurred in Daoxian County, Hunan Province, China during the Cultural Revolution in 1967, fifty years ago this year, this books is a labor of love, or perhaps, given the subject matter, “love” is not the right word — something more like a deep sense of social and moral responsibility. Tan says he would have preferred not to have been the one to bring this to the world’s attention, but when no one else did, he felt he had to. Meticulously documented (the Chinese original is twice the length of the English translation) and originally published in Chinese in Hong Kong because it was impossible to publish it on the mainland where the Communist Party, responsible for the Cultural Revolution, is still in power and entirely unaccountable for this and many other similar atrocities and gross injustices. It has a vested interest in hiding the history of China under its rule from the Chinese people. One feels, in reading Tan’s account, that Daxian County was not an outlier in its excesses, even if its particularities may be unique, and that there are many other stories of gross injustice and genocide to be uncovered. I cited Tan in the preface to my own book, on the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement, to explain why I motivated to write it: “Chinese history, especially modern history, is full of erasures and falsifications and portions inked out or obscured by mold. Discussion, reflection, or even recollection of appalling incidents of violence has repeatedly been made taboo, while the vacuum is filled with monstrous lies and the brainwashing of one generation after another. Each of these junctures has sealed the tragic fate of China’s people. Once a group or even a generation of the duped and misled regains consciousness through personal experience, the creators of lies can easily find a new group of victims and of the credulous in the next generation. Truth is a tonic for the conscience of the nation. There is nothing more toxic to a society than the lies imposed by those above on those below. We must treat all bogus truths, bogus history, bogus incidents, and bogus models as we treat fake merchandise and tainted food, relegating them to the rubbish heap of history. Only then will our people truly have hope.” Ian Johnson has an insightful review of The Killing Wind as well as a striking interview with Tan.

Written in secret (even from his own brother) in a cave home belonging to his mother in Shaanxi while under house arrest and cut off from the rest of the world by the authorities after his “release” from years of detention of various kinds, most of which of dubious legality if not complete and blatant illegality, Gao’s words have come a long way by the time they reach your eyes. During the multiple detentions, Gao, one of China’s pioneering rights lawyers, endured torture and various forms of mistreatment which damaged his health as well as his mental state. About the latter, he does not go into detail but refers to various suicide attempts. The manuscript of the book was smuggled out of China and, like The Killing Wind (see above), originally published in Chinese in Hong Kong. Some of the media coverage of Gao’s account has focused on wackier aspects, such as his claims that he had a vision that the Communist Party would fall from power in 2017 and that various entities of the security apparatus are haunted by ghosts, and not just metaphorical ones either. But in spite of these, I was struck by just how cogent Gao’s account is. It is a piercingly incisive description of the Kafkaesque vagaries and cruelties of the Chinese legal, detention, prison and military systems. Gao’s combination of extraordinary bravery, legal expertise and knowledge of the massive systems of incarceration in China make for one of the best recent accounts of imprisonment by one of the most repressive regimes in the world. In the meantime, his ordeal is far from over. On 13 August, he was presumed to have escaped from his extra-legal house arrest, only to have been apprehended three weeks later, but it is now unclear whether he is being detained and, if so, by which Chinese enforcement agency. In terms of human rights law, he has been once again forcibly disappeared. His story is a parable of China today. An excerpt

OK, worst cover of the year, but as they say, don’t judge a book by its. From his role in the 2003 abolition of the detested custody and repatriation system, Xu has been in the forefront of many initiatives to incrementally push China in the direction of what he calls constitutionalism and transparency, foremost being the Open Constitution Initiative and the New Citizens Movement, both of which were crushed by the regime. His show trial in 2014 and four-year imprisonment for “gathering crowds to disrupt public order” marked the end of the so-called “rights defense” era during which the strategy was to slowly strengthen civil society in the belief that the political system could be slowly improved. Now this avenue has largely been cut off by the regime’s crackdown not only on lawyers like Xu but on all forms of independent civil society. Xu can at times seem almost unbelievably earnest and optimistic about China’s future. If such a moderate person with such great dedication to and belief in rule of law is imprisoned, it shows just how little hope there is under the Communist Party. This book is composed of memoirs, going all the way back to his boyhood in poor rural Henan province, and diverse other writings by Xu which together form an overview of his life and career working in the public interest. Xu comes from a younger generation of rights lawyers than Gao Zhisheng (see above), and this book is a testament to what a sane, moral, right-minded, intelligent, well-meaning, passionate and truly patriotic Chinese person thinks and feels these days. His closing statement at his trial (which he was not allowed to read in full) gives a flavor of his game. In November, several months after his release from prison, Xu published this declaration, which shows that, contrary to prevailing sentiment, he’s as optimistic as ever. Andrew Nathan’s introduction can also be read here.

The most recent human rights treaty to enter into force is the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance in 2010. Rather than sign and ratify the treaty, less than a year later, in 2011, China was testing out a new form of enforced disappearance called Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location. After an anonymous online call went out for a Jasmine Revolution in China, inspired by the Arab Spring, the Communist Party rounded up hundreds, many of whom ended up forcibly disappeared for a matter of weeks and months. A couple of years later, China formalized the procedure by “legalizing” it through revision of its Criminal Procedure Law. Since then, RSDL has become one of the state’s primary means of kidnapping rights advocates, usually lawyers and NGO workers, often on grounds that they are “endangering state security”. Once kidnapped, people under RSDL are held incommunicado at a secret location, often belonging to the police or military, entirely outside of any judicial process and without any rights or due process. Some of the people who tell their stories here — Wang Yu, Xie Yang — are well-known. Their cases received widespread international media coverage. But this is the first collection of their detailed accounts. All were tortured in custody (the one foreigner, Peter Dahlin, to a much lesser degree), and many suffer still as a result. Striking is that while beatings are frequent, and some can be severe, there is a pattern of what I call “plausibly deniable” mental and physical torture designed to leave no tell-tale signs. For example, Xie Yang was subjected to many days of nearly complete sleep deprivation coupled with the “dangling chair” and threats to kill both him and his family. As with Gao Zhisheng’s memoir (see above), reading this is like taking a direct glimpse at the cruelty and brutality that are the heart of Communist Party rule. As Caster points out in his excellent essay at the end of the book, the systematic practice of enforced disappearance in China is a crime against humanity under international law. Dedicated to Wang Quanzhang, who is still disappeared more than two years after first being abducted.

Published in 2010 and circulated underground in Tibet ever since, this book has just appeared in English. It’s considered one of the more important Tibetan texts composed in recent years, and trailblazing in its discussion of politics. In retaliation, the Chinese Communist Party imprisoned Shokdung (also transliterated Shogdung) for six months and banned the book. The book represents a kind of epiphany for Shokdung, who previous to it was best known for criticizing what he regarded as the excessive influence of religion on Tibetans, believing that it was a major impediment to their advancement as a people. His arguments were sometimes used by regime supporters to justify its long-standing attacks on Tibetan Buddhism, and he was criticized by Tibetans for playing into their oppressors’ hands. But when Shokdung witnessed the Tibetan uprising of 2008, he was so impressed that he admitted he was all wrong: Tibetans were more than intellectually and psychologically prepared to take their fate into their own hands. This book is his coming-to-terms with that uprising and its implications. Reading it is like overhearing a conversation, since the text is largely directed at Tibetans, and its purpose is firstly to celebrate the 2008 Tibetan uprising as a truly wonderful, even miraculous occurrence, and secondly, to introduce the concepts of nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience to Tibetans. This latter seems weirdly superfluous as it was Tibetans putting them into practice in 2008 who “taught” Shokdung about them, but his point is that it would be useful to Tibetans to know more about the history and conceptual tenets of nonviolent struggle elsewhere in the world and as an intellectual, he wishes to introduce the concepts of nonviolent resistance into the Tibetan vocabulary. The Communist Party keeps Tibet such a closed society that it’s not that often that strong voices make it out. Hurst is to be applauded for bringing Shokdung’s to an international audience.

October: The Story of the Russian Revolution, China Mieville (Verso)

It seems only appropriate on the one-hundredth anniversary of the Russian revolution to have a book about it on the list. As many have commented, the number of books about the revolution is, by one estimate, 20,000, 6,000 of those in English. And of all those books, why this? Simply put, because it’s well told and accessible to someone like myself who’s far from an expert on the revolution. In fact, most everything in this book except the broad outlines of the narrative was news to me. Miéville is best known as a writer of what he calls “weird fiction” (and others often refer to as fantasy fiction), and he brings his storytelling skills to bear on the task of putting a coherent story together of many months of political chaos and intrigue and dozens of splinter groups of every political persuasion. And why on this list of human rights books? Because the Bolsheviks were fighting for the rights (if you want to call them that, though the term can seem anachronistic since it wasn’t really part of the Bolshevik vocabulary) of particular classes and, in so doing, erected one of the worst rights-abusing regimes in modern history. How did that happen? The story begins with its origins, years before Stalinist terror and gulags, and here’s where Miéville may disagree with me. In this sense, I may be reading this book against itself. Miéville characterizes Stalin as perverting the revolution, but all of the Stalinist tendencies were there from the start, in particular, the idea that violence was always justified as a means to attain and maintain power. I’ve thought of and recommended this book often this year, a year in which I have gotten in more arguments with people I share political beliefs with than in any other I can remember about the efficacy of violence as a means to resist tyranny and get political power. I’m firmly opposed to it on moral and strategic grounds and believe the case of the Russian revolution lends weight to my arguments. The response is, Without violence, how else would things have changed? You need very specific conditions for nonviolence to work, such as when racial majorities far outnumber ruling minorities (India, South Africa). A definite minority in the wider Russia at the time, or a vanguard to use their own terms, the Bolsheviks needed violence to gain power, then defeat the counter-revolutionaries and perceived enemies within. Before long, everyone became an enemy, even those within their own ranks. And well, we know how it all ended. Here I find myself agreeing with people on the right-wing of the political spectrum whose views I otherwise abhor: “The forced-labor camps, the one-party state … the prohibition of free and popular elections, the ban on internal party dissent: not one of them had to be invented by Stalin. … Not for nothing did Stalin call himself Lenin’s disciple.” I believe dictatorship and violence are always wrong. Does that make me naïve, doom me to ineffectuality? I wonder sometimes myself.

Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine, Anne Applebaum (Doubleday)

And here’s the perfect antidote to any tendency to romanticize the Russian revolution (along with Appelbaum’s equally superb Gulag). Red Famineshows the Holodomor, as it is known in Ukraine, was as much about repressing Ukrainian nationalism as it was a result of the massive downturn in food production caused by enforced collectivization of farmland. In other words, it was an intentionally inflicted famine. As Adam Hochschild puts it in his excellent review, “The planned starvation, the execution of the territory’s best artists and intellectuals, the destruction of churches and the crushing of traditional village culture terrified into silence any Ukrainians who wanted autonomy or independence. Then finally, 60 years later, what Stalin had feared happened virtually overnight, and Russia did lose Ukraine.” The Holodomor was a precursor to Mao’s Great Famine of 1958 to 1962. Peaking in 1933, it resulted in upwards of five million Soviet deaths, of which 3.9 million were Ukrainian. Estimates of Mao’s Great Famine fatalities range from 30 to 45 million. In both cases, the extent of the famines was well-known by the political leaders, who were either blithely indifferent or intended to inflict suffering. Red Famine should take its place along Frank Dikotter’s Mao’s Great Famine and Yang Jisheng’s Tombstone as histories of atrocities perpetrated by Communist dictatorships causing tens of millions of deaths. Applebaum sets the history in the context of Ukraine’s newfound independence, which perhaps can give hope to those of us who often can’t see how to overcome the worst.

On its fiftieth anniversary, more than two dozen mostly foreign writers confront the occupation in solidarity with the occupied. Their main purpose is to convey to the rest of the world the daily experience of living under occupation. Foreign writers are well placed to do this because they understand what the rest of the world doesn’t understand and therefore what needs to be communicated. In the introduction, editors Chabon and Waldman (who are Jewish) honestly tell of their years-long ambivalence about and avoidance of the issue and why they finally decided to confront it. There are some outstanding pieces. It’s no surprise that one of the best comes Rajah Shehadeh, a Palestinian himself (whose own book came out this year — see above), who writes about taxi drivers as the unsung heroes of the resistance, thereby illustrating how Israeli roads have turned the West Bank into a surreal labyrinth and cut it up into smaller and smaller cages. In “Prison Visit”, Dave Eggers focuses on just that, how living in Gaza is like being in a big prison. Most of the pieces focus on people the writers met, and the writers cover most areas of the West Bank, from the cities to the villages, as well as East Jerusalem. Royalties go to two excellent organizations, the Israeli anti-occupation NGO Breaking the Silence and the Palestinian Youth Against Settlements, reason enough to buy the book.

The same idea as Kingdom of Olives and Ashes (see above), a collection of pieces on Palestine by well-known mostly foreign writers, but here there are about 50 pieces, although generally shorter than those in the previous book, and This is Not a Border marks not just 50 years of occupation but also 10 years of the extraordinary Palestine Festival of Literature. Many of the pieces are based on the writers’ appearances at the festival. Its strength lies in its diversity, in its coverage of over a decade of the festival, and in the excellence of the writing. Some pieces like J.M. Coetzee’s very brief, “Draw your own conclusions” and Teju Cole’s “Cold Violence” have taken on lives of their own. Others, like Pankaj Mishra’s “India and Israel” and Mohamed Hanif’s “Pakistan/Palestine”, provide perspectives on the occupation from parts of the world from which Westerners at least may not be used to seeing it. Ghada Karmi’s books on Palestine are must-reads, and her piece here, “The City of David”, on an Israeli archaeological dig is also excellent. The Egyptian writers Ahdaf Soueif and Omar Robert Hamilton are mother and son and also co-founders of the festival. Hamilton’s novel, The City Always Wins, is also on this list.

One of the few books about Syria to appear in English written by a Syrian who directly experienced the revolution and war, and much else before that. Al-Haj Saleh was a political prisoner of the Assad regime for 16 years. After his release, he married another political prisoner. During the revolution and war, he lived, much of the time undercover, in Damascus, Douma and Raqqa before escaping to Istanbul. His wife remained in Douma, where on 9 December 2013, she was kidnapped together with renowned fellow human rights defender Razan Zeitouneh and two others, none of whom have been heard from since. This personal tragedy is referred to only in the introduction to the book. This book is composed of ten articles out of the 380 al-Haj Saleh wrote between 2011 to 2015. They trace the trajectory of the revolution from hope to war to despair. That is largely the narrative that’s appeared in the media, but the inside picture al-Haj Saleh provides of Syrian society gives much deeper insight. The book’s called The Impossible Revolution because even though the revolution was impossible, it occurred, but because it was so impossible, it did not succeed. The articles are highly intellectual, abstract and theoretical, written in a style that non-academic readers may not find immediately accessible. Perhaps their greatest value lies in their examination of the Assad dictatorship. Some have wanted more of the autobiographical out of al-Haj Saleh, and this is understandable for he has an extraordinary personal story to tell, which is at the same time all-too-representative of the tragedy of Syria under dictatorship, but al-Haj has written autobiographically of his time in prison (not yet translated into English) and one senses that his recent history is still too raw and painful for extensive treatment. (Recently, al-Haj Saleh published seven open letters to his disappeared Samira.) The book is highly critical of virtually all those implicated in the catastrophe, first and foremost the Assad regime, but also the various Islamist militias, as well as Hizbollah, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, Russia, China and the United States. It’s taken the sins and errors of omission and commission by many actors to make such a tragedy. Only the nonviolent revolutionaries and, to a lesser extent, the Free Syrian Army, come out looking good. Good interview

We Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from Syria, Wendy Pearlman (Custom House)

The point of this oral history is to allow Syrians to speak for themselves. It is based on interviews conducted with those who have fled the country in Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon, Germany, Sweden, Denmark and the U.S. Pearlman is a U.S. university professor who specializes in the Middle East and speaks Arabic. The book is organized chronologically, from background on Syrian history to Assad dictatorship to revolution to repression to the militarization of the rebellion to war to mass exodus. The introduction gives an excellent overview of these phases. Perhaps one of the clearest messages to arise from the many voices in the book is how abandoned Syrians feel by the rest of the world.

Affluence without Abundance: The Disappearing World of the Bushmen, James Suzman (Bloomsbury)

Is it a human rights book? It’s definitely neither pitched nor intended as such. Written by an anthropologist, Affluence without Abundance is a wide-ranging portrait of the Bushmen of southern Africa, one of the most prominent hunter-gatherer societies that has managed to survive up to now, although, judging by this book, it now seems to be in tatters. The reason I decided to include it on the list is because of its deep insights into a group of indigenous people as well as their terribly fraught relationships with other groups (the Afrikaans-speaking white farmers and the pastoralist Herrero people of Namibia — themselves victims of a genocide under German colonialism) and the state. The picture is not pretty. What emerges is that while on their own cultural terms, they are amazingly resourceful and have succeeded over millennia at living in a very harsh environment, they are so cut off from modern society that they haven’t the power to advocate well on their own behalf in terms that the dominant society will understand or accept as legitimate, and too often there isn’t anyone else in positions of power who is particularly interested in advocating on their behalf. So yes, this is the story of another group of indigenous people getting screwed. But beyond that, it goes so deeply into their culture and world and sets it in so many different contexts, that it conveys a deep appreciation of the value of that culture not only to itself, obviously, but to the wider world. The reference in the title is to the idea that the bushmen can be considered affluent even though they definitely do not possess abundance, indeed, their culture revolves around the objective of possessing as few things as possible, and Suzman makes reference to Keynes’ vision of a day when modern society would be so affluent, people wouldn’t have to work so much and would have great leisure to engage in more meaningful pursuits. But given the state of the bushmen today, the connection drawn hardly seems apropos — these people are getting whittled down to nothing, and in their current state, appear more dispossessed than affluent. The grim lesson, from that perspective, is that unless you have power amassed from incessant accumulation of wealth, you will be destroyed.

You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, Sherman Alexie (Little, Brown, and Company)

This is a deeply personal and alternately sad and humorous memoir circling around the death of the author’s mother and his relationship with her. Since his mother was a Native American and one of the last fluent speakers of the language of the Spokane Indians, and since she was not only a rape victim but also the product of a rape, and since the author had such a complex relationship with her, not least of all over matters of what it meant to be a Native American, the memoir is also about the post-genocide situation and identity of Native Americans suffering from high rates of poverty, alcoholism, suicide, unemployment and other diseases recognizably associated with genocide survival. And in this sense, it contributes to a growing body of literature on the subject. Just in the past two years, some amazing books have been published: The Other Slavery, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States and An American Genocide. This book is written in Alexie’s typically gregarious, colloquial and highly readable voice, and rather than being linear is deliberately circular, returning repeatedly to certain moments, feelings and ideas. It’s also full of poetry. Sometimes one might think it could have been better edited, but letting it all hang out is part of the point. It also reveals just how autobiographical Alexie’s Young Adult masterpiece, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian is, one of the books I recommend most frequently to teenagers.

Direct Action: Protest and the Reinvention of American Radicalism, L.A. Kauffman (Verso)

This book picks up where Clara Bingham’s oral history, Witness to a Revolution, left off, with the leftist and anti-war youth movement disheartened and fragmented at the start of the seventies. Indeed, it begins with the question, What happened to the American left after the sixties? Its starting point is the last major protest against the Vietnam War in Washington DC, May 1971 and goes all the way up to the protests against the police killing of Michael Brown in 2014. Its premise is that whereas there was some central focuses of the sixties, such as the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-war movement, the history of direct action since that time consists of a proliferation of movements, causes and political identities. The book focuses in particular on feminism, LGBT rights, the campaign for adequate medical treatment of people with HIV/AIDS, racial justice, environmentalism (in particular deep ecology and the climate justice movement), and anti-apartheid. Kauffman focuses on direct action because, she says, “It has… consistently served as a laboratory for political experimentation and innovation, and as an arena for grappling with many of the big challenges facing progressive movements…: how to win meaningful victories and sustain communities of resistance in a rightward-shifting political climate; how to build movements that don’t replicate the very power dynamics they seek to challenge…; how to create effective political alliances that respect the voice and autonomy of all partners; how to inspire vision, hope and action in hard times.” What I found most striking was that many of the movements depicted suffered many defeats and often appeared small and marginal, but on just about every issue on which they pushed, there has been marked improvement over the longer term. Of course, that’s not only down to direct action groups — indeed, most social and political progress comes from a variety of groups working on a similar cause in a variety of ways — , but so many of the radical concerns of previous decades have shifted to the mainstream, not least of all due to the efforts of these vanguards. Sometimes things do indeed need a hard push, though the people who make that push, with all of its attendant sacrifices and suffering, rarely get the credit they deserve.

No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age, Jane F. McAlevey (Oxford University Press)

McAlevey has a background as an organizer in the US labor movement. Over the past few years, she’s gotten her PhD and this book is the result of a period in which she’s had time to reflect. It essentially consists of case studies of labor activism from which she gleans conclusions and advice. The most interesting studies are of the Chicago teachers strike, the unionization of Smithfield slaughterhouse workers, and the methods of Make the Road New York, which focuses on recent immigrants doing low-wage work. The title refers to her basic message, which is conveyed very persuasively: If you want to succeed, you have to organize organize organize. She contrasts organizing with mobilizing. The latter means getting people to do something as part of a short-term campaign. The former means cultivating relationships, building communities, cultures, networks and support systems. It’s difficult but a necessary platform to struggle for objectives which will take time to acomplish. Many useful examples of this deep organizing are given. McAlevey believes much of the focus of activism in recent years has been on quick pay-offs and the tactics employed are meant to achieve that, but that kind of activism can be superficial. Anyone engaged in activism can learn a great deal from the book. Reading it, I had many aha! moments reflecting on the deficits of the movements in which I’ve been involved, and am employing the lessons to the struggle for democracy and autonomy in Hong Kong.

About enormously rich white men trying to undermine democracy. I can’t say that’s one of my favorite topics, and these rich white men are terribly uninteresting, but they are immensely powerful. To read this book is to know your enemy — it’s not often that great wealth is a friend of human rights and democracy. The role of big money in US politics, from increasingly obscured sources due to Supreme Court decisions like Citizens United, is one of the biggest threats to US democracy (along with gerrymandering and new laws intended to restrict voter rights). This is prodigious investigative journalism that has rightly won much acclaim. If anything, Trump’s victory might be regarded as encouraging insofar as he basically bumbled into it, and the people profiled in this book, like the Kochs, were initially opposed to Trump, but while they haven’t yet installed their man in the White House, they’ve captured the Republican Party and done much to create a political climate that makes a phenomenon like Trump possible.

On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, Timothy Snyder (Tim Duggan Books)

This short book started as a Facebook post not long after Trump won. It came out shortly after his inauguration and was criticized by some for being alarmist, since many of its lessons are borrowed from Snyder’s study of Nazi and Communist totalitarianism. But Snyder’s point is exactly that we mustn’t be complacent, we must be vigilant. The book is largely focused on giving advice about what it means to live as a free, responsible citizen in a democracy and what is needed to defend democracy from its enemies. Some of the lessons are more incisive than others. Two of my favorites are “Do not obey in advance” and “Defend institutions”. From the first, I got the concept of “anticipatory obedience” which I’ve found to have great explanatory power in a variety of political situations.

Wesley Lowery is a journalist who covered the multiple killings of black people by police officers in the US as well as protests against them pretty much from the time of Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson onward. The value of this account is two-fold: first, it seems to occur almost in real time, so recent and raw is the history it traces, and second, because he had a good relationship with many of the most prominent activists in the movement, we see how they got involved, what they thought, and how they devised tactics and strategies to push their message to the fore of the national debate for a period of time. These activists are very much of a younger generation that is not the Civil Rights Movement nor the black political establishment that emerged in many cities across the US in that movement’s aftermath. The story goes from Ferguson to Cleveland to North Charleston to Baltimore to Charleston and back to Ferguson a year later. Issues and movements can flame up and out so quickly: As Lowery notes in the afterword, more people were killed by police in the US in 2016 than 2015. The issues Black Lives Matter addressed were hardly visible in US elections in 2016. I suspect the impact of BLM will be felt in the longer term, depending on what those who were mobilized and whose consciousness was raised go on to do in areas of racial justice, police violence and beyond. Trump is everything BLM opposed, but I suspect that the culture that BLM and similar movements have generated will come out on top in the end. The extent to which it does depends on whether or not the movement is able to broaden out to address structural issues related to black liberation such as mass incarceration, perpetual housing segregation and black unemployment, as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor argues in her 2016 book, From#BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (which should have been on my list last year).

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy, Ta-Nehisi Coates (One World)

This book is much better than even the positive reviews have allowed. I didn’t anticipate it with that much enthusiasm because I thought it would be little more than a collection of Coates’ essays previously published in The Atlantic. That is, indeed, partly what it is, but not only do most of these eight essays stand the test of time, the best rank among the most insightful thinking in the U.S. on racism and many related issues in recent years. These include “The Case for Reparations”, especially the section on systematic housing discrimination and its effects on black people, and “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration”, which brings home the effects on families of US policies which have lead to the highest rate of incarceration in the world. Both are classics. The most recent essay, “My President Was Black”, is also a gem. But I’d already read those; what made the book for me is its structure: Those previously written essays with what Coates calls extended blogs, in which he reflects on his own life at the time of each essay’s writing as well as his thoughts about the meaning of Obama. His style in these prefaces hearkens back to what I think is his best book yet, The Beautiful Struggle, about his youth and relationship with his father. For example, prefacing the first essay is his memory of having lost his third job in eight years and having to attend mandatory job training classes. Coates is good at connecting personal experience with political thought and using each to advance and illuminate the other. Before Obama was elected, Coates thought there was no chance America would choose a black president. But it did, and Coates had to reassess. He then went through a period of relative optimism, and has since crashed back down to earth. As he reflects, “In those days I imagined racism as a tumor that could be isolated and removed from the body of America, not as a pervasive system both native and essential to that body.” Now he tends toward the latter view. Many have commented on his supposed pessimism. I’m more optimistic than Coates. I think Trump is White Supremacy’s last gasp. The only question is how much damage and destruction it will cause before it’s vanquished. Demographics work in favor of a gradual, two-steps-forward-one-step-back shift away from White Supremacy: the country’s becoming ever less white and will continue to do so. This won’t happen overnight — I emphasize gradual — but it will occur. In these days, not just in the U.S., there is a need for rationally angry writing, for writing that pulls no punches, and that is one reason Coates is to be treasured.

“To enact reparations would mean not simply an outlay of money but also a deep reconsideration of America’s own autobiography. The implications could not be confined to the presumably narrow realm of ‘race’. What would it mean for American foreign policy, so often rooted in its image as the oldest enlightened republic and pioneer of the free world, to forthrightly note that that freedom and enlightenment were only made possible through a plunder that stretched from the country’s prehistory up into living memory? For Americans, the hardest part of paying reparations would not be the outlay of money. It would be acknowledging that their most cherished myth was not real.”

Age of Anger: A History of the Present, Pankaj Mishra (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)