By the Labour Party’s Leo Tang Kin Wa

The new Secretary for Labour and Welfare rushed to visit Cambodia soon after he took office. Against a backdrop of “One Belt One Road”, the Hong Kong and Cambodian governments signed a trade agreement – one of the terms of which was that Hong Kong would allow Cambodia to “sell people” to Hong Kong as domestic workers.

The new secretary reiterated that according to Hong Kong’s population projections, Hong Kong will have more than 600,000 foreign domestic workers in the future – therefore, more “sending countries” of migrant workers are needed to increase the “supply”.

At the same time, the government put out feelers about the implementation of a “pilot scheme” to fund the hiring of foreign domestic workers by the elderly. All of these facts show that the current government intends to shift the responsibility for taking care of the old and disabled to their families, and build up a care system based on exploitation.

In the film Mad World, Tung – played by Shawn Yue – while recalling his time taking care of his dying mother, describes a foreign domestic worker who does not appear in the film. She was burnt with hot water while she was taking care of his mother, played by Elaine Jin.

The son went home and had the domestic worker’s agency deal with the incident. The domestic worker, who is never seen onscreen, aptly shows the situation of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong’s family care system – in between being seen and unseen.

Without our being aware of it, invisible foreign domestic workers are “embedded” in the care system of Hong Kong. Their role is not expressly prescribed, but it has become the unspoken consensus of our society.

The caregivers and the cared for in captivity

For many Hongkongers, when someone needs to be taken care of at home, whether or not they are ill, almost the only option is to hire a foreign domestic worker. Due to the lack of public services, it is inevitable that foreign domestic workers fill in the gap.

These workers are the shadows of the handicapped, the mentally ill, the old, and the young of a family – staying at home to take care of them, accompanying them to schools or to hospitals for follow-ups, assisting them with therapy, helping to wash the paralysed – providing all sorts of care round-the-clock.

If we say that Mad World unveils the inadequacy of Hong Kong’s care system for mental patients, that the system has yet to collapse is precisely because of the sweat and toil of over 300,000 foreign domestic workers.

Hiring a domestic worker to take care of the old, the young, and the ill in the family seems to be the individual decision of the families, but in fact it is a system quietly recognised by the government.

I handled a case which at first seemed to be a labour dispute over the long service payment of an Indonesian worker, but – in the end – it revealed the blind spot of the Social Welfare Department’s policies.

This Indonesian sister, named Ah Lei, worked for a wholly paralysed woman named Ms Fung for 7 years, until Ms Fung passed away. Ah Lei came to the union for help, saying that she could not receive her long service payment.

One might wonder – how could Ms Fung, paralysed and living off of CSSA, afford to hire a foreign domestic worker? We later found out that there are “special grants for care” of around HK$4,000 provided by the CSSA, allowing recipients to hire a foreign domestic worker.

After the passing of Ms Fung, this sum of money became an “inheritance,” which can only be collected after long procedures. Though, in the end, the Social Welfare Department made special arrangements to hand this sum of money to Ah Lei directly, the case revealed the cruelty of the system.

A wholly paralysed person is not even able to vote; how can she take on the responsibilities of an employer? For our government, the 24-7 service of taking care of Ms Fung is only worth HK$4,000.

This case reminded me of another news story: an autistic son was stabbed over 100 times, to his death, by his mentally ill father. The defence submitted over 700 letters in mitigation of this domestic tragedy.

Few of the public noticed one detail – not long before the incident took place, this family used to employ a foreign domestic worker, but she could not handle the stress and resigned, which made the father desperate.

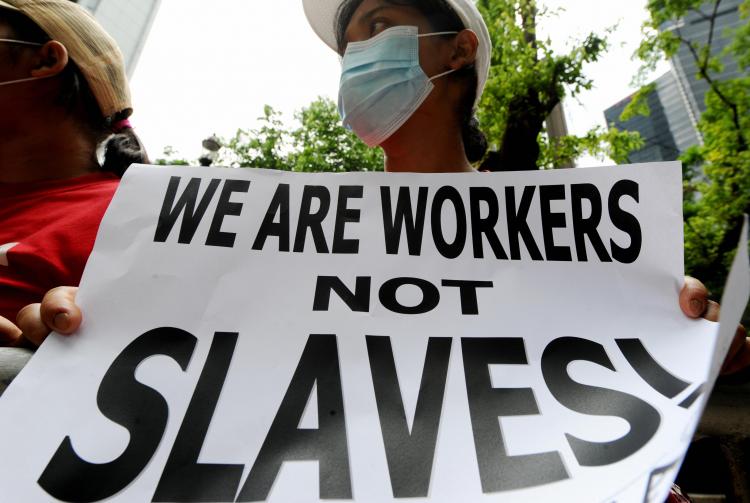

The pressure on this domestic worker in employment would not be less than that on the father. Many foreign domestic workers who take care of the paralysed or the old may not even have a holiday in years. They are held in captivity with the person they care for.

A subsidy scheme under the guise of community care

The government’s public spending has shrunk to where it can shrink no more. Hongkongers are used to getting no return on the taxes they pay. They only long to “get their money back” in the short-term and hire a foreign domestic worker to “take care of their own business.”

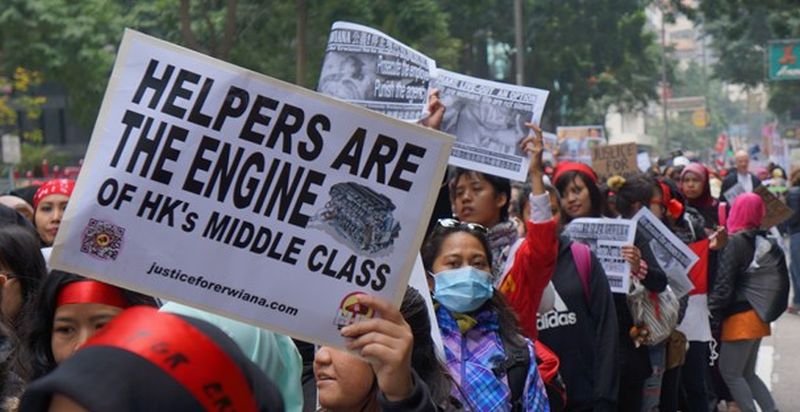

The media depicts the matter as “one more choice” from a consumer’s angle. In the name of “community care”, the government’s “subsidy scheme” remains intact under camouflage. The role of the government is to keep suppressing foreign domestic workers’ wages at a low level, and turn these Southeast Asian women into “social welfare vouchers”.

No one asks about workers’ rights

But starting schemes to allow more foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong and subsidise the elderly to hire domestic workers, before tackling the various problems these women face, can only cause more problems.

Do the Cambodian newcomers have sufficient employment, and rights-based support? Currently, there are over 350,000 foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong. They face unscrupulous agencies who constantly break the law in ever-shifting ways.

Cambodian domestic workers lack the support of a rights network, so how can they seek justice if they are are unlucky enough to encounter an unscrupulous agency or a bad employer? Can the design of public housing for the elderly who live alone provide sufficient space and privacy for the living area of a domestic worker?

How can an elderly person ensure their foreign domestic worker is fed and well-rested, and be a good employer, when he or she is the one who needs long-term care and a subsidy to hire a foreign domestic worker? None of these questions are raised, of course.

The government treats the welfare of the old and the disabled as a burden. Therefore, we have a care policy based on exploitation.

Translated by Isabel Yin Tsz Chang.