It’s no secret that the early settlers of Hong Kong Island in the 1840s were not drawn by the beautiful landscape and environment. Far from it. Early chroniclers spoke of the place as ‘precipitous and uninviting’, clouded in ‘noxious vapours’, where the ‘fetid air’ could be fatal.

No, what drew in the ships of foreign traders was the deep-sea harbour, nestling right there, off the entrance to the Pearl River up which lay the Chinese market for world goods. Land was necessary for warehouses and trading offices but what mattered was the harbour and what drove it was shipping.

But how did that actually happen? Was it all thanks to some wily Chinese junk-builders and family clans of seamen ready to travel the seven seas now that trade had been liberalised, up and down the China Coast?

Not exactly. There were some junks handling South East Asian trade out of Canton, competing with Portuguese ships out of Macau for the cargo business. But there were few Chinese seamen at the time who had much experience of sailing far beyond Chinese coastal waters. Virtually none of them knew anything about non-junk rigging; they refused to climb the mast as required on western-rigged ships.

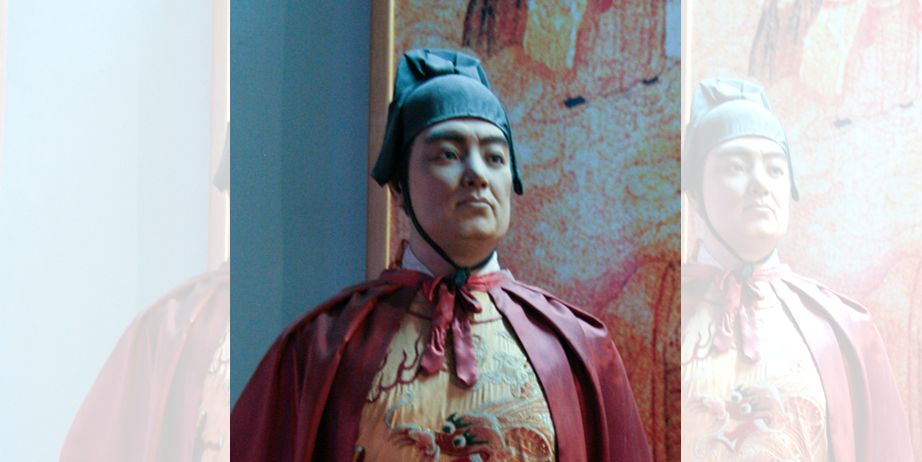

We’ve all heard of the famous eunuch Admiral Zheng He who, incredibly, sailed seven great journeys in his ‘Treasure Ships’, taking Chinese seafaring as far as Madagascar off the southeast east coast of Africa.

But that was in the early 1400s; we’re talking about the 1840s. The time in-between, as far better historians of China can tell you, was not a time of outreach by the Chinese empire. On the contrary, people seeking to go abroad were punished and those who left were spurned. There were several hundred years in here where it was simply not a good look to be seen itching to go abroad.

By contrast, the age-old habits of seafaring through the tricky seas of what we now call South East Asia had continued unabated for centuries. No-one in South or South East Asia had waited for the Europeans to come along and point out the monsoon.

On the contrary, shipping across the Indian Ocean, through the Malay Seas and up as far as Canton had been going on for centuries.

And, to cut a long story very short, as Europe became wealthy enough to pay for exotic goods — spices, ceramics and fabrics from the East — that trade was already changing. When the impetus of insistent demand joined up with the profound technological improvements from the West — in navigation, ship-building and, eventually telegraph and much more — the scale of all this trade would change dramatically.

But who would run those ships? Precisely those people whose communities had been doing so for centuries — the Malays, and other peoples from the nations we now call Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Burma/Myanmar and India.

Few of those states, as such, were defined by these names in the early 1800s. Yet Muslim traders long predated the Christians in eastern waters, while Hindus, Buddhists and animists all had long-standing communities which to varying extents were engaged in world trade.

That’s why we have large, deep-seated communities of Indians of many kinds, and Malays and Indonesians and Filipinos and many more, who have called Hong Kong their home for many generations. Today’s domestic helper industry is a late flowering of a much earlier migration pattern.

Boarding houses where the sailors stayed, back in these early days of Hong Kong, were wild and startling places. Sailors would be stuck between ships, or ill or on leave, and not for them the sedate hospitality of today’s Mariners’ Club in Tsim Sha Tsui.

Those homes where sailors first parked themselves briefly, and from where they moved out to make families and build homes, were raucous, frantic and no doubt filthy. And the ladies who helped the men pass their time and money would, in some instances become the mothers of clans, alive and well to this day.

Many people who might see themselves as simply Chinese should not be surprised if their DNA reading showed up hints of this South and South east Asian intercourse. It’s another sign of how communities of many kinds have helped to make Hong Kong the rich and varied place it is.