By Oiwan Lam

A former Chinese solider boasted to a private chat group last week that, during the Sino-Vietnamese War, he killed a Vietnamese woman and raped her teenage daughter.

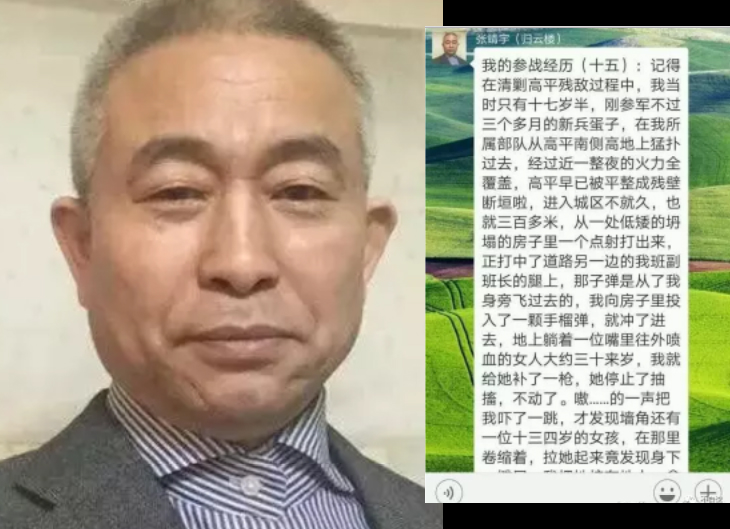

Chinese authorities have been struggling to contain online outrage in response to the post of Zhang Jingyu, a self-described Maoist patriot, who told his story to a private group on the social media platform WeChat.

Zhang described how in 1979, at just 17 years old, he went into the village of Cao Bang in Vietnam in the midst of a crossfire, where he killed a woman and raped her teenage daughter in the ruin.

Zhang was caught by the head of the combat team and sentenced to one week in solitary confinement after he returned to China. After that, the army dismissed him, but recommended him to a college to study foreign languages.

The brief Sino-Vietnamese War was declared by former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping in 1979 after Vietnam invaded Cambodia. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army captured Cao Bang near the border area in less than two weeks, but did not enter the Vietnamese capital of Hanoi.

Deng claimed victory after one month of fighting, and the Chinese forces suffered great losses. In some Chinese oral history records, Vietnamese soldiers criticized the Chinese army of being crueler than US army, which had pulled out of Vietnam a few years earlier after nearly 20 years in the country. Some other English sources also accused the Chinese army of mass killings of Vietnamese civilians when retreating from Vietnam.

In Zhang’s comments, he showed no remorse for his actions:

[mks_tabs nav=”horizontal”]

[mks_tab_item title=”Translation”] Killed her mother, raped her 13-14 year-old daughter. They were all soldiers. During the war, the only good Vietnamese people were the dead ones.[/mks_tab_item]

[mks_tab_item title=”Original Quote”]

殺了她媽,奸了她十三四歲女兒,他們是全民皆兵,戰爭時期的越南人只有死人才是好人。[/mks_tab_item]

[/mks_tabs]

[mks_tabs nav=”horizontal”]

[mks_tab_item title=”Translation”] I did it when I was 17.5 years old. Would you dare to do such a thing? If you did not have the courage, I tell you: you would be lying underneath the hero’s tomb. But I’m still alive…[/mks_tab_item]

[mks_tab_item title=”Original Quote”]

17.5歲我干了,你們敢干嗎?如果說你不敢,那我告訴你:你現在烈士崚園睡著呢,而我還活著。[/mks_tab_item]

[/mks_tabs]

Despite efforts to censor the tale, Zhang’s post has been screen-captured and since has gone viral on Chinese social media. Netizens have widely condemned his actions and called for authorities to investigate the case and clarify the historical facts.

Thus far, there has been no public information regarding an official investigation. But there has been ample censorship of online criticism and discussion about the incident.

Nearly all discussions of the post and associated events have either been censored or are too graphic for public re-distribution. Below is a typical censored comment:

[mks_tabs nav=”horizontal”]

[mks_tab_item title=”Translation”] Even if Zhang Jingyu’s story is a fiction and he never raped the teenage girl or he hadn’t been a soldier at all, his narrative has an adverse effect on the People’s Liberation Army. If he is not punished, there will be more Zhang Jingyus or patriotic thugs who stand out to challenge the baseline of humanity. By then, nothing can be done [to undo the wrong]. Censorship or internet shutdowns won’t work.[/mks_tab_item]

[mks_tab_item title=”Original Quote”]

不管张靖宇有没有强奸幼女,甚至不管他有没有当过兵,他的言论或行为都已对解放军造成极其恶劣的影响,如果他不受惩罚,将会有更多的张靖宇王靖宇以爱国贼的身份站出来,挑战人类的底线,到时候你莫说删贴,就是断网都没用。[/mks_tab_item]

[/mks_tabs]

Those who managed to climb over the Great Firewall left their comments on Twitter. Below is one:

·#杀死孩子母亲、强奸13岁少女,这在哪个国家都是重罪。可是,在共产党的中国、一名中国人民解放军战士,在犯下如此重罪时,却只受到脱去军装、禁闭一周的处罚。至今,他不仅不忏悔,反而在微博洋洋得意炫耀。请大家记住他的丑陋面貌,并请记住他的名字,他叫:张靖宇,网名:归云楼。

· pic.twitter.com/DscHFdADB5— 付振川 (@FuZhenChuan) September 21, 2017

“Killing kid’s mother, raping a 13-year-old teenage, these are serious crimes in any country. But in CCP’s China, when a People’s Liberation Army soldier committed such serious crimes, the punishment was dismissed from the army and one week solitary confinement. Till now, he did not have any remorse and boasted about his crime. Please remember this ugly creature and remember his name: Zhang Jingyu. Screen name: Gui Yun Luo.”

As all criticisms on Chinese social media platforms were censored, Chinese blogger Li Hanfan decided to praise Zhang for telling the truth about the Sino-Vietnamese War:

[mks_tabs nav=”horizontal”]

[mks_tab_item title=”Translation”] Up till now, we had no evidence to prove if Zhang Jingyu was telling the truth. But in my opinion, it now seems more probably that he was telling the truth. Any logical person would not defame themselves with such a serious crime. If it is not self-defamation, Zhang is reviewing history and retelling historical facts. This should be praised.[/mks_tab_item]

[mks_tab_item title=”Original Quote”]

到目前为止,我们无从证实张靖宇所说的是否属实,依笔者看来,属实的成分应该较大。从逻辑上来讲,没人会无端污蔑自己犯下了如此重罪。如果不是自污,那张靖宇就是在回顾历史、还原史实。这种行为难道不值得点赞吗?[/mks_tab_item]

[/mks_tabs]

The blogger then argued:

[mks_tabs nav=”horizontal”]

[mks_tab_item title=”Translation”] What we, in particular our government and our army, need to do now is to investigate if Zhang Jingyu is telling the truth. If he is, then we have to take the history seriously. Our government and army should apologize sincerely to Vietnam and compensate for such serious crimes. We should even send this devil to military court. Of course, it is also possible that Zhang Jingyu had made up the story, he just wanted to be famous…If this is really the case, our government and army should investigate thoroughly and explained the situation to Vietnam. Then punish the rumor creator who has defamed our admirable soldier.[/mks_tab_item]

[mks_tab_item title=”Original Quote”]

我们现在要做的,特别是我们的政府和军队要做的,就是要查证张靖宇所说的是不是事实。如果经过调查张靖宇所说属实,那么…我们当然也必须正视历史,接下来我们的政府和军队要做的,就是为这种暴行向越南方面做出真诚道歉、实际赔偿,甚至把这个在战时向越南平民施暴的恶魔送上军事法庭。 当然,不排除另外一种可能,那就是张靖宇说的这些不是事实,他自始至终在胡说八道,他想用这种噱头让自己变成网红[…] 如果真是这样,那就更需要我们的政府和军队做出详尽的调查再向外界特别是向越南方面做出最具说服力的解释和说明。然后,再让这个抹黑我们伟大军队、污蔑我们可爱子弟兵的“造谣者”受到应有的惩罚![/mks_tab_item]

[/mks_tabs]

The response to Zhang’s comments underlines the imbalance that many Chinese netizens see in the state’s approach to so-called “rumors” online. While some types of political content are subject to heavy censorship, others are not.

Earlier this month, officials released new regulations that hold people who run chatrooms and message groups — who are often just regular citizens — criminally liable for the circulation of rumors, scams and politically sensitive topics in such online groups. Many say the crackdown has targeted views that are critical of the Chinese government and party authorities. Yet speech that is framed as being patriotic — even when it is as inhumane and bellicose as Zhang’s — is spared punishment.

This post was originally published on Global Voices.