Twenty-six-year-old sailor Fang Lang was lashed to a floating piece of the Titanic when one of its few lifeboats spotted him, half a world away from his hometown Hong Kong.

Fang had tied himself to the wreckage before he lost consciousness, and as the frigid North Atlantic swell washed over him, it wasn’t clear whether he was alive or dead. In any case, an officer on the lifeboat reasoned, “there’s others better worth saving than a Jap.”

Others on board disagreed. They pulled forward, plucked him from the sea and warmed him up. Fang, barely alive, sprung to action when he noticed another passenger rowing himself to exhaustion, taking the oar and “working like a hero,” the same officer noted.

“I’m ashamed of what I said about the little blighter,” he later admitted. “I’d save the likes of him six times over, if I got the chance.”

Fang was one of eight Chinese aboard the RMS Titanic when it struck ice on 14 April 1912. They were all men at the literal and figurative bottom of shipboard life—stokers due to shovel coal in the bowels of another steamer that would take them from New York back home. Yet all but one made it onto a lifeboat, and six of them survived the ordeal.

Besides citizens of the Ottoman Empire, they were the largest group of non-European or North American passengers aboard. Their 75 per cent survival rate was surpassed only by the Japanese—with just one second-class passenger on the ship—and the Spanish, who were concentrated in First and Second Class and included several women.

In a wreck where the call to save “women and children first” was widely obeyed, that’s close to ten times the proportion of men in second class who lived, and also much higher than the proportion of third-class women and children who made it onto lifeboats.

The six men’s appearance on the responding ship Carpathia inevitably raised eyebrows. “No one could tell where the Chinese came from, not how they got in the boats, but there they were,” reported the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on April 19th, 1912. Vanishing from the history books in the disaster’s aftermath, their absence has left even more questions unanswered.

That’s where maritime historian Steven Schwankert comes in. His upcoming documentary The Six picks up where their trail turns cold, aiming to find out what happened next to the survivors. He says their story is “one of courage and of quick thinking,” not cowardice.

“We don’t accept the history as it is presented,” Schwankert says, ”we don’t believe these guys just disappeared.” So far, he and director Arthur Jones have been to the home village of at least one of the men, and have traced their descendants to the US, UK and Canada.

“The Titanic is the alpha and the omega of shipwrecks,” Schwankert says. “To connect China and the Titanic in a meaningful way, I can’t imagine that anyone would turn down that chance.”

During the official investigations into the sinking of the Titanic, the ship’s owner J. Bruce Ismay, who was on the same lifeboat as two of the Chinese survivors, said they only “found four Chinamen stowed away under the thwarts” after the boat was already in the water. Schwankert, however, is keen to dispute this. “No matter what Ismay said or thought, they were not stowaways on any lifeboats,” he says.

The “women and children first” code was known as the Birkenhead Drill, after a Royal Navy troopship that foundered off the coast of South Africa in 1852. As she slipped below the waves, the soldiers on the HMS Birkenhead mustered on deck, holding fast in their ranks while the officers’ families boarded the ship’s boats safely and made way for the shore.

Queen Victoria herself ordered a monument for the heroes of the vessel. Their actions became a hallmark of restraint, honour and a kind of quintessentially British sang-froid in the face of certain death.

“It was a sign of the Edwardian times,” says Dr Aidan McMichael, chairman of the Belfast Titanic Society. “Men were expected to be stoical and put women and children first.”

J. Bruce Ismay was pilloried not only for the liner’s lack of lifeboats but also for boarding one of those boats himself. Even though lifeboats were sent down with empty seats when not enough women and children, McMichael says, men who survived stood accused of stealing their spot from a woman or a child. Ismay was “vilified in the press for saving himself.”

“Ismay is still criticised for it even today,” adds Titanic historian George Behe, by people “who point out that the Titanic’s captain and her builder made no attempt to get into a lifeboat—and both men were lost.”

In the U.S., still in the throes of widespread anti-Chinese sentiment that had led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the six were the latest manifestation of a dangerously different “other”: sneaky, inscrutable and unconstrained by gentlemanly manners. According to Behe, false rumours even circulated that the men “disguised themselves as women by loosening their pigtails and letting their long hair fall around their shoulders.”

They alone, among the survivors, were singled out for exclusion and turned away at Ellis Island.

Whether or not they set out for obscurity, they could hardly be blamed for desiring it. Today, little is known about the six—not even where their ancestral villages lay or whether they ever returned there.

They may have been lost to time but the Titanic itself, in a way they would have struggled to foresee, has become a pop culture touchstone in their native land thanks to the runaway success of James Cameron’s eponymous 1997 film.

Titanic dominated the box office was it was released in China one year thereafter, setting records that would endure for years. Fifteen weeks after its release, the film was still number one across the country. It wasn’t the first Western film to hit the big screen, but it was the first to become a nationwide phenomena in a country still catching up after decades of isolation.

Theories behind the movie’s fame abound. State-run newspaper People’s Daily suggested it stemmed from Chinese people’s taste for a good, old-fashioned romance. At a time when China was rapidly moving away from collectivist ethics and people raced to get rich quick, they took solace a tale where love trumped all, including materialism and class divisions.

Ethnographer James Watson, Fairbank Professor of Chinese Society and Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus at Harvard University, posited a more sinister interpretation. He wrote that Chinese cinema-goers identified with the doomed young lovers Jack and Rose because they, too, had been robbed of their innocence and their best years by an historical tragedy: the “ten lost years” of Mao’s disastrous Cultural Revolution.

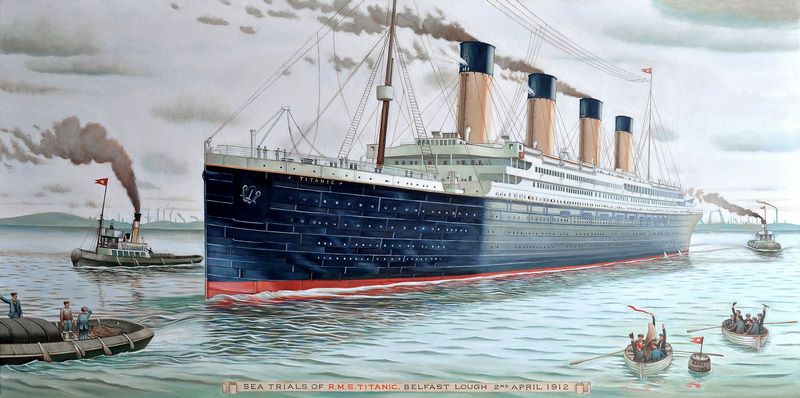

The last known photo of the #Titanic afloat. Photo taken on April 12, 1912. pic.twitter.com/bsU0erbcjj

— History Photographed (@OldHistoryPics_) April 14, 2018

When a roaming exhibition on the Titanic that arrived at the Guangdong Provincial Museum last month, throngs of these fans were willing to pay the steep RMB 80 (HK$94) entrance fee to view its hundreds of salvaged artefacts in the otherwise free museum.

“With more than 25 million visitors to date, we consistently see how Titanic resonates and touches everyone,” says Bao Daoping, who heads the company behind the showcase. “Each of us can relate to someone on Titanic.”

But amongst the dozens of victims’ and survivors’ tales, visitors will not find those they might have related to best. Their countrymen’s names are mentioned just once, lost among those of the ship’s other 3,327 passengers and crew on a vertiginous memorial wall—the last thing visitors see before they walk out.

Even in their home country—and province—the story of the six remains obscure and riddled with inaccuracies, conflicting accounts and enduring mysteries. But according to Schwankert, that could be about to change.

“This isn’t just a Western story,” he says, “it’s a global story. And now, a Chinese story.”