China executed more people in 2016 than all other countries in the world put together, human rights NGO Amnesty International said a global review of the death penalty released in Hong Kong on Monday.

The precise number of executions is considered a state secret, shrouded by a complex set of laws. Amnesty itself stopped publishing exact figures – which it believed to be low estimates – after it became concerned that the data was being used by the Chinese authorities to demonstrate that its efforts to reduce executions were successful.

Whilst China has been taking steps towards reforming its death penalty policies, it is hard to assess the progress without more transparency, William Nee, the lead author of the report told HKFP.

Nee said that one positive trend is that the Chinese government says it did not hand down any death sentences with immediate execution to corrupt officials last year, except for one who committed murder.

Database incomplete

Amnesty researchers uncovered hundreds of cases missing from the new Supreme People’s Court online database that the government had hailed as a “crucial step towards openness” for its judicial system. It found news reports of at least 931 people executed between 2014 and 2016, but only 85 of these cases were included in the database, it said.

“It’s a positive first step, but it doesn’t go nearly far enough,” Nee said. “the database as it is right now is not complete. And that’s one of goals, its self-described goals, to operate on the principle of openness, to be complete. And it’s not at this point.”

The database, which states the values of openness and transparency on its website banner, was launched in 2013. It does not publish details of cases involving state secrets, divorces, and crimes by minors.

False convictions

Over the past few years, the risk of innocent people being executed for crimes they did not commit has caused increasing alarm among the public, the NGO said.

In December, a Chinese court overturned the original verdict for a 20-year-old man, Nie Shubin, who was executed in 1995 for raping and killing a woman, after his family’s decades-long fight to exonerate him. In another case, the wrongful execution of an Inner Mongolian teenager in 1996 – 18-year-old Huugjilt – led to 27 officials being punished in February 2016.

Death sentences for four people were retracted in 2016 after the courts decided they were innocent, Amnesty said.

“These cases of wrongful execution and wrongful sentencing have had a big impact on the public in general,” Nee said. Cases such as these were part of the reason why the government switched its policy to “killing fewer, killing cautiously” in the mid-2000s, he said.

Information on foreign nationals given death sentences for drug-related crimes is also missing from the database, which could prove problematic for China’s relationships with other countries who want to work with the country to curb the drug trade, Nee said.

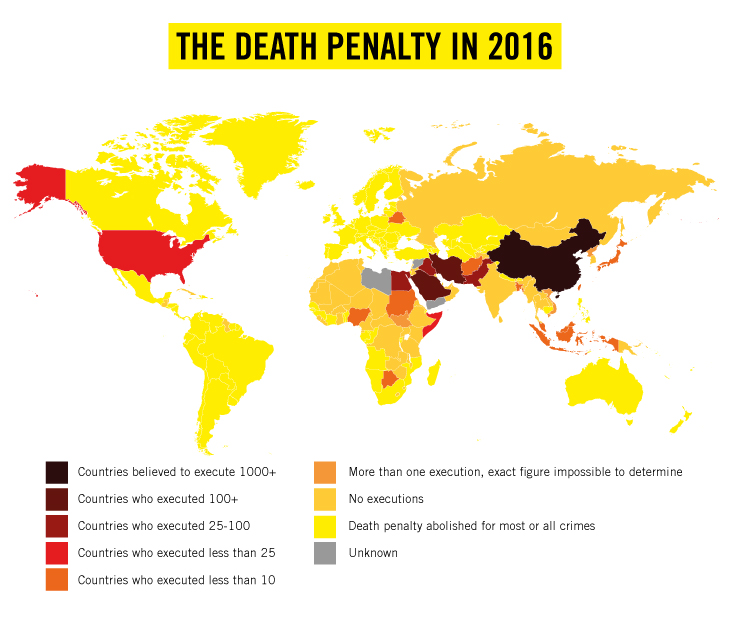

Globally, Amnesty counted 1,032 executions worldwide in 2016 – excluding China – down from a spike in executions in 2015. The US, meanwhile, saw the lowest number of executions since 1991.