By Brianna To and Eunice Ip

On February 28 last year, Au Nok-hin posted a picture of himself on Facebook wearing a tuxedo, standing beside his bride. In the picture, the couple are pointing to a big yellow banner next to them that says: “This Way to Polling Station.”

The humorous gesture is typical of the 30 year-old political geek and district councillor for the Lei Tung I constituency. Even on the day of his wedding banquet, he did not want to pass up an opportunity to urge people to vote in the Legislative Council by-election for New Territories East.

Au has been immersed in politics since his undergraduate days as a government and public administration major at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). During his student years, he was active on the campus radio station and served as an officer in the Student Union. These roles gave him his first taste of political activism.

“I experienced different kinds of political incidents at that time,” he says. The ones he remembers most clearly are the controversy over an article about sexual taboos like bestiality and incest in the Student Union magazine, Chinese University Student Press, which was slammed as immoral and obscene by groups outside of the university, and the tensions between students and then vice-chancellor, Lawrence Lau Juen-yee. Au was a member of a student group set up to monitor Lau’s university policies.

“I think I was an angry youth (fenqing 憤青) when I was still studying in university,” says Au. Asked to define an “angry youth,” Au ponders a while before saying it should involve a sense of romantic idealism, the idea of a university student who cares about society and enters society to try to change it.

Over the years working in the nitty gritty of politics, Au thinks he has learnt to temper his idealism in order to realise his ideals, while holding onto his pledge to “never forget the original intention.”

After following up his first politics degree with a Master of Philosophy degree in politics, also at CUHK, Au entered politics with one goal – to join a district council to give a voice to the public. He joined the Democratic Party in 2009 because it was the pro-democracy party with the most developed district work and community networks.

At the time, Au’s district council goal seemed foolhardy. He recalls the pan-democrats had taken a terrible beating in the 2007 district council elections, reversing the enormous gains they had made on the back of the massive July 1 protest in 2003. Au says an influential newspaper article at the time revealed the extent of the pro-establishment camp’s grip on local politics, the effectiveness of its district organisation and its vast resources. This only strengthened his resolve to break the camp’s grip on local government.

“If the situation continues, all seats in the council will belong to the pro-establishment camp. I thought I should come out and stand for the election. I wanted to prove that the circumstances can actually be changed,” says Au.

Two other factors influenced Au’s decision – one was his time as an exchange student in Japan. During his year in Tokyo, Au was struck by its community administration and how much autonomy its communities had. “They even designed their own drain covers and street lamps; they have their own community halls,” he says admiringly. The other was his university thesis on district council funding mechanisms, which he concluded were unfairly skewed towards pro-establishment organisations.

After volunteering as a community officer for the Democratic Party’s Kam Nai-wai, Au stood and won in the mainly working class district of Lei Tung I in 2011, at the age of just 24.

Au is considered to be a relatively radical democrat and many have wondered why he joined the relatively moderate or some would even say conservative Democratic Party. He admits he has struggled over this himself. He says he does disagree with the party over issues such as how to best achieve the democratic aims of true universal suffrage and the building of the third runway at Chek Lap Kok airport. But he keeps going back to the party’s role in district work. “Back then it was hard to imagine that one person could organise a list and run in an election,” he says.

Au has served in the party’s central committee and twice run unsuccessfully for the party leadership. He says he saw his role as something of a “young turk” trying to modernise and change the party but he thinks that role should now be taken up by the young democrats who have been elected to the Legislative Council.

“I felt like I’m urging the party to change its position and stance and I’ve experienced a tug of war,” Au says. “The struggle ended when I finally figured out my role last year.”

That role is as a connector between the Democratic Party and other pro-democracy forces and civil society organisations. He wants to help build a platform to help progressive forces to work together on common causes. It was in this spirit that he accepted the job as the convener of the Civil Human Rights Front.

“I think the Civil Human Rights Front can serve as a platform to gather and consolidate mainstream discourse among democrats to respond to the challenges brought by the regime,” he says.

Another area where Au has sought to work with other political parties and groups is on opposition to Link Real Estate Investment Trust (Link REIT). Ironically, his activism on this issue has invited criticism from those who berate him for being a member of the Democratic Party, which they point out voted in favour of establishing Link REIT in 2005. Au finds this exasperating. “Dude, that was a long time ago, before I even joined the party!” he exclaims.

Au’s opposition to Link REIT for driving up retail rents and driving out small businesses from housing estate malls became one of the reasons he decided to stand for election in the Legislative Council’s wholesale and retail functional constituency last year. Au says that as part of the move to challenge the establishment on multiple fronts after the Umbrella Movement, he and some like-minded democrats looked at the functional constituencies. He noted that the wholesale and retail seat had been unchallenged for a long time and had a relatively large voter base. It was also a sector to which he had a connection due to his family’s clothing retail business. He took six months to join his family’s company and become first an elector, then a candidate in the constituency. It was the first time a pan-democrat had stood. Although Au’s loss was unsurprising, he did well to win more than a third of the votes cast.

Au says he did struggle a little over using his family’s company as the springboard for his bid but in the end his campaign did not hurt relations with his family. On the contrary, he says, he feels he has a deeper understanding of the sector and of the plight of small businesses in Hong Kong, especially in light of the high rents.

Au sees an ideal community as one where everyone can settle down and get on with their pursuits. “In an ideal community, you’d be able to have a space when you want to open a small store. You deserve this kind of space, why can’t Hong Kong provide it?”

The community is where the former “angry young man” feels rooted. After seven years in Lei Tung, five as district councillor for Lei Tung I, he feels attached to the local community and the residents. He treasures being able to interact with them directly and listen to what their concerns are.

Au says his office is like a community centre where residents just drop in to chat. He says he was a little unnerved when DAB rivals opened an office in the neighbourhood and handed out bags of rice to the residents. “I thought ‘ah, we can’t compete with them in terms of benefits, not by a long shot’,” Au recalls. But then a funny thing happened, he continues. The residents took the rice and then all came in to chat in his office. They were commenting on how small the bags of rice were and about the offering of freebies for political favours.

“If your bonding with the neighbourhood association is strong, the challenge of bribes doesn’t really matter,” says Au.

And he does have bonds in the community. Au is moved when he talks about witnessing the changes in the community in the past five years. “I saw many residents forming their families and I saw many of the supportive residents pass away,” he says.

Au says he is invited to many funerals and that he has helped a lot of residents to write their wills. He is bemused by how this has become one of his unofficial jobs as a district councillor. He reckons he has helped residents make around 250 wills, possibly more than the lawyer who taught him how to do it.

“Maybe it’s by word of mouth. People keep asking me for help in making a will. Four copies are waiting for me this week,” says Au. But he’s not complaining – he thinks this kind of service is putting his motto of “making district work the priority” into practice.

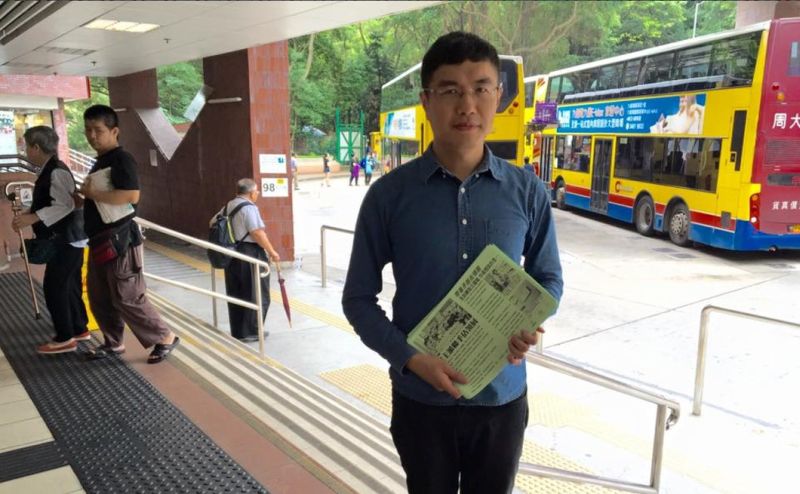

“It’s all about treating people with sincerity. This is how I get along with the residents.” Describing how he maintains his district work, he says the first thing is to have personal interactions by standing in the street. The second is to provide online channels for those who prefer to find him this way.

After seven years in politics, Au is thankful to community work and to the residents he serves for keeping him grounded. He sees being detached, or literally in Cantonese “off the ground,” as a danger that affects both those in the establishment and the democratic camp.

“An important thing community [work] has taught me is the meaning of ‘detached’, it’s when you don’t think what the residents are thinking,” says Au. “For people to ‘buy’ what you say, it has to resonate with how they really see society. And what you need to give people is a direction to articulate how to make a change. That’s what a politician needs to be able to do.”