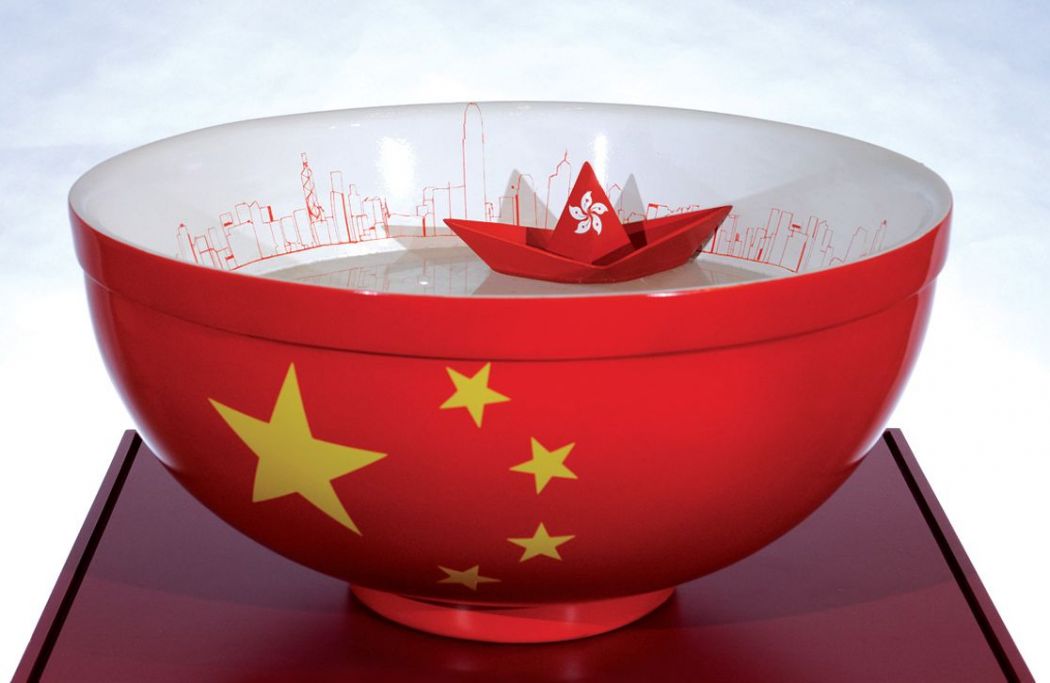

Can 51 hours of Basic Law education smother the separatist sentiment of our disaffected youth in Hong Kong? This question, in essence, drives the proposed update of the Secondary Education Curriculum Guide, announced by the Education Bureau on Monday and mentioned in Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying’s final Policy Address.

This Basic Law instruction is a complex equation of 24 lesson hours in Chinese History (a subject highlighted in the Address as well), 15 hours in Life and Society, 10 hours in History, and 2 hours in Geography within the three-year Junior Secondary (Grades 7-9) academic structure.

It will be promoted through ‘continuously developing learning and teaching materials, organising relevant learning activities, providing teacher training and conducting exchange programmes with Mainland students and teachers so that students can “properly understand” the important concept of “one country, two systems” and the fact that Hong Kong is “an inalienable part of the People’s Republic of China”.

It’s all well and good, isn’t it?

Hang on a moment. The Basic Law and national identity are included in the General Studies curriculum in primary education. The current Moral and Civic Education framework has ample room for achieving the same goal. Isn’t this amount of additional instruction excessive while equally important subjects like physical education, music, sex education and visual arts are edged further out as a result of timetable squeeze?

Clearly, the call for strengthening Basic Law and Chinese history education is not only a knee-jerk reaction to the rise of separatism, but also resurrects the derailed national education curriculum that pretty much toes the line of Beijing.

Why? In the eyes of some politicians, school curriculum is still a lethal weapon of mass instruction. In Liberal Studies, students are inevitably exposed to sensitive political topics such as the Occupy movement and the lawmakers’ oath-taking controversy in October, which perfectly fit the subject’s constituent themes of the rule of law, socio-political participation and identities. Alarmed by this Pandora’s box, the conservative force is now striking back: let’s read more about the Basic Law and Chinese history.

But will the power of anti-Chinese sentiment atrophy because of this 51-hour instruction and an extra dose of Chinese history? It won’t, because no conclusive evidence suggests that curriculum and teachers have anything to do with political change.

The odds, however, are that endless political debates will surface again. Just imagine: in a Basic Law education lesson, if students recontextualise the concepts of “two systems”, “sovereignty”, “a high degree of autonomy”, and “Hong Kong people administering Hong Kong” as “Hong Kong is an independent sovereign city-state” in their homework, will the teacher be accused of fomenting biased political views in the classroom and hence be subject to disciplinary action?

Mind you: thus far, nobody in Hong Kong can act as thought police to punish anybody for their ‘thought crime’ – for example, Hong Kong independence.

What about field trips and cultural exchange programmes in China? Will these trips indoctrinate our students and teachers in biased political ideology? Well, that these learning activities will amount to brainwashing is exaggerated.

There have always been study tours to the Mainland for Hong Kong students and teachers. I believe these trips did broaden students’ horizons, and to a certain extent, it is a laudable initiative. However, these learning activities may not yield the effects policymakers expected as if students will by default identify themselves more with the Mainland Chinese.

A few years ago while still working as a schoolteacher, I was asked to chaperone a convoy of students on a tour to Foshan, a booming city near Guangzhou. The first impact of modern Chinese civilisation these Hong Kong-born students experienced after crossing the border was the filthy toilets, which they refused to use.

The hotel should be fine, right? Not really. The floor below us was a nightclub for adults. We teachers had no choice but to patrol all night long to make sure all students were corralled in their rooms. It was the travel agency’s fault to book that sleazy hotel for us but looking back, I believe this trip was quite an authentic lesson of national education – compared with Hong Kong, China isn’t that great.

In the end, I dared not read the feedback forms submitted by our students on how they felt about the trip, just in case some inappropriate comments like “I don’t’ want to be Chinese” may appear. Love thy neighbour? Well, better clean up the toilet first, to the Japanese standard.

Nothing worrying, right? Not really. In fact, there are other new moves made by the authority which should be noted with grim dismay. A number of demoralising gestures have already presaged a tightening grip of the state on schools and undermined teachers’ authority.

Last week, the Council on Professional Conduct in Education launched a consultation on reviewing the professional code for teachers. The new code blatantly infringes upon individual civil liberties. One proposed clause provides that a member of the profession “shall pay attention to their own demeanour and conduct, strive to set an example for students to model on, and avoid engaging and participating in work or activities which may threaten professional image.”

At first sight, it sounds acceptable, but the interpretation given by the consultation document is shocking. It reads “teachers should avoid publishing on their own social media sites or instant messaging application such as Facebook, Weibo and WhatsApp any image, text, audio and video that may threaten professional image. They should also avoid discussing with students any issue that is irrelevant to the purpose of teaching and learning.” Isn’t this a violation of fundamental human rights?

These days, we like faulting our teachers and school curriculum for failing to nurture students with “right attitudes”. For example, you have to love your motherland. Like many teachers, I am astonished by this patronising attitude, and the assumption that the onus is on teachers to act as moral crusaders against all sorts of social problems.

I have no idea why this permanent revolution in education is so implacably hostile to our educational professionals and always assumes that our system is in a poor state waiting to be rectified. While practices of the good old days (if any) may not suit the present moment, I believe we should look to the past and existing conditions for inspiration, before adding unnecessary initiatives and throwing the old stuff wholesale into the dustbin.

Let us take a look at the syllabus of Liberal Studies (AS Level) in 1991 and see whether we need this Basic Law education to improve our legal knowledge. Similar to the latest curriculum, the old syllabus also has a module on Hong Kong. It has a section introducing the legal system and enforcement of the law, but is much more concept-rich and firmly grounded in sound legal theory. The following explanation details the concepts of ‘the rule of law’, ‘equality before the law’, and ‘the independence of the judiciary’:

- the principle that no one in a position of power should be able to exercise that power in an arbitrary fashion, and that no one should be allowed to assume a position where they are subject to no one and subject to no control,

- the supremacy of the law in that citizens are ruled by law and by the law alone, that they can be punished for breaches of the law but for nothing else,

- equality before the law in that all, regardless of position, rank or wealth (including the judges and the Governor in Hong Kong’s case) are subject to it,

- the function of the law to uphold and protect fundamental human rights and liberties,

- the right of wronged citizens to have a remedy against the state,

- the presumption of innocence, the right of appeal, and the absence of cruel or unusual punishments in the criminal system of justice,

- the independence of the judiciary in that the appointment and dismissal of judges is subject to rigorous rules and in that they are not answerable to those holding political office (the Governor in Hong Kong’s case) and cannot be appointed or removed from office solely on the wishes of those holding political office,

- the problems that flow from granting public officers discretionary power in carrying out their public duties by authorising them to act: “as they think fit/if they are satisfied… /if it appears…/ if they suspect…”, and the need for adequate channels for redress to protect individuals from the exercise of such discretionary powers,

- the role of the press/media in protecting those who are unable to secure their rights under the law, and in bringing pressure to bear upon public officials to act in accordance with the law.

Doesn’t the explanation above resonate with Lord Bingham’s authoritative work on the rule of law and succinctly encapsulate the common law tradition in Hong Kong? The present LS curriculum still mentions these concepts, but it reduces them down to only three lines:

- the significance and the implementation of the rule of law in different dimensions, e.g. equality before the law, judicial independence, fair and open trial and the right to appeal, legal protection of individual rights, legal restrictions on governmental power.

That’s it. If we want our students to properly understand the “one country, two systems” constitutional principle enshrined in the Basic Law, shouldn’t we join up the dots and provide more concrete knowledge just as our first syllabus did?

The problem of our education doesn’t come from teachers. It is the hollowing-out of knowledge that lies at the heart of our education. I was once in a conference for Liberal Studies teachers where some delegates did try to probe deeper into the technical knowledge about the Sino-British Joint Declaration.

However, adopting an issue-enquiry approach to teaching and learning, the present curriculum and assessment practices “avoid questions which call for detailed factual recall” while emphasis is put on thinking skills. The bullet points above are just too cognitively demanding. Therefore, in the conference, the teachers didn’t pursue further. Conversations about the content knowledge were shut down.

Then what do teachers look for when preparing teaching and learning resources? We will have the rule of law according to Benny Tai or some patriotic organisations. No one is going to judge which set of materials is up to standard and which one doesn’t pass muster.

Then, according to the new professional code, if you use the materials written by Benny Tai, teachers are probably subject to disciplinary hearing and condemned as guilty of spreading propaganda.

The constant change of education policy is a counsel of despair. One goal that the government had once set out in education reform is that our students should be able to “understand their national identity and be committed to contributing to the nation and society”. The reality, however, is the unprecedented surge of anti-Chinese emotions.

Can boxing teachers in by superfluous rules and regulations help our students thrive in the 21st century? Or should we look at what knowledge our students actually learn in schools?