By Andrew S Guthrie

Whenever I engage online with a “pro-China troll”, a 50 cent army employee, or simply (to give them the benefit of the doubt) a concerned Chinese citizen, regarding Xi Jinping’s heavy handed policies or the CCP’s political/economic monopoly, invariably we US citizens are called out and told to “clean up your own backyard” before we criticize the Mainland.

Good advice. The two prongs of my response to this accusation consist of stating that at this juncture we are debating China (so let’s stick to the subject) and that, as a US citizen, I am completely on board with any critique of my country’s shortcomings and have been, throughout my life, calling out the USA’s policies (in particular, its foreign policies).

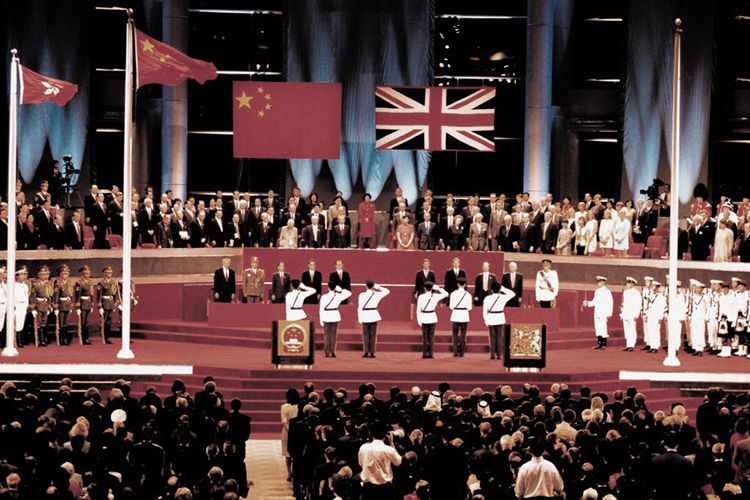

This is to preface a devastating critique of the USA’s interventions in one of its colonies, Puerto Rico (situated directly to the east of Haiti and The Dominican Republic in the Caribbean Sea), and to make it clear now that my purpose (besides acknowledging the USA’s scandalous history) is also to provide a historical comparison with the political struggles of contemporary Hong Kong, and specifically with the pro-independence or separatist inclinations within the pro-democracy camp.

Puerto Rico became a United States’ colony after the Spanish-American War in 1898 (along with The Philippines and many other formerly Spanish territories). This was the war initiated by means of the dubious provocation of the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana’s harbor, but for many years factions within the USA had been itching for a war with Spain and supporting independence movements within Spain’s Caribbean colonies.

The irony should not be lost here even if you are only slightly aware of the outcome of Cuba’s initial independence from Spain (a circumstance that eventually led to the rise of Fidel Castro and Co.). But in a further irony, Puerto Rico, at that moment, had already been granted independence from Spain, an independence that lasted a mere eight days, an autonomy that was interrupted by the invasion and eventual victory of the United States’ armed forces.

This is where the story really gets ugly: a devastating typhoon was greeted by the US banks with a 40% currency devaluation and the jacking up of interest rates, leading to widespread foreclosures on Puerto Rican owned farms. The state of affairs was so lopsided that by 1930 half of Puerto Rico’s arable land was owned and operated by US sugar-producing corporations. Wages also crashed and Puerto Ricans eventually earned half of what they had done under Spanish rule.

The story goes on and on like this, with US moneyed interests and their political allies having the advantage that no one within the USA was really paying attention, and all news from Puerto Rico to the mainland was processed, spun and/or suppressed (the “mainland” in this case being North America). In the meantime, on the island itself there was a successful labor strike, pro-independence movements began to emerge, the charismatic political martyr-to-be Pedro Albizu Campos (first president of the Puerto Rico Nationalist Party) gained the FBI’s attention, peaceful protesters were killed by the police and army, and the pro-independence movement eventually decided to take up arms.

Here is where we reach our intersection with Hong Kong’s own political circumstances. We can see that, thus far, Hong Kong has not met with the utter neglect and violence inherent in the USA’s governance of Puerto Rico. The situation here, as far as the Mainland’s interference in “One Country, Two Systems” is concerned, has been far more underhanded (one might even say: insidious). Hong Kong’s pro-democratic advantage in this case would appear to be two-fold: Hong Kong is a relatively affluent/university-educated society and it not only has a tacitly free press, but it has international news agencies that are paying close attention to political developments on the ground.

There has recently been much consternation about the suppression of “localist” candidates in the Hong Kong elections and inferences that teachers in secondary schools who discuss, or initiate discussions, concerning Hong Kong independence will be sanctioned, if not terminated. The history of Puerto Rico and its colonial overlord is, once again, far more dire. In 1948 a law was enacted that prohibited speaking, writing, holding meetings or protests in support of Puerto Rican independence. Anyone found guilty of breaking said law could face up to 10 years in prison, a US$10,000 fine or both. Even displaying a Puerto Rican flag inside one’s house was a potential breach of the gag order. Despite Puerto Ricans being granted US citizenship in 1917, they found themselves subject to a law that was in direct violation of the US Constitution, a paradox somewhat akin to China’s breaches of the “One Country, Two Systems” legal guidelines. Even so, the law against Puerto Rican free speech, though harsh, proved to be politically ineffective and was eventually repealed in 1957.

Another infamous incident in the Puerto Rico/USA timeline (which also demonstrates that terrorism as a tool for political ends is far from a recent development) occurred in 1954 when four Puerto Rican Nationalists entered and shot up a session of the US Congress. There were no fatalities. I mention this particular incident apropos of the US media’s ability to, rightly or wrongly, frame or suppress any particular story. I was born well after this incident and was only mildly cognizant of international politics by the time my stalwart liberal/progressive parents informed me that the Puerto Rican Nationalists were fanatical or perhaps even “nuts” without giving any kind of context to the historical underpinnings of that movement.

The take-away lesson for Hong Kong in this brief history of colonial rule might be that choosing between China and the USA, or China and Britain, is like the proverbial choice offered between a rock and a hard place, two sides of the same colonial coin as it were. Any armed insurrection (or the option of violence by pro-independence groups) in Puerto Rico was managed and spun on the mainland USA in a way that completely denigrated the cause of independence. Without further parsing the ins and outs of violence as a political tool, Hong Kong progressives can otherwise take serious stock of the continuing advantage of a free press and, thus far, its unimpeded projection onto the international stage.

This article is seriously indebted to WarAgainstAllPuertoricans.com.