The gig economy is one of those phrases that has entered everyday language and become a form of shorthand, losing its pejorative force in the process. How is staying alive and supporting one’s family just a gig?

With the now-settled strike of about 300 Foodpanda workers against tough working conditions and cuts in delivery fees, the heartlessness of the “gig economy” is evident in Hong Kong too. What the workers who deliver our meals must deal with day after day is definitely an alienating job. Their services are counted by the unit. There is no job security but they are the butt of all kinds of criticism. The Foodpanda workers knew this better than most: they are not only paid by the “gig” but are the focus of complaints.

The delivery motorbikes are occupying parking space on the street? Complain. The food has arrived quickly but some of your pizza topping has slipped onto the carton? Complain and don’t tip. Traffic was slow due to an accident or a road closure and your food is not piping hot? Complain, do not tip, and decide you will also write a negative review.

While it is reasonable to expect good service, this must not stop people from empathising with the weakest link in the chain: the worker forced to walk fast up and down Hong Kong’s hilly terrain, the rider who must navigate nightmarish traffic but whose earnings are based on the number of trips.

Not surprisingly, the recruitment page for delivery personnel on Foodpanda is all pink and positive: you can explore the city, have flexible hours, be your own boss, earn a lot and all the tips are yours! You just need a little investment: you must have your own smartphone (that’s right, no company phone) and if you plan to join as a rider, you need your own vehicle with all the necessary requirements. Again, the company will not provide the most essential tools for the job.

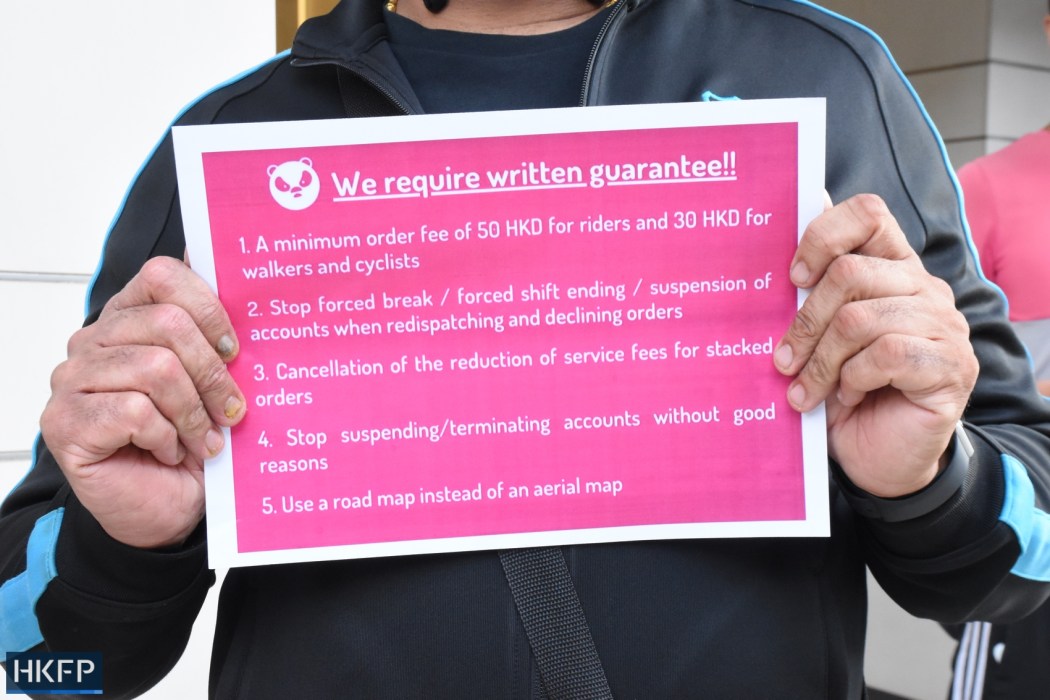

The recruitment page also promises that you can earn more if you refer others – something that sounds a little like a pyramid scheme but maybe it is just the optics. What is not just optics, is how unreasonable the cut in pay proposed by Foodpanda was: riders used to make HK$50 per trip, while those who deliver meals on foot would make HK$35. Those were slashed, to HK$45 and HK$28 respectively, and were meant to go even lower, to HK$40 and HK$22 respectively.

The number of trips which must be made every day to earn a living wage is not so easily calculated, as there are many ways in which “gig” workers can be penalised: if they refuse an order, even for a valid reason, or if the photo they take as proof of delivery is considered too blurry (imagine being in a rush to make ends meet, and having to concentrate on picture perfection so your delivery is not questioned).

The company regional headquarters are in Singapore, and the parent company that owns Foodpanda is in Berlin, called, with no apparent irony, Delivery Hero. The company’s failure to respond to workers’ enquiries and complaints was one of the many grievances raised by the agitating workers.

Throughout the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic the hardships faced by delivery drivers have been highlighted all over the world: just in East Asia, in November last year South Korean delivery drivers were reported to have died of kwarosa, or overwork, after endless unregulated shifts that saw people work for 22 hours non-stop. The South Korean labour ministry stepped in, making major delivery companies sign a declaration that ensured better conditions.

In spite of this, Korean delivery workers were on strike again this year, as conditions had not improved sufficiently, and overwork and lack of guarantees still plague the industry there. In mainland China there are about seven million riders, and they, too, have been trying countless times to organise in hope of securing better working conditions. But they have been let down time and again by the official unions.

In Hong Kong gig workers are not unionised but used to receive some help from the now disbanded Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions. The brief springtime for unionisation in 2019 and early 2020 has ended with the National Security Law, and all the additional scrutiny of organisations seen as opposed to the government.

The workers had 15 demands for the company, which were not just about money. To establish delivery times, for example, Foodpanda uses an aerial map – we all know gig workers must be able to fly – and uses that to judge speed of delivery rather than a street map which would more realistically measure physical distance. Since the end of the protests in 2019 and the beginning of the pandemic there have been very few demonstrations in Hong Kong, but there have been a significant number of non-political mass gatherings that have not raised official concern. And yet, when police decided to show up at a protest by Foodpanda strikers, it was once again the Covid regulations that were cited to tell the workers they were in breach of the law, and they would be dispersed if they didn’t do so themselves.

A summary of the situation shows how deeply flawed the whole system is, and how wrong. What makes matters even worse in Hong Kong is that many delivery workers are South Asian, or of South Asian descent, and are particularly vulnerable: maybe in terms of visas, if they are not permanent residents, but also because of racial discrimination.

Among the 15 demands, one in particular indicates how bad the situation is – number eight asks Foodpanda to educate customers and vendors to be polite. There are even reports of customers asking for their food to be delivered by non-South Asians – something which should be illegal. Racial discrimination in Hong Kong is not debated often enough, but now that solidarity with delivery workers really seems to be of the essence, educating ourselves in not discriminating, and in not treating service workers poorly, must be the absolute priority.

The public could also put put pressure on Foodpanda (through social media, for example, by tagging the company and saying that we support the workers) and on the government, so that a cut-throat yet widely used service does not penalise the most vulnerable link in its chain.

Correction 22/11: A previously version of this article incorrectly stated Foodpanda had no physical presence in Hong Kong.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.