The award of this year’s Nobel Peace Prize to two journalists, Maria Ressa from the Philippines and Russia’s Dmitry Muratov, for their work to “safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace,” is a recognition of the efforts of all those journalists who face threats, arrest, and even death.

Ressa, who runs the news site Rappler, has faced multiple arrest warrants for her reporting, and is facing numerous legal cases related to coverage of the drug war of President Rodrigo Duterte, who describes the press as “the enemy of the people.”

Muratov is one of the founders of the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta. While leading the newspaper as editor-in-chief for 24 years, its critical and fact-based reporting has included coverage of corruption, police violence, election fraud, and the wars in Chechnya. Six of his reporters have been murdered for their work: Igor Domnikov, Victor Popkov, Yury Shchelochikhin, Anna Politkovskaya, Anastasia Baburova and Natalia Estemirova.

Also, in the last two months an unidentified photographer from Myanmar has won both the prestigious Bayeux War Reporting Prize at the Bayeux Calvados-Normandy Award and the Visa d’Or for News – the top award handed out at Visa Pour L’Image festival. He remains anonymous for his own safety in a country where the military junta has jailed journalists for reporting on the coup and its after-effects.

According to Reporters Without Borders, about 100 journalists have been arrested since the coup on February 1 and at least 53 remain behind bars.

On the day the Peace Prize was announced, Russia labelled eight journalists and news outlets as “foreign agents.” They include freelance correspondents for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and the BBC, while the outlets were MNews, Kavkazsky Uzel and Bellingcat. This requires the news outlets to submit to audits and many other restrictions. They must be labelled as foreign agents when cited in media reports.

If they fail to do so, they can face fines or prison sentences. Russia has added 68 people and outlets to the list of 85 since the start of 2021.

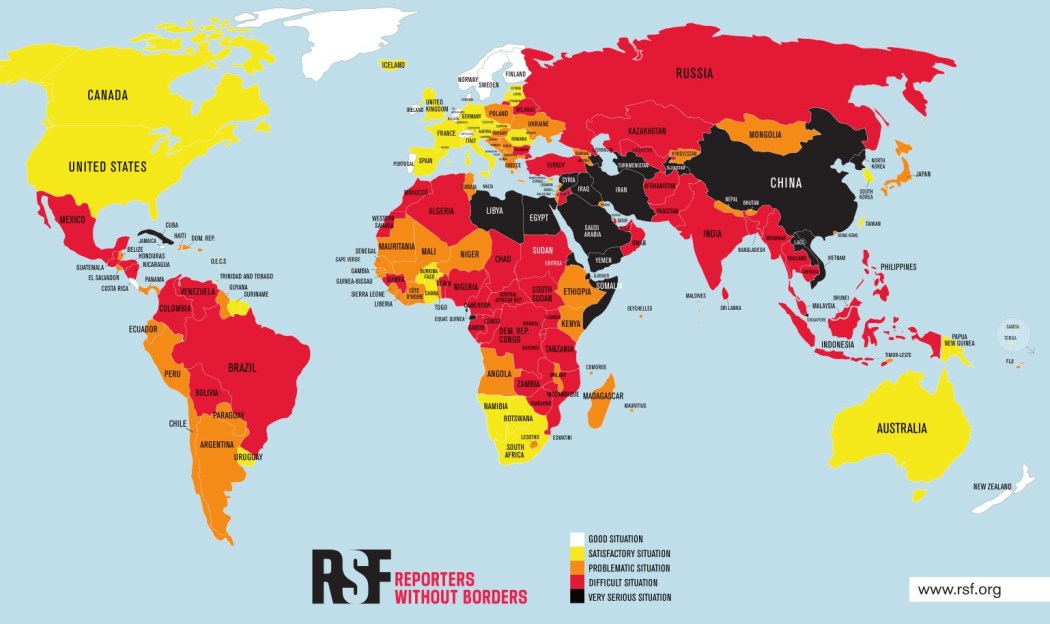

Russia is not the only country to use the law against journalists, citing foreign interference as an excuse.

In early October, Singapore passed the Foreign Interference Act. This new law, under the guise of countering foreign influence, in reality works to block free speech and remove content that the government sees as “fake news” or anti-government. The law would allow the Minister for Home Affairs to require the removal of online content and order the publication of government-drafted stories.

The law allows the minister to designate individuals or entities as “politically significant,” which would prevent them from accepting donations from those who are not Singapore citizens or entities. It could also compel journalists, researchers, and academics among others to reveal their communications with non-citizens.

In Bangladesh, the government is looking to pass a law that would force social media firms like Facebook and Twitter to store their data locally. By doing so, they hope to be able to use the country’s Digital Security Law to force the companies to turn over user data and other information on accounts alleged to spread “fake news” or “propaganda.” The Digital Security Law has already been used to file cases against journalists, and the expanded law would put more people at risk, along with social media users in general.

In the Maldives an Evidence Bill, contains a provision that is an affront to journalists and the free press. Article 136 gives judges the power to force journalists and the media outlets they work for to reveal their sources if ordered by a judge.

The Maldives Media Council and the Editor’s Guild of Maldives have said they fear that sources would be reluctant to report on corruption and other issues. They say the legislation would lead to a decrease in press freedom, which is a right guaranteed by the constitution.

Hong Kong’s National Security Law, which went into effect in June 2020, has had a chilling effect on the media in the city. It has led to the closure of Apple Daily, the arrest of numerous of its chiefs, and attacks on the Hong Kong Journalists Association, among just name a few incidents. Four United Nations rights experts are calling on the Hong Kong Government to launch a review of the law, stating that it is incompatible with international law and human rights standards.

Reporters Without Borders counts 471 journalists currently sitting in jail for their work. With the legislation proposed or in force in Singapore, Bangladesh and the Maldives along with other countries, that number is certain to rise.

On top of that figure, RSF counts 29 journalists who lost their lives this year alone. So far in October Raman Kashyap was killed in India on October 3rd and Shahid Zehri in Pakistan a week later. Their deaths, along with those of the six reporters for Novaya Gazeta, count among the 1,416 journalists killed since the Committee to Protect Journalists began keeping records in 1992.

As countries combat “fake news” and “foreign interference” though draconian laws and the arrest of journalists, or even murder those seen as a threat, no amount of awards or recognitions will keep journalists safe. Every arrest or murder is an attempt by those in power to maintain control at the expense of democratic norms and human rights.

The announcement of the Nobel Peace Prize perhaps sums up the sentiment best:

“Free, independent and fact-based journalism serves to protect against abuse of power, lies and war propaganda. The Norwegian Nobel Committee is convinced that freedom of expression and freedom of information help to ensure an informed public. These rights are crucial prerequisites for democracy and protect against war and conflict. The award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov is intended to underscore the importance of protecting and defending these fundamental rights.

“Without freedom of expression and freedom of the press, it will be difficult to successfully promote fraternity between nations, disarmament and a better world order to succeed in our time.”

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.