Hong Kong, for now, is a tale of two cities. In one part of town, demolition work has moved into high gear as the police and the courts proceed to dismantle the old order with its democracy movement counter-current. The old order can now be defined as the first two decades of post-colonial rule, when the handover agreements between London and Beijing still mattered . The dividing line between old and new is clearly drawn in the form of Beijing’s National Security Law, promulgated for Hong Kong on June 30, 2020.

Out with the old

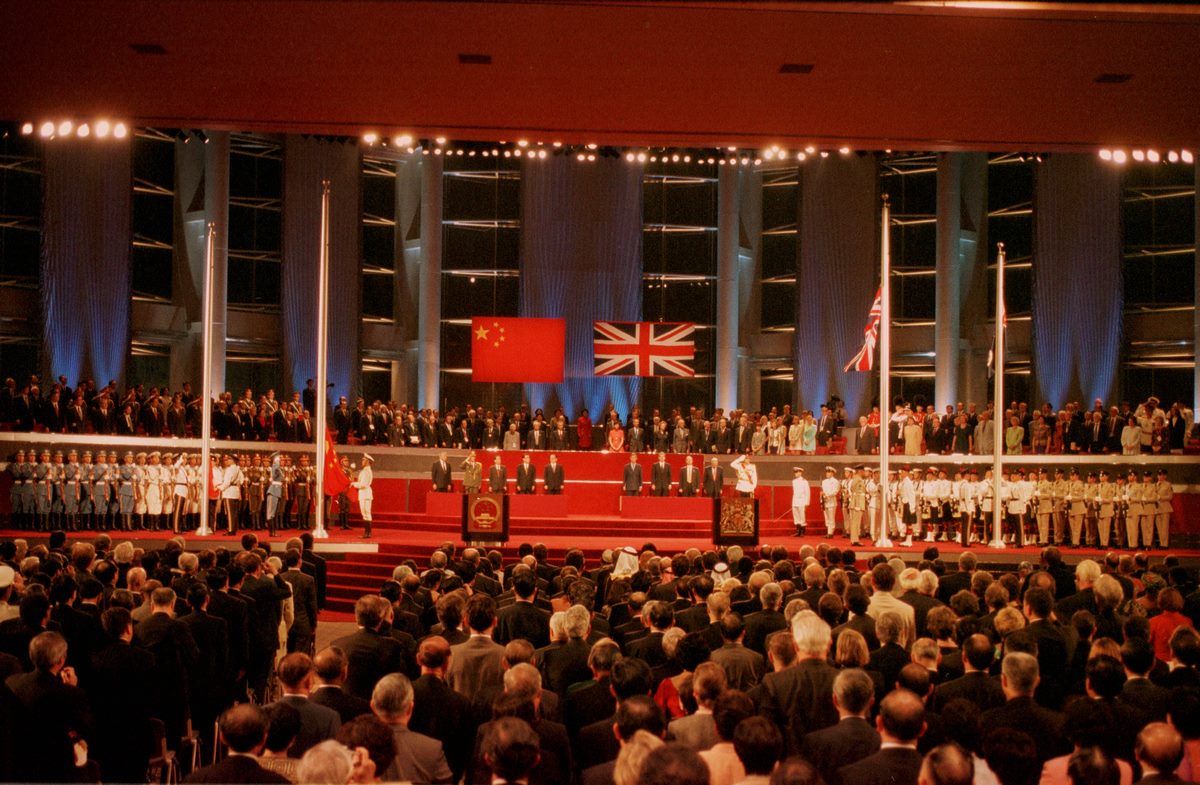

The target is Hong Kong’s democracy movement that began to grow in the mid-1980s as soon as Beijing announced its plans to resume sovereignty over Hong Kong come 1997. By 2019, that movement — to establish the principles of Western-style democracy with all the usual rights and freedoms — had reached a point where it could challenge the political design Beijing had been trying to establish here since 1997.

The design was called “one-country, two-systems” and was written into Hong Kong’s Basic Law constitution. Promulgated in 1990, the law was drafted by Beijing for Hong Kong’s post-1997 use. And therein lay the heart of contradiction.

The Basic Law promised all the familiar Western-style rights and freedoms: speech, publication, education, religion, an independent judiciary. It even promised universal suffrage elections for both the Chief Executive and all members of its local legislature.

Hong Kong’s democracy movement grew up living by these promises and provisions, but they were never clearly spelt out. In fact, only now is everyone finally learning, the hard way, that they evidently meant one thing to Beijing’s Communist Party rulers and another to Hong Kong’s Western-oriented democracy movement.

The clash of political cultures and political interpretations was evident even from the start, while the Basic Law was being drafted in the late 1980s. But as the years passed, Beijing’s excuses and delays failed to induce forgetfulness.

The contradiction between what people thought they had been promised and what was being delivered reached a stalemate in 2014-15, over the issue of universal suffrage elections for Hong Kong’s Chief Executive. At that point, patience ran out on both sides as it became clear: Beijing was only offering a mainland-style version of universal suffrage, meaning one-person-one-vote to endorse Beijing’s designated choice of candidates. And that was all Beijing was ever going to offer. The insurrectionary uprising of 2019 followed accordingly, although initially precipitated by a different issue.

It remains unclear to this day whether Beijing leaders and Deng Xiaoping actually intended to honour all the rights and freedoms they promised in the Basic Law. Or whether present leaders, with Xi Jinping at the helm, could not live with the unanticipated consequences once Hong Kong’s democracy movement finally grew strong enough to demand, as its right, what had been promised in the 1980s. Beijing’s final answer, ending all debate and discussion, was the National Security Law.

Since its promulgation last year, most of the principal players who were committed to the democracy movement’s ongoing campaigns for Western-style reforms have either been arrested or fled to safer shores overseas. Increasing numbers of former political leaders have been tried, found guilty, and are now serving prison sentences for security crimes.

The charges against them and others range from illegal assembly to the most serious under the new law: subversion, secession, terrorism meaning political violence, and collusion with foreigners for political aims here.

The civil society groups and alliances which these leaders founded are being disbanded and subjected to daily blasts of hyper-vilification in the local Beijing-sponsored press. They are now the targets of an old-style political rectification campaign designed to discredit and delegitimise — thereby setting the stage for a new set of leaders waiting in the wings.

In with the new

Elsewhere, in other parts of town, different scenarios are being played out as the groundwork is laid for the new leaders about to make their entrance. They are tasked with creating the new way of political life that Beijing now seems determined to try and establish here. It’s grounded in the basics of Communist Party rule that large numbers of Hongkongers had been trying to keep at bay since the early 1980s, when the news first broke of Beijing’s 1997 plans.

When the National Security Law was promulgated last year, no one knew what to expect or what kind of political system would emerge. The first major step in that direction was the complete redesign of Hong Kong’s post-1997 election system. This was the system that Hong Kong’s pro-democracy politicians and partisans had finally begun to master.

In order to eliminate that danger — of their winning a majority in the coming Legislative Council election as they had already done in the 2019 neighbourhood-level District Councils — the new rules entailed disqualifying and removing most of the incumbents from the most recent 2016 and 2019 local elections.

Meanwhile, a new electoral system had been designed and was promulgated by the central government in March this year. The aim is to ensure that no candidates such as those previously elected can ever again aspire to win seats in any of Hong Kong’s elected councils. It is a drastic reversal of all that has gone before, and a deliberate rejection of what officials refer to as Western political ways.

Lau Siu-kai — professor emeritus, government adviser, and now prominent spokesman for Beijing’s political initiatives here – put it this way: “Under the new electoral system, anti-China and anti-communist opposition forces in Hong Kong will be completely excluded from the upcoming elections. Aspirant politicians from the radical opposition can never pass the stringent political allegiance tests applied by the newly installed vetting mechanism. Accordingly, only patriots will be able to take part in the elections and enter the governing bodies of Hong Kong.”

The new system has many interconnected parts. Key to all, as Lau suggests, is the vetting mechanism that guards the gate. If the new standards are applied throughout the coming election season, and continue to be, then few of the democracy movement’s most electable politicians will ever be able to make a comeback. And if the voting public’s preferences do not change in deference to the new rules, voters will be hard put to find candidates of their choice.

Back to the future?

What kind of government this will produce is anybody’s guess. But the ideal type from Beijing’s perspective must be what mainland officials saw in pre-1997 colonial Hong Kong. In the 1990s, after the last British Governor Christopher Patten embarked on his go-it-alone better-late-than-never electoral reform experiment, the officials were incensed. They refused to have anything to do with any part of his project.

By way of a reprimand, one of their favourite lines at the time was that Hong Kong had always been an “economic city,” and should remain true to its foundations. Beijing decision-makers must now be calculating that they can return Hong Kong to its pre-political state — as an entrepot trading port city — and carry on as the British did before Patten.

But the British called their rule here a “benign autocracy.” Hong Kong is now under Communist Party rule and the new national security regime is not benign. Hongkongers have also learned how to use the new ideas that officials find so unsettling. Once subjects have evolved into citizens, and everyone gets used to having their say, reversing course is difficult to engineer. Beijing is nevertheless doing its best.

The new arrangements – overall

The coming election season will feature three related sequences. First will be the creation of the now all-important Election Committee. But basically, this job has already been done — by design and prior appointments. The finishing touches are to be added with the subsectors election scheduled for Sunday.

This committee has been expanded from 1,200 to 1,500 members. Its main task is to endorse Being’s preferred candidate to serve as Chief Executive — essentially a formality by the time votes are cast, which will be early next year.

But under the new rules promulgated by Beijing earlier this year, the Election Committee has been significantly upgraded. Besides endorsing the Chief Executive, the committee will now simply select, from among its own members, 40 individuals to serve concurrently as members of the new Legislative Council (LegCo).

Finally, the Election Committee is responsible for nominating all aspiring Legislative Council candidates. They cannot contest without the signatures of at least 10 Election Committee members, at least two of whom must be from each of the Election Committee’s five sectors.

This would almost automatically eliminate most pro-democracy contenders, assuming the vetting committee gives them a pass, since membership in the sectors has been meticulously rearranged and coordinated. The aim is to ensure that all five sectors are now stacked with “safe” members.

These members are from groups and associations of groups — some old, some new — that extend throughout the community at both elite and grassroots levels. Staffers from Beijing’s Liaison Office here have been following their progress for years.

Also, representatives of Hong Kong-based mainland organisations have been added to bolster their local counterparts. All these are in addition to the main pro-Beijing Federation of Trade Unions and the Democratic Alliance political party. Both are Hong Kong’s largest such civic organisations.

The five sectors of the Election Committee have 300 members each:

- Sector One: business, industry, finance — the local tycoons and their newly-added mainland counterparts.

- Sector Two: “white collar” professionals, including technology, engineering, architecture and surveying, accountancy, law, education, sports, health, social welfare.

- Sector Three: “grassroots” including labour, agricultural and fisheries, religion, hometown associations with mainland links, and other local groups.

- Sector Four: all incumbent legislative councillors, plus representatives of Hong Kong’s original inhabitants from the Heung Yee Kuk (Rural Consultative Council), district-level groups for fire and crime prevention, and representatives of Hongkongers now resident on the mainland.

- Sector Five: Hong Kong representatives in official mainland bodies including the National People’s Congress and the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

The new arrangements also include an increase in the size of LegCo from 70 to 90 members. But those seats directly elected on a one-person-one-vote basis have been reduced to only 20.

The old 70-seat council included 35 directly elected seats, plus five of the so-called “super seats.” Nomination for the latter was restricted but voting proceeded on a one-person, one-vote basis.

The powers of Hong Kong’s legislature are limited by Basic Law design. It is mainly responsible for passing or rejecting and amending government initiatives including its budget.

The Legislative Council election was to have been held a year ago, in September 2020, but will now be held this coming December 19.

Finally, the selection formalities for the next Chief Executive term, 2022-27, will be held on schedule on March 27, 2022.

The new vetting mechanism

Under the pre-2021 system, candidates’ eligibility was reviewed by civil servants seconded from their regular work to do temporary election duty. They are still known, British style, as returning officers who are responsible for keeping everything in order. But the old ways are already a forgotten memory. The new Candidate Eligibility Review Committee is a formidable thing and electioneering is no longer for fun.

Announced in early July, committee members are a mix of officials and non-officials, all with a strong national security component. Heading the committee is John Lee, previously Hong Kong’s Secretary for Security, before the government reshuffle in June.

Lee’s previous experience was in law enforcement until he was promoted from head of the Security Bureau to become number two in the Hong Kong government hierarchy as Chief Secretary for Administration. Police Chief Chris Tang moved up to head the Security Bureau. Both are known as no-nonsense law-and-order men.

Besides Lee and Tang, the vetting committee members are: Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Secretary Erick Tsang and Home Affairs Secretary Casper Tsui.

Three long-standing pro-Beijing loyalists round out the committee’s membership. They include: a former head of the Justice Department, Elsie Leung; and a former leading official, Rita Fan. She broke with Governor Patten over his 1990s political reform ideas and never looked back. Laurence Lau, a former head of the Chinese University, rounds out the committee.

Their decisions up or down to approve candidate eligibility are based on clearance from the new national security unit of Hong Kong’s police force, with oversight by the new Committee for Safeguarding National Security. This last is chaired by Chief Executive Carrie Lam with Beijing’s Liaison Office director Luo Huining sitting in as adviser.

Given the nature of this line-up, not many hold-over democrats are seeking admission to the new Election Committee. One who did is Cheng Chung-tai, a loner among them who did not resign in protest last November along with almost all the other incumbent pro-democracy legislative councillors.

Chung would have been joining the Election Committee automatically as an ex officio member of its fourth sector since he was a legislator. To solve that problem, he was summarily disqualified and dismissed as a legislative councillor, with immediate effect and no possibility of appeal.

The Hong Kong government is now authorised to take such summary dismissal action by reason of the central government’s decision last November, which specifically targeted misbehaving legislators. It was this decision that precipitated the protest resignations of Cheng’s colleagues.

In explaining the disqualification, Chief Secretary John Lee said Cheng’s credentials had been scrutinised by national security officials who decided he is not fit to occupy a seat on the Election Committee. Lee said the review committee would not be misled by those who use fine words to mask their true meaning. Cheng was thus deemed politically unfit, insincere, and only pretending to be loyal to the Basic Law, as officially defined, when in fact he is not.

Cheng’s group, Civic Passion, was one of the toughest survivors of the new post-2014 localist trend. None of its adherents tried too hard to hide their differences with other democrats. But Civic Passion was especially defiant in rejecting the perpetual plea for candidate coordination. Ultimately, they were left with only one victor in the last, 2016, LegCo election.

Perhaps Cheng stayed behind after all the others departed last November as one last act of localist defiance, and in order to use his hefty pay packet to help support the group. Civic Passion disbanded soon after his disqualification was announced.

A new election committee in the making

Cheng Chung-tai’s disqualification was announced on August 26, along with the results of the Candidate Eligibility Review Committee’s work. There are three types of candidates for the 1,500-member Election Committee with its five sectors and 40 subsectors.

The ex officio seats are not contested but reserved for specific officials. These include all the remaining legislative councillors — only 42 from the original complement of 70 – and all members of Hong Kong’s National People’s Congress delegation.

Additionally, designated bodies are allowed to nominate directly or in effect to appoint individuals to represent them on the committee.

Finally, some sectors allow individual voters to select candidates of their choice. In this way, the seats of the first two categories have already been filled, as reflected in the announcement of those who emerged unscathed from the Eligibility Committee vetting process. Sunday’s election concerns only those in the third category.

According to the August 26 announcement, there were a total of 1,015 validly nominated candidates. But of those, only 412 would be involved in the election since only 13 of the 40 subsectors have more than one candidate.

Voting in 23 subsectors will not be necessary due to the lack of competitors and 603 candidates will thus be returned uncontested.

The official summing up, according to the August 26 announcement: Of the 1,500 Election Committee seats, 325 individuals were validly approved as ex-officio members; 156 were validly nominated by designated bodies; 603 approved candidates were in uncontested subsectors. Thus, only 412 candidates are vying on Sunday for the remaining 364 seats.

There are currently 52 vacancies on the Election Committee which will not be filled on Sunday, mainly because the membership of LegCo is under strength at present, according to a press release.

According to the most recent calculations, cited in the South China Morning Post on September 17, the 364 seats in 13 of the committee’s 40 subsectors will involve only 4,889 voters. In the Election Committee subsectors poll five years ago, there were 232,915 voters who cast their ballots for a total of 748 seats.

Politicking under national security rule

In years past, Hong Kong reformers conjured up the term “rotten boroughs” to describe the Election Committee’s convoluted small-circle designs. It was a term used by 19th century democracy campaigners in England who finally brought about the Reform Act of 1832.

Reformers here ultimately abandoned their effort to re-think the Election Committee’s designs after deciding it was un-reformable. Better to concentrate directly on the campaign for “genuine” universal suffrage elections.

Then, after the reform drive of 2014-15 hit the brick wall of Beijing’s refusal to allow such elections, reformers concentrated on trying to win as many seats as possible on the Election Committee. They could at least try to influence the choice of Chief Executive in that limited way, from the sectors where democrats had greatest representation.

Sectors where democrats dominated were: Education, Legal, Accounting, Health Services, Social Welfare, and Information Technology.

One of the points which reform activist Benny Tai made was that democrats should aim to win as many seats as possible in the 2019 District Councils election since councillors were allocated seats on the Chief Executive Election Committee. That subsector has been eliminated in the general overhaul.

Now a new election cycle is underway and the closest thing to a forward-looking reform effort in this cycle actually came from Beijing. Officials let it be known that in Sector One, where big business dominates, seats should be rationed to no more than two per family. The business conglomerates and cartels they operate include more than one company, each often headed by members of the same family who have been able to claim separate company representation on the Election Committee.

A few optimistic pundits speculated about the tycoons being deprived of their old “kingmaker” status. They have apparently been a key element in Beijing’s final choice of Chief Executive candidates. Now Beijing aims to address the concerns of the new grassroots subsectors with all their groups and associations. Housing is a perennial issue. And the biggest property developers are represented on the Election Committee. Perhaps they will finally be pressed into action.

At the other end of the political spectrum, the losers in this exercise have at least been able to find some humour in the proceedings. Before Election Day some of Hong Kong’s biggest official names were seen out on the streets distributing fliers and greeting passers-by. Official word has it that direct face-to-face contact with citizens is necessary to try and drum up public enthusiasm for the proceedings.

But the officials with their kerbside stalls were on democrats’ turf, where there is little enthusiasm for anything associated with the new order. Unlike five years ago when over 300 democrats vied for positions on the Election Committee, this year the number is only three.

Best known is centrist Tik Chi-yuen, a former member of the Democratic Party who disagreed with the party’s position in 2014-15 over the electoral reform controversy. The other two are a district councillor and a construction company owner.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.