The familiar sight and sound of Democratic Party flags and a pre-recorded loudhailer message seemed strangely out of place, and so did the single sidewalk stall set up on a windy Causeway Bay street corner. It was noon on Sunday April 11, and two volunteers were trying to catch the attention of passers by.

The centrepiece of their lonely fund-raising effort was a single collection box, among the first signs of ordinary political life coming from Hong Kong’s pro-democracy camp since the series of blows began to rain down last year on June 30.

That was the day Beijing promulgated Hong Kong’s new National Security Law. The street corner volunteers were part of the Democratic Party’s territory-wide raffle ticket fund-raising drive, to help defray its members’ legal fees and court costs.

Cast out

Since June 30, Hong Kong’s most promising pro-democracy talent has either fled overseas or been imprisoned, and their most prominent elders are under indictment on a multiplicity of charges.

But the coup de grace for Hong Kong’s democracy movement was only administered last month, on March 30, when the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) in Beijing approved a reform plan that drastically re-shapes Hong Kong’s election system. Paramount leader Xi Jinping signed the promulgation orders that same day.

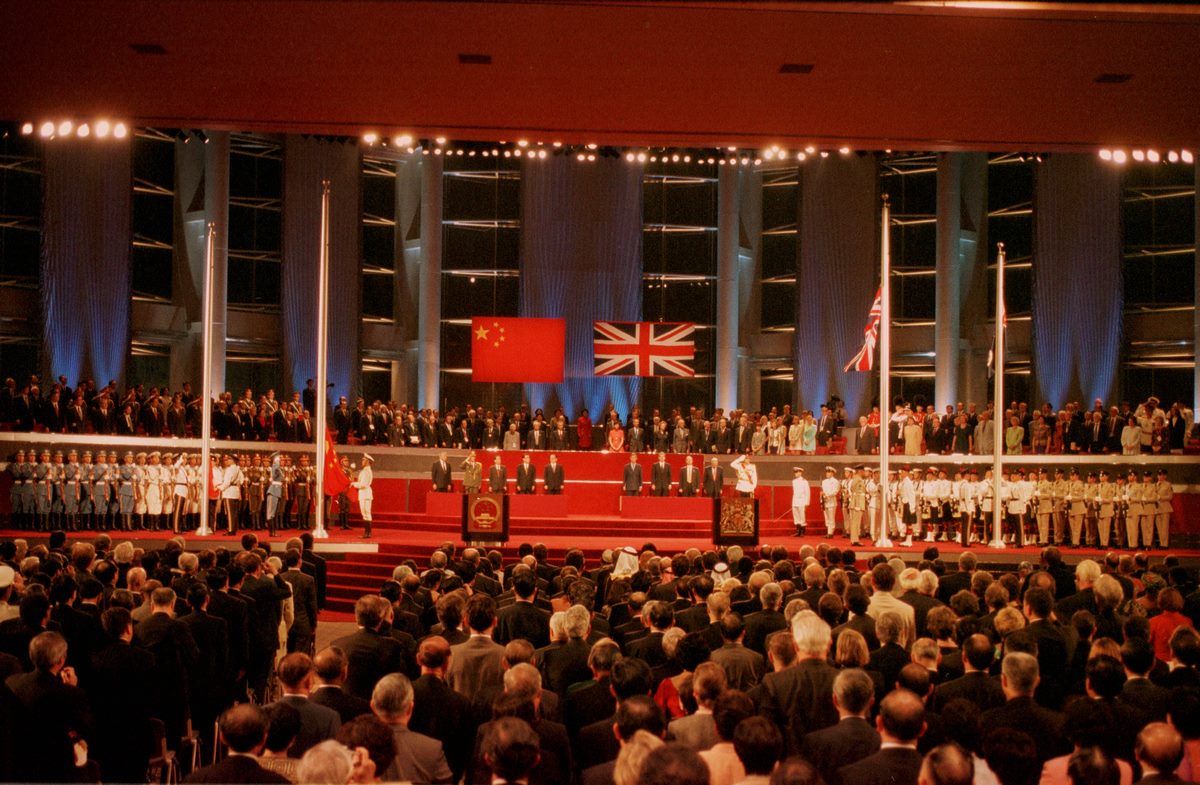

The new system replaces the old, that was spelled out in Hong Kong’s Basic Law constitution and has been in place since the former colony’s 1997 transfer from British back to Chinese rule.

Unlike its predecessor, however, the new system is devoid of loopholes and grey areas for determined politicians to try and exploit. Beijing commentators have taken to saying those promises were included specifically to help ease transitional 1997 fears and tensions, and need no longer signify.

Now, after two decades of endless controversy, all the original margins for manoeuvre are gone. The new system is specifically designed to disempower Hong Kong’s current generation of pro-democracy campaigners, who had built their movement on the promises of 1997.

Up until last summer, they had been campaigning to win a majority in Hong Kong’s 70-seat legislature. Henceforth, they will count themselves lucky to send a dozen members to represent — what had become — a majority of the Hong Kong electorate in the new enlarged 90-seat Legislative Council.

The next election was to have been held in September 2020. It was postponed to allow time for the sweeping overhaul and has just been re-scheduled for this coming December. The central government and party leaders in Beijing seem unperturbed by the message their new design conveys: if an election can’t be won, then cancel it and try again with a new system designed to guarantee victory forever more.

Perhaps to their credit, however, the new system is currently decreed for one election cycle only. Hong Kong government officials say they have received no instructions for what might follow.

The Democratic Paty’s April 11 fundraising effort seemed out of place not just because it was so isolated and forlorn, but because it brought back memories of times past. Until last summer, Sundays and public holidays were regular demonstration days and if protest marches didn’t assemble in nearby Victoria Park, they usually began at this point.

The one block in front of the old Daimaru Department Store building was turned into a pedestrian-precinct with fund-raising efforts all along both sides of the street.

On July 1 last year, the day after the new law’s promulgation and the 23rd anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule, holiday crowds gravitated instinctively to this same area and the adjacent intersection. But by then they had become an illegal assembly, gathering without police permission, and the first arrest of the new national security era occurred nearby as well.

An earlier time in the wilderness

If there is a way forward for the survivors of this assault, it is not immediately apparent. But some are old enough to remember a similar reversal of fortune 20 years ago, as well as some lessons about commitment and persistence that can be drawn from the experience.

The commitments were actually much weaker then, during the years just after Hong Kong’s 1997 return to Chinese rule. And the dangers were less clearly drawn than in recent years. There were also far fewer politicians and activists to stand as champions, and fewer voters to serve as the base line.

But Hong Kong’s democracy movement managed to survive a long period of drift — almost five years after the 1997 return to Chinese rule, or more specifically after 1998. During those years, the movement seemed to be wandering in the wilderness — rootless and directionless — as if everyone had lost sight of the forest for the trees.

At the time, it was difficult to explain and key players themselves were hard put to articulate what was happening to their movement. The Democratic Party is still the largest of many pro-democracy groups, but back then, in the early 2000s, it was the dominant player. Yet leaders Martin Lee and Lee Wing-tat could only give vague answers when asked why their movement had all but disappeared.

On occasion, they even admitted to becoming photo-op politicians, reduced to staging some small protest events just to attract the attention of a few press photographers. That was about as much attention as pre-1997 firebrand Emily Lau received in February 2002, when she and a few others staged a 30-hour hunger strike at the Hong Kong Island Star Ferry Pier.

They were calling for universal suffrage elections and protesting the undemocratic second-term appointment of Hong Kong’s first post-1997 Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa.

Momentum and enthusiasm had risen steadily during the 1990s, marked by the pro-democracy landslide victory in 1991. That was the year universal suffrage was allowed for the first time ever, to elect seats in Hong Kong’s colonial Legislative Council.

The council then had 60 members in total, of which 18 seats were opened up to direct election. The system’s designers assumed that the “right sort” of people would find it too undignified to stand on street corners campaigning for votes. That was the consideration behind the idea of carving the city into nine voting districts, with two seats per constituency and each voter allowed two votes.

The aim was to try and ensure that old-time traditional conservatives and pro-Beijing loyalists would have a candidate to choose in each constituency. The British authorities and their conservative Chinese advisers worried that candidates and voters alike would be put off by the brash new pro-democracy style of campaigning.

Instead, democrats won in a landslide, sweeping all but two of the 18 directly elected seats. Besides those 18, the others in the 60-seat council were filled by a few colonial-style appointees and new-style “functional constituencies.” These latter were the occupation-based “small circle” electorates first introduced on an experimental basis in the mid-1980s.

After 1997, Beijing was adamant about purging Hong Kong’s new election system of all the improvements introduced by Hong Kong’s last British governor, Christopher Patten, during his 1992-97 term of office. Rather than the “through train” arrangement that had been planned to carry the last colonial Legislative Council across the 1997 finish line, to become the first post-colonial council, Beijing declared that a new election must be held.

The 1998 exercise was conducted in strict accordance with Beijing’s original pre-determined format as spelled out in Hong Kong’s new Basic Law constitution, with the Functional Constituencies restored to their original “small circle” intent.

Some even followed the practice of corporate voting whereby company directors could cast votes allocated to a sub-sector, rather than allow employees to participate in the exercise as individuals.

Pro-democracy candidates nevertheless held their ground in that 1998 election. Voters turned out in driving rain on Election Day, May 24, to ensure that their pre-1997 candidates could carry on afterward. The turnout rate was 53% of a record 2.79 million registered voters, far above the first experimental universal suffrage elections in 1991 and 1995.

But then suddenly interest collapsed. Patten was gone. The historic 1997 handover date that had driven the movement since the early 1980s, had also come and gone. And a totally unanticipated intervention appeared almost immediately after July 1, 1997, in the form of the Asian financial crisis. With it came a multiplicity of economic questions giving Functional Constituency business types the edge in all debates.

The Democratic Party began to lose its most dynamic members. They dismissed the new post-1997 Legislative Council as a “debating club,” not at all what they had hoped to be part of during the heady days before 1997. Better we take our message to the streets than try to play the game in Hong Kong’s new style “birdcage democracy,” said the party’s “Young Turks” as they headed for the exit.

The revival actually began in 2002, but at the time attracted little more attention than Emily Lau’s hunger strike. Two groups were formed that same year, all dedicated in different ways to reviving the 1980s drive for democratic development and universal suffrage elections. Both had a lasting impact and as a tribute to their success, both are now under siege.

In 2002, they planned to work in ordinary ways through schools, churches, and the media, to counter what seemed to be an instinctive return to the old colonial way of life. Along with it came the growing idea that after all was said and done, democracy and politics were unnecessary distractions.

Power for Democracy was organised and led by academic Joseph Cheng Yu-shek, whose specialty became candidate-coordination. He and the group worked with more patience than most others could muster, to try and overcome what seemed to be an instinctive habit among aspiring democratic politicians. They could never resist competing against each other at election time.

The ultimate success of candidate coordination came in November 2019 with the landslide District Councils election and then in July 2020. Power for Democracy helped organize the informal primary election that democrats went ahead with, in early July, just days after the June 30 promulgation of the National Security Law.

Their straw poll exercise was designed to do what the group had always done, by helping to winnow the democratic field of candidates ahead of the Legislative Council election originally scheduled for September last year. But Cheng himself was not on hand to take a bow. He had just activated his old Australian passport and departed for Australia.

Almost everyone else associated with the primary exercise, having been denied bail, is currently in jail. They were arrested in January this year and are accused of subverting state power under the new National Security Law, for organizing and participating in the July primary exercise. Power for Democracy disbanded in February this year.

The second even more successful group organized in 2002 was the Civil Human Rights Front. It began by focusing on the Tung Chee-hwa administration’s drive to pass national security legislation as mandated by Article 23 of Hong Kong’s Basic Law constitution.

The front’s most spectacular success was the July 1, 2003 march, when half a million people unexpectedly came out in an angry but peaceful protest against the proposed legislation. The bill was shelved as a result and the Front became known for its skill in bringing many diverse groups together for the protest marches that became standard features of Hong Kong’s democracy movement.

According to a recent March 15 report in the state-run Global Times, the Civil Human Rights Front will soon go the way of Power for Democracy. Some 40 affiliated groups and parties have already announced their decision to disassociate themselves from the Front and its work.

These decisions follow reports that the Hong Kong government is investigating the CHRF for violating the new National Security Law by colluding with foreign forces. The allegations involve grants awarded by the United States government-funded National Endowment for Democracy.

Also contributing to the 2002-03 revival was the Article 23 Concern Group. Led by lawyers Audrey Eu and Margaret Ng, the group translated the legalistic prose into simple everyday language and produced a series of bilingual pamphlets explaining the crimes and dangers inherent in the proposed national security legislation.

The group then became the nucleus of the Civic Party organized in 2006. Several of the party’s members are currently among those arrested for participating in the July 2020 informal primary exercise.

One of their strongest legislators was Dennis Kwok. Like Joseph Cheng, his whereabouts only become known months after he and his family joined the Hong Kong diaspora and relocated, in his case to Canada.

Is there a way forward?

In such a climate, thoughts of a comeback similar to the 2002-03 revival seem as futile as the original dream of “genuine” universal suffrage elections. The challenge now is survival — for individuals, groups, and the movement itself. Such questions can’t be answered overnight.

But the coming elections, to be held under the new revamped system announced on March 30, are adding a sense of urgency to the gloom. Decisions must be made soon about whether to participate and how. Long-term planning can only take shape afterward.

The elections include an elaborate procedure scheduled for this coming September, to produce the Election Committee, centerpiece of the new system. Next will come the delayed Legislative Council election now re-scheduled for December, with the Chief Executive selection process following in March 2022.

Forthright as always, Emily Lau has set the pace. The details of her career are well known. Having moved on from her radical days — when she lambasted the British for selling out Hong Kong and, in 1991, became the first woman to win a directly elected seat in the Legislative Council — Lau joined the Democratic Party in 2008. She now holds forth as the doyenne of the democracy movement.

During online media interviews soon after Beijing promulgated the details of the revamped election system on March 30, Lau warned pro-democracy candidates to think carefully before trying their luck under the new system.

In the post-1997 past, she said, there were restrictions, but the vote was essentially open, free, and fair. Now she saw potential traps everywhere for candidates who might say too much, or make a wrong move, and for everyone associated with their campaigns as well.

Candidates would also have to undergo the “humiliating” exercise of seeking nomination signatures from all five sectors of the newly revamped Election Committee. That meant pro-democracy candidates could not avoid seeking endorsement from pro-Beijing loyalists.

But candidates could not relax even then, even if elected, since the new rules mandate continuing surveillance of legislators’ behavior throughout their tenure. This is to ensure they remain on the straight and narrow and do not violate the new national security norms, which have yet to be clearly spelled out so people can at least know what is acceptable and what is not.

Additionally, according to an Apple Daily account published on April 6, she also said she still believed in maintaining contact with Beijing, as the Democratic Party had done during their controversial 2010 meetings over a semi-successful electoral reform measure.

And democrats should still continue to strive for democracy. But they should carry on from outside the Legislative Council, not within. The current situation is grim, she said, but the struggle must not stop.

The Civic Party’s experience provides a sharper view of the bleak prospects democrats face. The party’s original aim was to contest elections and try to win as many seats as possible in the Legislative Council where its members could have the greatest political impact. With that option now all but closed, the party’s remaining members — many have already resigned — decided after much soul-searching to reorient their work and carry on as best they can.

A sad letter written by four of its members from their prison cells nevertheless illustrated the dilemma they all face. The four are lawyer Alvin Yeung, medical doctor Kwok Ka-ki, former Cathay Pacific Airline pilot Jeremy Tam, and a District Councilor, Lee Yue-shun.

Yeung, Kwok, and Tam were Legislative Councilors until the disqualification-resignation wave struck last November. All four were then among those arrested in January for joining the informal primary election last summer. All but Lee have been denied bail and remain in custody, awaiting trials that are yet to be scheduled.

In their letter, dated April 15, they said they had given up all hope of a future in politics and planned to disappear into the crowd of ordinary citizens going about their daily lives in other fields of endeavour. In effect, they are planning a return to Hong Kong’s old colonial way of life just as many did after 1998.

Understandably despondent given their situation, they nevertheless went on to commend their decision to all other party members as well, saying the dangers were now too great and the prospect of any reward too remote to warrant the risks involved.

It may sound brave and glorious to say you are willing to go to jail for your beliefs, they suggested. But actually being in jail is something else again. Disagreeing with the party’s recent decision to carry on, the four recommended that it should disband to spare everyone the endless prospect of disqualification and defeat.

Probably, given the history of this movement, many will be more inclined to follow the course recommended by Emily Lau and the Civic Party’s remaining core members. If one way doesn’t work, try another, they say.

But for those who have decided to remain, their next decision will be even more difficult — whether to remain active members of civil society but not within the political arena, or whether to join the new political order.

The risks are comparable either way. Even as active outsiders, they will be under constant scrutiny, looking over their shoulders, wondering who is following and watching and reporting back, and what the consequences might be. But if they try to join the new order in any capacity, they will likely have to follow in the footsteps of Anthony Cheung Bing-liang and Ronny Tong Ka-wah.

Cheung was among the first generation of committed democrats along with Martin Lee and Szeto Wah. But he left the Democratic Party, in 2004, returned to academic life, and later joined the administration of superpatriot CY Leung.

A lawyer by profession, Ronny Tong began his political career as a founding member of the Civic Party in 2006 but left the party in 2015. Two years later, he joined the administration of Chief Executive Carrie Lam to become a member of her advisory Executive Council.

Except for occasional moderating commentaries, neither man has contributed openly to any of the causes they once espoused. Nor have they emerged as role models, pioneering a middle-of-the-road centrist path that other pro-democracy partisans have been willing to follow.

Nevertheless, the struggle is continuing, almost as if it cannot be otherwise. Peaceful protests have become part of Hong Kong’s political heritage and should be allowed to continue, say the pundits.

Towards that end, members of the old Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China have stepped forward to try and carry on the tradition. Right on schedule, they have just applied for police permission to hold the annual Victoria Park vigil, which commemorates those killed in the military crackdown in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989.

Last year was the first in all the time since then that police permission was not granted for the June Fourth memorial vigil. The National Security law had been announced but was not yet promulgated. Permission was denied on health grounds due to the pandemic. But thousands congregated at the usual gathering place on the soccer pitches in Victoria Park. They lit their candles in silence, without the usual ceremonies, and the police stood back.

The prospects this year are even less bright. The current convenor of the Alliance, long-time labour activist Lee Cheuk-yan, has just been tried, found guilty, and sentenced to a total of 14 months in prison for helping to organise two illegal protest marches. One was on August 18, 2019, the other on August 31. His co-defendants in the first case included Martin Lee and Margaret Ng. Still, there is a chance.

Not by coincidence, a current Beijing pundit-of-choice, Tien Feilong, recently held forth on the issue. According to an Apil 5 account in Ming Pao daily, Tien provided a useful quote. The commemoration of historical events is legal, he said. But calling for the downfall of dictatorship is not.

One of the controversial slogans always used during the June 4 vigil ceremonies is “end one-party dictatorship.” A vigil without the slogan, perhaps?

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.