Hong Kong has long been renowned for its huge fiscal reserves and prudence in public spending.

Ahead of the Covid-19 pandemic, in January 2020, the government had nearly HK$1.2 trillion in fiscal reserves, the equivalent of 22 months of public expenditure. It had recorded 15 years of budget surpluses before the economy was hit by the 2019 pro-democracy protests and unrest and then by Covid.

By March, the reserves had shrunk to an estimated HK$817.3 billion – meaning that over HK$300 billion had drained away in just three years.

The ramifications for future government policies remain unclear. For this year, Financial Secretary Paul Chan proposed to maintain “zero-growth” in the civil service workforce and make no change to the profit and salary tax rates.

Chan disclosed hours after he introduced the 2023-24 budget that he had considered raising both taxes but “the timing is not right.”

In addition to the sharp drop in the reserves, the city has recorded rare budget deficits after many years of surpluses.

While there was a surplus of HK$29.4 billion in 2021-22, the shortfall was over HK$233 billion in 2020-21 and HK$140 billion in 2022-23.

Taking into account the proceeds from government bonds of about HK$65 billion, the forecast deficit for 2023-24 is HK$54.4 billion.

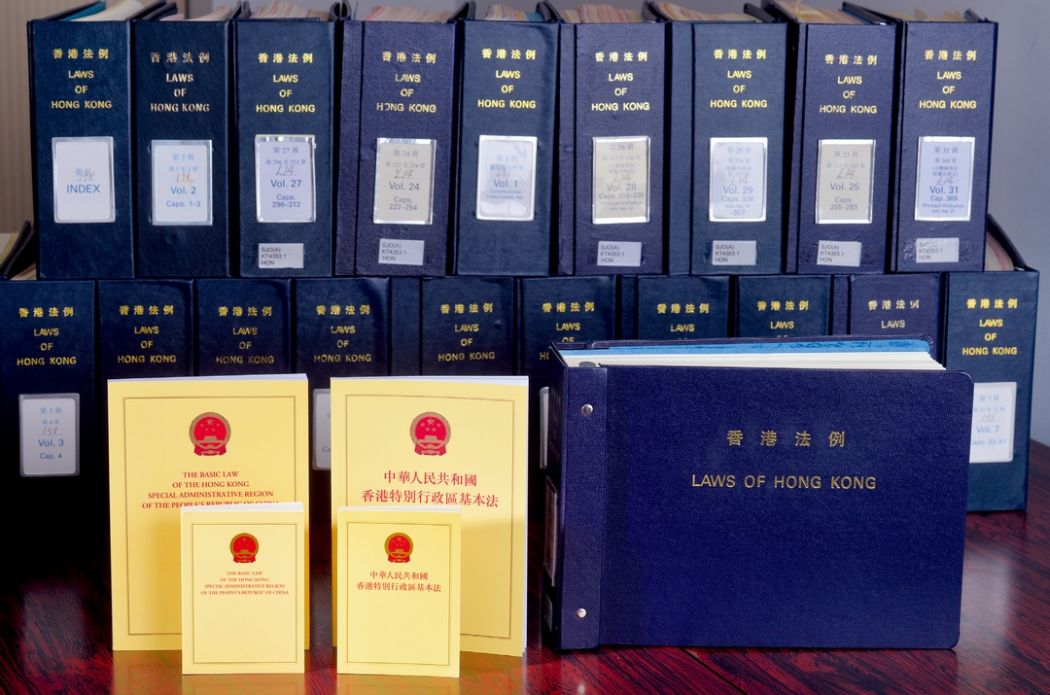

Balanced budgets are not just a desired fiscal policy but an obligation under the Basic Law constitution which came into force after the 1997 handover.

Article 107 says Hong Kong “shall follow the principle of keeping the expenditure within the limits of revenues in drawing up its budget.”

The government shall “strive to achieve a fiscal balance, avoid deficits and keep the budget commensurate with the growth rate of its gross domestic product (GDP).”

The Basic Law requirement

The principles of sound budgeting and minimal intervention in the private sector date back to British colonial rule.

Sir Philip Haddon-Cave, who was financial secretary from 1971-81, introduced the idea of “positive non-interventionism.” This recognised that the government had a responsibility to intervene in the operation of market forces, but within a limited scope.

The prudent fiscal philosophy was passed on to Hong Kong’s future rulers. The first public draft of the Basic Law published in April 1988 proposed tighter controls over the public finances than those later accepted.

The draft called for the city to “measure expenditure by revenues” when planning its budget.

It proposed a “basic balance” between revenue and spending, with growth in either not to exceed the rate of growth in gross domestic product “over a number of fiscal years taken as a whole.”

However, the proposal came under fire from the business sector for putting the Hong Kong government “in a straitjacket.”

The Business and Professional Group of the Basic Law Consultative Committee raised the issue that only one balanced budget had been tabled to the legislature between 1946 and 1988, whereas 21 budgets predicted a deficit and 20 a surplus.

It added that it would be “virtually impossible” for the authorities to draw up the budget based on GDP, as there would at least a two-year time gap between published GDP data and the government’s fiscal proposals.

During the public consultation period that followed, there were also requests for clarifications on what was meant by “measuring expenditure by revenue.”

The final draft of the Basic Law used more flexible wording, allowing future post-Handover administrations to introduce their own interpretations.

Terence Chong, executive director of the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Lau Chor Tak Institute of Global Economics and Finance, told HKFP that the constitutional restriction was decided during negotiations between Britain and China in the 1980s.

“It is to prevent Hong Kong from making overly large expenditures… to the extent that it does not know how to repay,” said the associate professor.

How much has changed?

The four post-Handover financial secretaries preceding Chan – Donald Tsang, Antony Leung, Henry Tang and John Tsang – used different wording to describe their fiscal measures but all defended the minimal intervention approach.

After public expenditure rose to 22 per cent of GDP in 2001-02, the then financial chief Antony Leung announced in his 2002-03 budget that the government’s target was containing spending to 20 per cent of GDP or below in five years.

“The growing share of public expenditure in the economy consumes scarce resources that could otherwise be used by the private sector more efficiently,” Leung told the legislature at that time.

The idea of keeping public spending under the 20 per cent threshold persisted until Carrie Lam took office as chief executive in 2017, pledging a “new fiscal philosophy.”

Chan announced in the 2018-19 budget that public spending would be “slightly higher than 21 per cent of our GDP” in subsequent years, “in the face of various development needs of society and the economy.”

But even with the increase in public spending, Chan maintained a surplus until the city was hit by the 2019 pro-democracy protests and unrest and the start of the Covid pandemic the following year.

Why is Hong Kong so prudent?

Apart from the constitutional constraints, Chong said Hong Kong’s economic structure also caused the government to strive to avoid budget deficits.

While other developed economies such as the UK, the US and Japan could tolerate debts almost equal to or even double their GDP, Hong Kong lacked the means to repay such a sum.

Currently the Hong Kong government’s outstanding debts only account for four per cent of GDP, whereas data by the World Economics Research show that regional rival Singapore had a debt-to-GDP ratio of 127.8 per cent.

“As Hong Kong is not a sovereign state, it cannot print money to repay debts,” Chong said.

Higher taxes were also not an option. Chong said Hong Kong’s wealth was mainly derived from capital outside the city through finance and entrepôt trade, instead of local business activities or natural resources.

“To a large extent, we depends on outsiders to bring money to us. There is no reason to raise taxes and drive your guests away,” he said.

Why is our book in the red?

Presenting his latest budget, Chan said the decline in revenue from tax incomes and land sales, as well as “huge expenditure” on Covid, were the main reasons for the red ink.

He said the city had spent over HK$600 billion in anti-epidemic and relief measures over the past few years.

Chong agreed with the financial secretary that the budget deficits were mainly due to the pandemic.

“The most important issue is whether you can cut back the amount you previously spent,” the professor said, adding that government spending on healthcare had ballooned in the past two years and accounted for 20 per cent of its recurrent expenditure.

Chong said that as long as the authorities could cut back special funding to public hospitals instated during the pandemic, the deficits would not be structural.

He said the government’s options were limited if it wanted to raise tax income. An increase in salaries tax “would not be of much help” as that was not the main source of revenue, whereas increasing profits tax might drive businesses away from Hong Kong.

Revenue from land sales and the current profits tax would recover in line with the economy.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

Original reporting on HKFP is backed by our monthly contributors.

Almost 1,000 monthly donors make HKFP possible. Each contributes an average of HK$200/month to support our award-winning original reporting, keeping the city’s only independent English-language outlet free-to-access for all. Three reasons to join us:

- 🔎 Transparent & efficient: As a non-profit, we are externally audited each year, publishing our income/outgoings annually, as the city’s most transparent news outlet.

- 🔒 Accurate & accountable: Our reporting is governed by a comprehensive Ethics Code. We are 100% independent, and not answerable to any tycoon, mainland owners or shareholders. Check out our latest Annual Report, and help support press freedom.

- 💰 It’s fast, secure & easy: We accept most payment methods – cancel anytime, and receive a free tote bag and pen if you contribute HK$150/month or more.

MORE Original Reporting

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.