“No stone left unturned” should be the hallmark for Hong Kong’s new life under national security rule which began almost five months ago on July 1, the anniversary of the city’s 1997 return to China.

The new order began with the central government’s promulgation of a mainland-style national security law late on June 30. It is being enforced in multiple ways, including formal court proceedings and the decisions of officials both here and in Beijing.

Their reach is all-encompassing. Nothing seems to be off limits, not Hong Kong’s heretofore independent judiciary and certainly not its legislature, which has suffered the severest blow.

Gaining further momentum, the “rectification” campaign has now been extended even to Hong Kong’s Basic Law. This seems inevitable: the new legislation is being enforced in ways that directly contravene post-colonial Hong Kong’s most basic legal safeguards.

The original guarantees

The Basic Law was drafted under Beijing’s supervision and promulgated in 1990, to serve as Hong Kong’s constitution after 1997. It also reflected much of the intent negotiated beforehand and written into the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, which spelt out the terms of Hong Kong’s transfer from British to Chinese rule.

When sceptics pointed out that the agreement which led to the declaration had no enforcement mechanisms, its British defenders said “no matter”. At least everything had been written down in plain language for all the world to see. Chinese leaders could be trusted to honour their word before such an audience.

Among the general principles included in the Joint Declaration were promises about the “high degree of autonomy” which post-1997 Hong Kong would enjoy — to include executive, legislative, and independent judicial power. The Chief Executive would be appointed by the central government in Beijing, but on the basis of elections or consultations in Hong Kong. Social and economic systems would remain unchanged, with all civil rights and freedoms to be ensured by law.

Beijing elaborated on the promises in Annexes to the Declaration. Accordingly, its promises would be written into a Basic Law to be used in governing Hong Kong after 1997. The legislature “shall be constituted by elections.” The executive authorities “shall be accountable to the legislature.” A Hong Kong prosecutorial authority “shall control criminal prosecutions free from any interference,” and much more.

Beijing kept its word. The new Basic Law constitution was promulgated in April 1990, less than a year after the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown that marked the end of China’s own democracy movement.

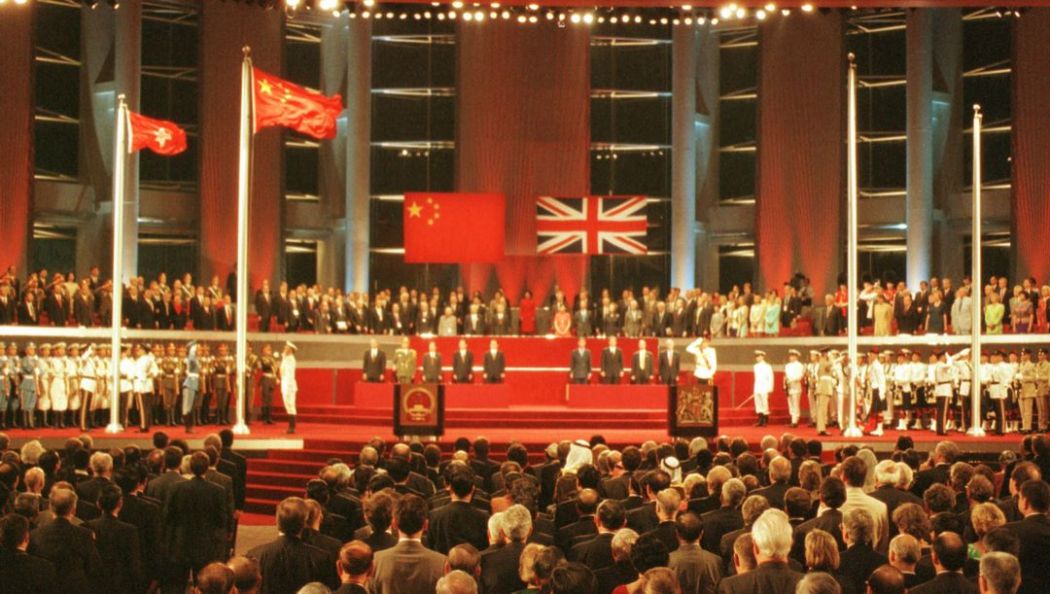

Nevertheless, Hong Kong’s new law contained all the promises outlined in the Joint Declaration and went into effect on July 1, 1997. It was advertised as “one-country, two-systems,” a phrase that became the standard reference for Hong Kong’s governing principles.

Thereafter, a new generation grew up memorising the promises and living by them. The pledges also motivated the growth of a democracy movement that set its goals and organised its campaigns to accommodate the Basic Law’s vague timetables. These promised “gradual and orderly” progress toward universal-suffrage elections for both the Chief Executive and the Legislative Council (Articles 45, 68). That progress could begin in 2007.

As 2007 drew near, Beijing issued a decision delaying the commencement date for another decade. Hong Kong’s first universal suffrage election for Chief Executive was tentatively scheduled for 2017. It was only during preparatory campaigning in 2014-15 that Beijing finally revealed what was meant by a universal suffrage election – one where it first determined the candidates.

Everyone essentially overlooked the Basic law’s Article 5, which contained a different kind of promise. It declared cryptically that “the socialist system and policies shall not be practised in Hong Kong” and “the previous capitalist system and way of life shall remain unchanged for 50 years.” There has never been any kind of explanation as to the meaning of Article 5.

Reformulating the Basic Law’s promises

In May this year, shortly before Beijing’s surprise announcement about the imminent National Security Law, former Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying posted a curious commentary on his blog site. At the time, it seemed like just another of his flippant putdowns of pro-democracy partisans and their foreign friends.

CY, as he is known, was Chief Executive between 2012 and 2017. He stepped down after only one term, ostensibly for personal reasons, but more likely because his abrasive personality was adding further tension to Hong Kong’s volatile political atmosphere.

Leung’s May 19 blog post was true to form. He presented his thoughts as a series of answers to questions from “alien” visitors who might arrive from outer space knowing nothing about the local form of government or Hong Kong’s relationship with its Motherland.

In retrospect, Leung was previewing some new formulations about the Basic Law’s promises, which must have been taking shape in Beijing while the National Security Law was being finalised. Or perhaps the ideas were not new and had only been kept under wraps in anticipation of future use.

But whatever the case, Leung was in effect introducing Beijing’s current thinking about the old Basic Law promises. Evidently those promises, as originally understood, are being airbrushed from the public record in deference to new formulations more to Beijing’s liking.

The immediate context of Leung’s literary intervention was a blast from Beijing in April, criticising pro-democracy legislators for filibustering and other delaying tactics in the Legislative Council. Critics pushed back, reminding Beijing of the Basic Law’s Article 22, which promised that no department of the central government would interfere in Hong Kong affairs.

Article 12 overrides all else, responded Beijing’s defenders. This says Hong Kong is directly under the central government in Beijing, suggesting that it can intervene directly in Hong Kong affairs. The people of Hong Kong are not sovereign, wrote Leung. He reminded his readers that Britain returned sovereignty to the central government in Beijing and not to the people of Hong Kong.

But that same Article 12 also grants Hong Kong autonomy. Leung did his best to explain the contradiction. Hong Kong did not have its own power before it was returned to China and was rechristened as a Special Administrative Region within the People’s Republic.

Therefore, all of Hong Kong’s power or autonomy was granted afterwards, by the central government and derives therefrom — it is Beijing’s to give and Beijing’s to take away.

Thus, executive, legislative, and judicial power in HK all derive from the same source, namely, the central government. There is no local power. In return, Hong Kong and its people are responsible for defending China’s sovereignty and national security.

Hong Kong does enjoy autonomy in terms of finances and local taxation. But even this local power, according to Leung’s reasoning, is enjoyed only because of the consent and support of the Chinese people, as administered by the central government.

Hong Kong’s system is executive-led because its government is made up of principal officials who are appointed both by the Chief Executive here and by the central government in Beijing.

It is true that Hong Kong’s executive-led government is accountable to the Hong Kong legislature. But that accountability is confined to only four limited areas.

One area is the implementation of laws passed by the Legislative Council, although such legislation cannot be initiated by the council itself. Also, the Chief Executive is required to present regular policy addresses to the Legislative Council, and to answer questions from legislators during question time. Finally, government budgets and taxation plans must be approved by the Legislative Council.

Powers are not separated. Nor were they under British rule. The judiciary is independent. But the relationship between the executive and legislature is not one of separated powers.

Under National Security rule

Leung Chun-ying’s musings were a preview of all that is now coming to pass. The National Security Law criminalises secession, subversion, terrorism — meaning political violence — and collusion with foreign powers for the purpose of interfering in Hong Kong affairs. The law is not retroactive.

To ensure proper implementation, a contingent of mainland public security officials took up residence here immediately after the law was promulgated. Beijing’s local Liaison Office representative now sits on the Chief Executive’s new advisory committee, and a group of Hong Kong judges have been especially designated by the Chief Executive to hear national security cases.

Still not satisfied, Beijing’s longstanding reservations about Hong Kong’s judiciary have turned into a frontal assault. Earlier complaints targeted local judges’ alleged penchant for molly-coddling political miscreants. Now there are calls for wholesale reforms that violate the most basic tenets of judicial independence.

Despite some serious pushback from within the judiciary itself and from legal professionals, the complainers are not retreating. Besides naming and attempting to shame individual judges whose rulings are giving the benefit of the doubt to too many of last year’s street protesters, there are now demands for standardised penalties in order to limit judges’ flexibility in sentencing.

Beyond these details of judicial administration is the campaign to include judicial reform as part of Beijing’s new focus on the Basic Law itself. Leung Chun-ying ‘s message to alien visitors pointed the way.

Zhang Xiaoming, deputy director of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office in Beijing, has again taken the lead. Zhang was the official whose remarks in June presented the National Security Law as something of a minor intrusion that would target only a “very few” misbehaving Hongkongers.

He addressed the current challenge directly in another online seminar, this one on November 17. In this presentation, Zhang referred to the Basic Law as a “living law,” meaning one that needs to be amplified and adapted over time with the addition of new legislation and interpretations.

Such interventions are needed to accommodate problems that have appeared during the past two decades of implementation, according to him. The aim is to ensure Hong Kong’s well-being during the next 26 years … a rare reference to the 50-year cutoff date mentioned in the Basic Law’s Article 5.

Zhang blamed misunderstandings and misconceptions about Hong Kong’s governing principles for recent troubles including last year’s street protests. All were the result of failure to comprehend the true nature of Hong Kong’s status as defined by the Basic Law — which according to him is nevertheless a work in constant motion as problems arise and solutions are sought.

The immediate context for his November 17 presentation was a new decision by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC). Issued on November 11, it re-set the qualifications for legislators and public officials in accordance with the National Security Law.

Hence, legislative councillors who promote or support the idea of Hong Kong independence, or who refuse to recognise China’s sovereignty over Hong Kong, or who seek interference by foreign forces, or commit other acts endangering national security — do not comply with the legal requirement to uphold the Basic Law.

The NPCSC ruling reinforces its 2016 decision that strengthened the provisions of Basic Law Article 104, on oath-taking. That decision precipitated the long-running oath-taking saga that continued through multiple court appeals but ultimately did what it was intended to do with the disqualification of six legislators. The November 11 decision short-circuits all the formalities and eliminates the possibility of court appeals.

The decision was also specific. It applied to current legislative councillors who had been ruled ineligible to stand as candidates in the election originally scheduled for September 6. The decision also applies to any future candidate or member of the Legislative Council. Sitting members may be summarily expelled without following the Basic Law’s stipulated procedure for removing legislators from office.

Under this procedure, the person must be censured for misbehaviour or breach of oath by a vote of two-thirds of the Legislative Council members present (Article 79).

Immediately after the November 11 NPCSC decision was issued, the Hong Kong government used its new authority to disqualify and expel four legislators, albeit for acts committed before the National Security Law went into effect on June 30.

The four had already been disqualified as prospective candidates for the next Legislative Council election, originally scheduled for September 6, before the poll was postponed on the grounds of coronavirus. The four had recanted their past actions but vetting officials disqualified them anyway on grounds their new declarations of loyalty were probably not sincere.

Zhang Xiaoming elaborated further, addressing three points that have inspired years of debate and controversy. Anti-China activism by legislators and public servants will not be tolerated, he stressed, reviving a statement from the 1980s attributed to the then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping.

Deng said many things, including other statements that seemed to contradict this one. But while the Basic Law drafting process was underway, he was quoted as saying that only patriots should govern Hong Kong. That qualification is now a legal requirement, said Zhang. Only patriots can govern Hong Kong. Anti-China activists need not apply.

Zhang also said the judiciary must be reformed because its rulings had put the wrong slant on Hong Kong’s Basic Law. Perhaps this followed from the common practice of considering precedents from other jurisdictions unrelated to China and its laws. Zhang cited retired Judge Henry Litton’s current drive for judicial reform and said officials were now working on plans for reforming Hong Kong’s judiciary.

Finally, Hong Kong’s Basic Law constitutional system must also be reformed — in order to replace misconceptions with correct principles inspired by patriotic love-of-country.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.