It was exactly six years ago that Benny Tai added an unexpected political spark to the Lunar New Year holiday by introducing a new plan to break the political deadlock.

He and his contemporaries had been agitating for democratic political reform since their college days in the 1980s, when Hong Kong was still a colony and universal suffrage was regarded as something too risky for the locals to handle.

By early 2013, reform-minded activists had tried everything… short of taking to the hills. But political violence had long been dismissed as totally unacceptable. Rallies and demonstrations remained always within the formal rules of public order.

Yet Hong Kong’s new national authorities in Beijing remained as reluctant as the British had always been before them to introduce direct universal suffrage elections. The idea of ordinary people electing their own government remained anathema despite the promises those same Beijing authorities had initially made to allow such elections once the British were gone.

Looking back: 2013-2014

Professor Benny Tai Yiu-ting from Hong Kong University’s Law School introduced his new idea in a series of articles published in the Chinese-language Hong Kong Economic Journal. He didn’t try to minimise the provocative effect.

The first article was titled “Civil Disobedience, the Most Lethal Weapon,” published on Jan. 16, 2013. Other articles followed on January 30, February 6 and 25. The timing was perfect… good for holiday reading… and within a month his idea had taken hold.

Civil disobedience or deliberate sustained defiance of public order rules and regulations, in the name of a just cause, had never been tried in Hong Kong before. He and two friends … Chinese University sociologist Chan Kin-man and the Reverend Chu Yiu-ming… and ultimately many others as well spent the next year explaining the idea and preparing for a peaceful three-day sit-in downtown that came to be known as Occupy Central.

The idea was to mobilize 10,000 people for the task of blocking an intersection in Hong Kong’s central business district if Beijing continued to procrastinate. But the larger aim was to focus the public’s attention on the importance of the cause and thus pressure Beijing to focus on the long-delayed goal as well.

The need for wider public understanding was an important goal. People and politicians were unused to thinking in terms of constitutional reform and democratic elections. Hong Kong had only just begun experimenting with the idea of allowing ordinary citizens to vote for their government leaders, which meant there was no tradition or experience and no precedent to guide the way forward.

The first direct election for a minority of seats in the Legislative Council did not occur until 1991. The 1992-1997 administration of Hong Kong’s last British governor, Christopher Patten, was the first real introduction Hong Kongers had to the dynamics of electoral politics. And for the Communist Party-led dictatorship in Beijing, the idea of an open free election was beyond the pale.

Nevertheless, the Basic Law constitution Beijing promulgated for Hong Kong following the Sino-British agreements promised such elections, in Articles 45 and 68, and a time-line had grown around them as a result of constant pressure from Hong Kong pro-democracy partisans unwilling to let the matter lapse.

Beijing had been making excuses and delaying from one manufactured deadline to the next, dating back to 1988, while the Basic Law was being drafted.

As of early 2013, the next possible date according to Beijing’s ambiguous promises was 2017, for the 2017-2022 term of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive. This meant the existing ponderous Chief Executive Selection Committee procedures would have to be changed well in advance, with a promised public consultation exercise in between.

The goal, according to Beijing’s timeline, was to achieve the promised election of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive by universal suffrage, in time for the 20th anniversary celebrations of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule. Legislative Council reforms were to parallel those for the Chief Executive.

But Beijing had also ruled that universal suffrage for the Chief Executive must precede such legislative elections in order to maintain the unbroken authority of Hong Kong’s “executive-led” government. This last was one colonial inheritance the new rulers were happy to endorse.

A new Chief Executive was sworn in on July 1, 2017, President Xi Jinping did fly in to officiate, and the ceremonies were very grand. Beijing and Hong Kong had also spent many months focusing intently on constitutional reform and so had the general public during the government’s formal consultation exercise as well as before and after. But nothing had gone according to anyone’s plan.

Beijing’s final decision was announced on August 31, 2014: everyone could vote in the 2017 Chief Executive election, but only for candidates approved by Beijing, and authorised by the existing ponderous committee procedures. These are designed to produce the desired results and make a mockery of the universal suffrage promise.

Worse still, the reform sequence to realise the promise of universal suffrage elections for Chief Executives would proceed no further but end at that point. Parallel reforms that were supposed to continue at the legislative level, to be finished in time for the 2020 election, fell by the wayside. Beijing’s 8.31 Decision dismissed them.

Benny Tai stunned supporters with his candid disclosure at the time that he considered his effort a failure. What he should have said was that the Occupy idea had failed to impress Beijing. As for Hong Kong’s political community, his campaign had only just begun.

The Occupy Central campaign had planned, hopefully, for 10,000 people to block a downtown intersection for three days. Instead, many times that number blockaded key thoroughfares throughout the city, set up tents, organised a whole new street-culture lifestyle, talked politics for hours on end, and carried on for 79 days.

During that time, Benny Tai watched while his campaign escalated far beyond his control and acquired a whole new identity, and a new name as well, to become known as the Umbrella Revolution.

The sudden escalation took shape after police fired volleys of teargas to disperse gathering crowds on that September 28 afternoon, and people in the direct line of fire had only their umbrellas for protection.

But in addition to the misguided crowd-control measures, a new leadership had emerged from among the younger student generation who were drawn to the challenge of electoral reform just as their elders had been before them. Elections and electoral democracy were, they all maintained, the best way to safeguard Hong Kong’s autonomy in all respects against Beijing’s growing inference.

University students stepped into the breach and called a protest classroom boycott that carried the campaign forward after Benny Tai seemed to falter in early September. The combination of student energy and the drive of Hong Kong’s long-standing protest-coordinators in the Civil Human Rights Front… responsible since 2003 for the annual July First protest marches… propelled the movement forward into the consciousness-raising event it ultimately became.

A year later that same spirit was still strong enough to sustain the sometimes-faltering resolve of Legislative Councillors, obliging them to stand by their pledges. The Hong Kong government’s political reform legislation, based in every detail on Beijing’s August 31 Decision, failed to win the necessary two-thirds majority vote in the Legislative Council.

The reform project that had sustained Hong Kong’s current Democracy Movement since its inception in the 1980s, had reached a dead end.

But the spirit of defiance lived on in a new generation of post-Occupy candidates who tried to do via the existing electoral possibilities what Benny Tai’s idealistic campaigning had failed to achieve from the streets.

The trial

Today the three friends… Tai, Chan, and Chu… are waiting to learn their fate after a month-long trial for their roles as co-founders of Occupy Central. The trial ended in mid-December last year. The verdict will be announced in April. They and six others active at different stages of the campaign have been singled out and charged as a group.

Now known as the “Umbrella Nine,” they are charged with conspiracy to provoke a public nuisance, inciting others to cause a public nuisance, and inciting people to incite others to cause a public nuisance. The charges carry a maximum sentence of seven years imprisonment.

Everyone knows Benny Tai may well be spending the next Lunar New Year holiday behind bars. But when he addressed the court at the end of the trial in mid-December, his final speech for the defence produced a standing ovation from supporters inside the courtroom and those listening outside as well… a spontaneous expression that court attendants did not try very hard to silence.

Professor Tai’s 30-minute oral submission explained the Democracy Movement’s predicament as he argued the case for civil disobedience and genuine universal suffrage elections, and for the right to peaceful demonstration.

“We have waited for more than 30 years for our constitutional rights,” he said. Yet “democracy is still nowhere in Hong Kong.” He cited the Basic Law’s unfulfilled promises as the justification for resort to civil disobedience on conscientious grounds in order to bring about change in unjust government policies.

He acknowledged his debt of inspiration to American civil rights leader Martin Luther King. Tai cited King’s defence of civil disobedience. He had asserted that holding a public protest demonstration against an unjust law without official permission… and then accepting punishment for such disobedience… was to show the highest regard for law and order.

All of that was especially true when there were also laws guaranteeing, as they do both in Hong Kong and in the US, freedom of speech and assembly and the right to demonstrate (HK Basic Law, Article 27).

Such disobedience was also a deliberate means of trying to arouse the conscience of the wider community over the injustice perceived by some but not necessarily recognised by all.

From Occupy to “Independence,” The Post-Occupy Election Candidates: 2015-2016

During the years prosecutors spent preparing to make their case against Benny Tai and his co-defendants, the spirit of the campaign lived on and adapted in ways they probably never anticipated. Although it was not immediately recognised as such at the time, the Lunar New Year holiday in 2016 marked another political milestone for Hong Kong’s Democracy Movement.

The key player, Edward Leung Tin-kei, has already begun his new life in Stanley Prison and, not satisfied with a six-year sentence, prosecutors are currently trying for more. The verdict in a second trial, just concluded, is yet to be announced. But if jurors could not easily find him guilty as charged, prosecutors had no difficulty looking for grounds because violence had been involved.

There was a scene in the locally-produced futuristic film “Ten Years,” where despondent young activists are discussing Hong Kong’s political fate. The year is 2025 and the film, released in December 2015, projected a dark view of Hong Kong 10 years hence when “mainlandisation” under Beijing-style draconian rule would be more-or-less complete.

All else having failed and not knowing what to do next, the friends speculate that maybe they had not fought hard enough to preserve Hong Kong’s autonomy and identity as a different Chinese place with a different way of life… different in too many ways from the rest of a China that was ruled by the national Communist Party-led government in Beijing.

There had been no liberation struggle and not a single life had yet been lost. This discussion sets the stage for a final protest self-immolation scene when one life is finally sacrificed.

The dark depressing low-budget experimental film was a surprise hit… probably because it reflected the post-Occupy political mood so well. Nothing had worked. People saw themselves as powerless to curb or contain mainlandisation, meaning the cross-border encroachment of people, policies, and ideas over which Hongkongers had no say.

Authorities in Beijing and Hong Kong had thumbed their noses at Occupy despite all its efforts to maintain the discipline of peaceful resistance.

By the winter of 2015-16, violence was in the air and reflecting that mood was a new group calling itself Hong Kong Indigenous in English or Local Democratic Front in Chinese. They were talking about violence and independence… in all but name. The terms they used were valiant struggle and genuine autonomy or self-determination.

HKU philosophy major Edward Leung Tin-kei was the group’s most articulate leader and figured prominently in the street violence that occurred in Hong Kong’s Mong Kok district overnight on February 8-9 at the start of the Lunar New Year holiday.

It was a localist event, dubbed the “Fish Ball Revolution” because it involved the defence of street hawkers who are often targeted by government inspection teams. Fish balls are a favourite fast-food snack. During the overnight confrontation with police, led by Leung’s group, some 200 people were injured including 90 police officers. Leung was among the 60 people arrested.

But the violence also served another purpose… as a campaign event to introduce candidate Edward Leung. He had already made enemies within the mainstream democratic camp by defying their candidate-coordination efforts. Leung was determined to stand in the coming special by-election as a means of introducing his ideas to the wider public.

Before Mong Kok, he was unknown. During the three-week election campaign afterward, he was able to explain himself so well that many people in his New Territories East constituency were willing to disregard their aversion to violence and reward him with 66,000 votes.

Luckily, there were still enough to save the Legislative Council seat for the other democratic candidate. Otherwise, mainstream “pan-democrats”… a term used to distinguish them from the many emerging variations on the “localist” theme… would never have forgiven him.

Edward Leung’s adventure set the stage for the general Legislative Council (LegCo) election later that year… the one that was supposed to have carried forward the reforms that would lead to something like full universal suffrage in 2020.

He was one of the most forthright champions of the localist cause. Its code words during the 2016 LegCo election campaign, and the lower-level District Councils election the year before, were self-determination and autonomy to be achieved via the ballot box if possible, but by other more “valiant” means if not.

Besides Edward Leung there were many others and many variations on the same theme. But at that time, during the 2016 election campaign, he was not the most daring. That accolade went to Andy Chan Ho-tin, an engineering graduate from Hong Kong’s Polytechnic University who had been an Occupy activist.

He reasoned that the quest for self-determination or autonomy was futile because Beijing would never allow any of that. So there was no point playing word games with definitions about what meant what. Marches and demonstrations and slogans were also useless.

He therefore advocated repudiating the Basic Law, as did others at that time. But unlike most of them he came out openly for independence, saying it was the only solution for Hong Kong’s predicament.

In March 2016, Chan announced the formation of a new political party dedicated to that end and called it the Hong Kong National Party.

He also agreed with Edward Leung that violence was acceptable when all else fails and invited Leung to be one of the featured speakers at an independence rally defiantly held in Tamar Park outside the Hong Kong government headquarters.

Despite the barrage of denunciations laid down against it, the new message was surprisingly well received. Out on the campaign trail, the new post-Occupy candidates were at first hesitant to betray their origins and commitments.

The candidates nevertheless did better than expected in the 2015 District Councils election, the February by-election that gave Edward Leung 66,000 votes, and finally in the Legislative Council election itself.

What probably alarmed Beijing the most, however, was the wider appeal. Not only did a handful of the “new” post-Occupy candidates actually win seats, but the popularity of the post-Occupy themes for self-determination and genuine autonomy was so great that all the “main” pan-democratic parties endorsed them as well.

The mainstream “traditional” pro-democracy parties including the Democratic party, the Civic Party, Labour Party, and even the moderate Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood, all endorsed the self-determination idea… without defining the term too carefully… ahead of the September 2016 election.

Self-determination was no longer a “radical” policy… except in official Beijing eyes. And therein lay the seeds of its downfall.

The long route from victory to defeat: 2016-2018

Strategists in Beijing must be congratulating themselves for a job well-done. From their perspective, the counterattack has been a masterful success: slow, steady, and relentless, administered by the Hong Kong government and judiciary with the principles of prosecutorial discretion and judicial deference ensuring the desired results based on Beijing’s directives… all accomplished in accordance with “the rule of law.”

By the time it was done, the entire “class” of new post-Occupy political talents had been removed from direct participation in government and everyone else, all the mainstream parties and players, had received the message as well.

The official pushback actually began before the 2016 election, with the introduction of a new confirmation form. It required prospective candidates to pledge allegiance to Hong Kong as a region under the authority of the national government in Beijing.

This had been a formality before. Now it became a matter to be vetted and verified by election officials. Edward Leung and Andy Chan were among the six hopefuls denied permission to contest the 2016 election, although the government didn’t get around to banning Chan’s Hong Kong National Party until mid-2018.

Immediately after the September, 2016 LegCo election, pro-democracy legislators organised an oath-taking protest for the swearing-in ceremony. It’s tempting to speculate what might have been had they not overplayed their hand. But the event provided Beijing with just the opportunity needed to put some real legal teeth in its counterattack.

Two of Edward Leung friends, Yau Wai-ching and Baggio Leung Chung-hang were the most aggressive and used to occasion to proclaim that “Hong Kong is not China.”

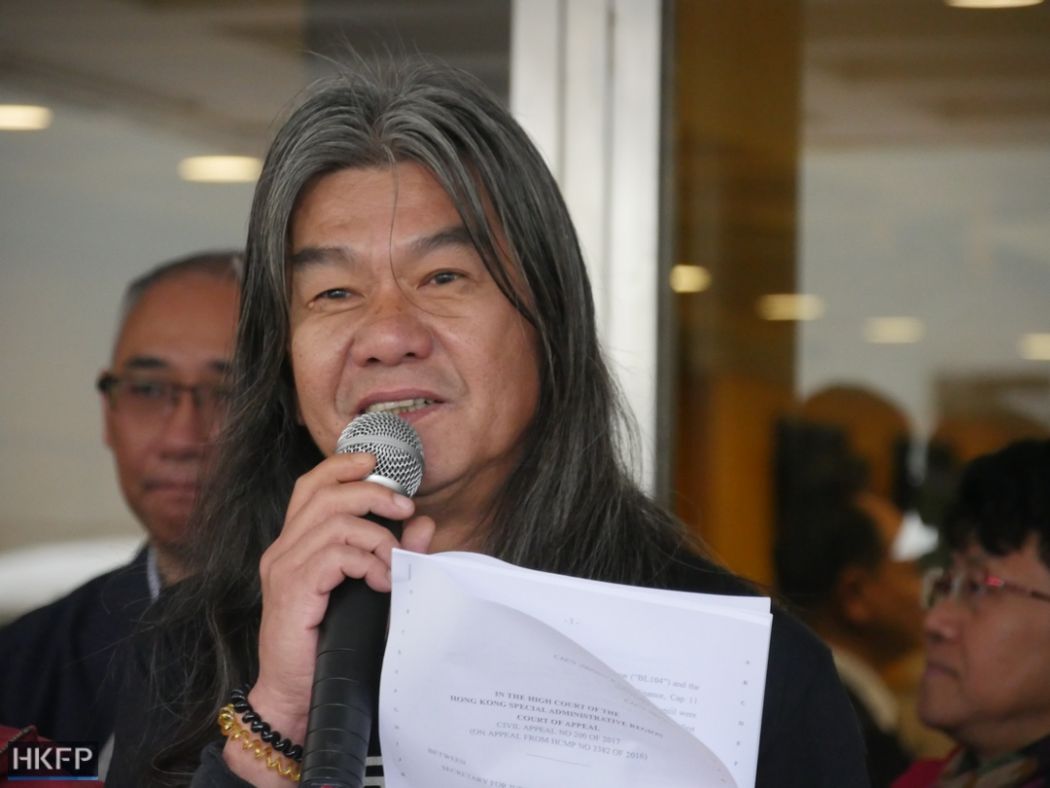

This provoked Beijing to issue its Interpretation of Basic Law Article 104, to mandate sincerity and solemnity in oath-taking. The mandate was then enforced, selectively and retroactively, by Hong Kong prosecutors and judges… targeting the few to teach many a lesson. Six legislators elected in 2016 have now lost their seats. The latest appeal by legislator “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung has just been rejected.

The new vetting procedures are also being enforced, using Beijing’s definitions, to rule that self-determination and independence are one and the same.

Self-determination has been used to disqualify prospective candidates for the follow-up special by-elections to replace the fallen legislators… on grounds of disloyalty to the central government’s sovereign authority.

The main disqualified prospective candidates were Agnes Chow, a member of Joshua Wong’s Demosisto party, and ‘Teacher’ Lau Siu-lai who had hoped to regain the seat she lost due to her part in the October oath-taking protest. Like-minded candidates including Teacher Lau herself were allowed to contest the 2016 election but are no longer as the clampdown proceeds.

Potentially most serious, however, was the disqualification of Legislative Councillor Eddie Chu Hoi-dick. He had no trouble contesting in 2016 and actually won more votes than any other candidate that year. He also escaped retribution for the oath-taking protest.

But Chu has just been disqualified as a candidate for Hong Kong’s lowermost elective office, namely, that of village representative in the suburban New Territories. The election officer failed to give him a pass due to his views on the nature of self-determination and independence.

This case suggests that all the mainstream pro-democracy politicians can be disqualified and barred from participating in future elections since virtually everyone was advocating self-determination by 2016.

Back into the wilderness?

The coup de grace was nevertheless administered not by officials in Beijing or Hong Kong but by Hong Kong democrats and voters themselves, including those who voted and those who did not. This final blow occurred in slow motion during the special by-elections to replace two of the six legislators who were expelled following the October 2016 oath-taking protest. The two were both from Kowloon West. The by-elections were held there last year, in March and November.

But their significance did not register fully until the last votes were counted in late November. Both seats were lost. As a result, the Lunar New Year holiday just ending has been a time not of hopeful anticipation or valiant struggle but for sober reflection about the way forward for Hong Kong’s Democracy Movement.

The questions are especially difficult because they are forcing everyone to concentrate on the reasons for the dual defeat in Kowloon West, and to acknowledge the difficulty of finding solutions.

This has led to more basic doubts about the very rationale for the movement itself… and whether democrats long-standing focus on elections has “failed as a strategy for mobilising support.”

In Kowloon West, the pro-democracy political base with its fractious assortment of old and new pre-and post-Occupy partisans was not strong enough to withstand the impact of the official disqualification strategy. In March and again in November, democratic candidates lost to their pro-Beijing pro-establishment opponents.

But the cause was not so much the disqualification strategy itself as democrats’ inability to work together even to save the two seats lost under circumstances that all alike seemed to deplore as unfair and unjust.

Everyone also knew that as always, their opponents would be disciplined, well-organised, well-funded and above all unified around patriotism and their loyalty to the established order. Because they are working with guidance from on high, they are never allowed to lose sight of the forest for the trees.

They always contest elections for one reason only: to win. Despite valiant efforts on the part of many, Democrats have proved themselves time and again to be incapable of uniting in the same way around their cause.

The thorn in everyone’s side from March through November was ageing moderate Frederick Fung, who cared more about being shunted aside by the younger generation than he did about saving the seat for democrats.

But Fung is also a champion of what democrats in the district know is their Achilles heel: grassroots neighbourhood welfare and livelihood issues. And another inescapable fact of political life for democrats in this respect is that they cannot compete with their well-funded pro-Beijing competitors who specialise in providing community services throughout the city, not just in Kowloon West and not just at election time.

Meanwhile, pre-Occupy rabble-rouser Raymond “Mad Dog” Wong Yuk-man, evidently still miffed about losing to the younger post-Occupy crowd in 2016, kept his distance throughout the by-election campaign.

And committed post-Occupy “localists” could contain their enthusiasm for the democratic candidate, Lee Cheuk-yan, dedicated as he remains to the ideals not of Hong Kong independence but of opposition to “one-party dictatorship” in China.

Of course, if Beijing’s current drive continues and all pro-democracy politicians who have called for self-determination are forced to recant or suffer disqualification, democrats may have no choice but to try and keep their cause alive in ways other than electoral politics.

But that raises the question as to how they might distinguish themselves as democrats and champions of the rights and freedoms that were supposed to be preserved as the distinguishing marks of Hong Kong’s separate system.

For about five years after the British left in 1997, Hong Kong’s Democracy Movement lapsed into disarray. Those were the years between about 1999 and 2003, when the then dominant Democrat Party founded by Martin Lee and Szeto Wah began to fracture under the strain of what they dubbed “birdcage democracy.”

The Democratic Party’s. “Young Turks,” as they were called, began deriding the focus on winning elections to the Legislative Council. They said better to return to the streets than waste time trying to win seats in a powerless “debating club.”

But those were also the years when pro-Beijing forces mastered the art of contesting elections and providing community services that would give them and their allies the majorities they now enjoy on all of Hong Kong’s elected councils.

The democracy movement sprang back to life in 2003, spurred by the perceived dangers in the government’s national security legislation. Everyone belatedly realised the value of seats in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council. It was actually the pro-business Liberal Party that held the balance of power there and saved the day in 2003, by withdrawing support for the government’s national security bill.

The pursuit of electoral reform and genuine universal suffrage has inspired the movement ever since. Until now. But having come so far, everyone can see the promise of elections still receding like a mirage into the distance. It follows that the Lunar New Year holiday just ending has been a time for reflection with no clear view of where to go… except back into the wilderness.