We have all heard of “soft power”. Joseph Nye, Harvard professor, coined the term in the late 1980s to describe influence through the appeal of culture. Based on voluntary attraction, soft power is the ability to “persuade others to do what it wants without force or coercion”. The national culture, benign foreign policies, and political values are the currencies of soft power.

Chinese culture in itself is a potent and appealing commodity, one of fascination and importance since ancient times. Given the state of China’s current political model, however, attracting the wider world on ideological terms remains an uphill battle.

In the political realm, China’s insistence that its policies are beyond reproach has led to the adoption of haughty and overconfident tactics in both domestic and international relations.

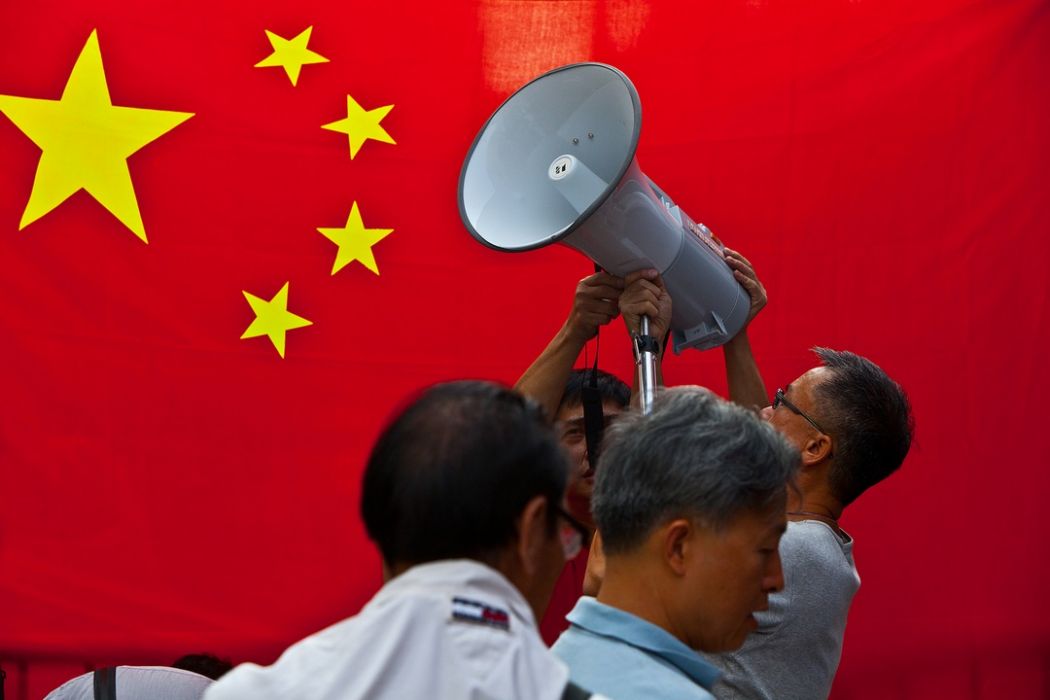

China wants to be accepted on its own terms, and in its own way (with “Chinese characteristics”), but it is acutely aware that the world remains critical of the “harmonious society”. ‘Disharmonious’ voices are silenced, often brutally. Employing strong-arm tactics may muzzle criticism – but only for the moment. Like a multi-headed Hydra, two more pop up in its place.

Exasperation over the poor results of soft power have led to the vexation of China’s political psyche. Frustrations are apparent as ideologues scramble to come up with new ways to woo the world.

But when soft power fails, what comes next? The solution seems to be to ratchet things up a notch. China’s efforts to impact foreign and domestic perceptions while attempting to gain control of the universe of Chinese narrative have left a well-documented trail of objectionable incidents in their wake.

The use of coercive measures to gain influence, having caught the attention of the world, has been given a label. In contrast to soft power, the term sharp power has been coined.

A recent Economist article (Dec 2017) describes China’s adoption of sharp power tactics, as a way of acting based on “subversion, bullying and pressure, which combine to promote self-censorship”. Sharp power is a type of hard power that, suggests Nye, “helps authoritarian regimes compel behaviour at home and manipulate opinion abroad”.

The emergence of China’s sharp power

The CCP is vying for control of the whole China storyline, whether it originates in China itself or overseas. Political analyst Christopher Ford describes the ambition to control all discourse about China, as “conceptual imperialism”, implying that its strategic objective is to control whatever anyone in the world says or publishes about China.

Coercive tactics may (or may not) be legal at home, but when they occur in other countries, they are not taken lightly. With seeming impunity, and little consideration for the backlash, China appears to be thrashing toward a future that, in terms of global public relations, is not going its way.

The campaign, characterized by histrionic episodes if it does not get what it wants, is neither admired nor respected by the international community. In its attempts to silence criticism both at home and abroad, China’s increasing use of threats and intimidation are collectively regarded as unwelcome and malign forays into the darker side of lawlessness. Public examples are abundant.

At the end of 2017, a report on Chinese and Russian influence entitled, Sharp Power: Rising authoritarianism influence was published by the National Endowment for Democracy. It cites Australia as one of the first to call out China’s sharp power on allegations of prying into a number of Australian domains: publishing, universities and most notably, politics.

The discovery led to new laws for restricting “unprecedented and increasingly sophisticated” attempts to manipulate policymakers, what Prime Minister Turnbull called ‘disturbing reports about Chinese influence’. In that same month a Labor senator, Sam Dastyari, resigned after revelations that he had spoken on behalf of China in exchange for payments from Chinese donors with CCP links.

More local incidents (of sharp power in Hong Kong) are the abduction of the four Causeway Bay booksellers; the insistence on loyalty to Beijing for Chief Executive candidates (resulting in the Umbrella Movement); the demand that Legco contenders declare HK is an inalienable part of China; interference in the Legco oath-taking controversy; the sentencing of peaceful young activists, Joshua Wong, Nathan Law and Alex Chow, are only some of the most visible displays of China’s sharp power in action.

This “sharp” end of Chinese soft power in Hong Kong is revealed in a commentary by Lily Kuo. Hong Kong Cantonese papers like Ming Pao Daily, Sing Tao Daily and Sin Pao, owned by wealthy individuals who have businesses in mainland China, have somehow nurtured “close ties to mainland officials” over the years.

Most notably, Kuo points out, at least 10 Hong Kong media owners have been appointed to the CPPCC. Apple Daily, and publications that remain critical of China, suffer advertising boycotts. One of Taiwan’s largest media syndicates, China Times Group, is now controlled by the chairman of ‘Want Want China’, a giant snack and drink company, who said that reunification with the mainland is inevitable.

Also, let us not forget the most recent kidnapping of Swedish citizen Gui Minghai (one of the four Causeway Bay book sellers) by ten plain clothes Chinese police while being accompanied by Swedish diplomats to Beijing.

He later appeared on Chinese TV saying, “My wonderful life has been ruined and I would never trust the Swedish ever again,” adding that he fully regrets taking the train north.

He also called on Sweden to stop ‘hyping up’ his case and said he was considering giving up his Swedish citizenship. Shanghaiist.com reports that human rights observers wasted no time in heaping ‘skepticism and criticism on Gui’s latest “interview.”’

And what was China thinking when it asked Cambridge University Press to hide hundreds of journal articles critical of China from China-based web-users? The decision by CUP was thwarted after enormous public outcry, but a recent article quoting academic experts in the Times Higher Education warns that “Beijing’s efforts could pose a threat to global academic freedom in the future”.

Britain, Canada and New Zealand have also raised the alarm. Canada’s domestic intelligence service warned of government employees and even cabinet ministers that were acting as “agents of influence” for China.

China has also been busy in Europe. Last month the BBC described a German domestic intelligence report that uncovered Chinese operatives using fake LinkedIn profiles to gather information. The purpose was to infiltrate “particular parliaments, ministries and government agencies” targeting “10,000 citizens, including lawmakers and other government employees”.

In December 2017, The Diplomat published an article stating that the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce (in China) issued a strong warning that it will pull out of China if the “CCP continues its attempt to interfere with internal business”.

The protest was over Chinese demands that Party members be brought into management; that CCP organizational expenses be paid by the company; and, that the foreign company’s Chairman of the Board and the CCP Secretary be the same person.

A recent Free Beacon (July 2017) report revealed the extent of Chinese intelligence agents in the US – a network of approximately 25,000 operatives.

Enormous pressure from China was placed on the Nobel Committee to backtrack on Liu Xiaobo’s Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. Norway’s decision to proceed with the award resulted in economic punishment from China, not to mention a steady stream of vituperation in China’s English media, denigrating Norway, the Nobel Prize, the Committee, and, in a very personal attack, Thørbjorn Jagland, Chairman of the award committee.

Punitive actions have also been highlighted by long-time China scholar Perry Link, who writes of “blacklists” of journalists and academics who can’t get Chinese visas because of their research on sensitive issues related to human rights, Xinjiang, Tibetan independence, or Taiwan independence. His article, The Long Shadow Of Chinese Blacklists On American Academe (2013), has much to say about this phenomenon. Researchers who have been critical of the Chinese government are forced to recant, or even worse, self-censor by aborting research into forbidden topics.

In her study of Chinese control tactics, The Long Shadow of Chinese Censorship, Sarah Cook writes that: “The dynamics are subtle, but the reality is that the “China Factor” exists in newsrooms around the world, be they internationally renowned outlets such as the New York Times and Bloomberg, a local newspaper in Nepal, or a Chinese radio station in Los Angeles….” The Chinese government’s efforts to influence reporting by foreign and overseas Chinese news outlets have intensified and expanded over the past five years.

A glaring paradox

Even the blind can see a glaring paradox. In the global scheme of things, the more that China’s sharp power becomes evident, the less value is accorded to its soft power. But the ironic reciprocity of this arrangement is lost on China’s leaders.

Soft power is not coerced. It comes from inspirations within civil society – not the government. Given the examples above, it is not difficult to say that China’s efforts to control the China narrative remain an increasingly fraught and distant goal. Nye wrote that China does not understand that soft power initiatives are rendered impotent by oppression and coercion, whether domestically or overseas.

Ideological haughtiness robs China of the ability to evoke a level of charisma capable of appealing to the rest of the world. Resorting to sharp power tactics as a go-to strategy reveals a deep frustration at being unable to control criticism through the gentler means of persuasion and attraction.

Until the ideological divide can be bridged, China will continue to struggle with the age-old question of how to present itself to the world.