China, which British Prime Minister Theresa May visited last week and with which the Vatican has reportedly signed a controversial deal, is a land of euphemisms. Underneath the glistening bright towers of economic growth, the vicious strangulating repression of the Communist regime lurks, and under Xi Jinping its reach has widened and its brutality intensified. Xi’s regime has perfected an ability to twist truth as it twists the necks of dissidents, and turn the rule of law into rule by laws that legalise barbaric torture. American scholar Perry Link once aptly described the ‘anaconda in the chandelier’ in China’.

One of the latest euphemisms is the peculiar term “residential surveillance at a designated location” (RSDL). It sounds mild compared to imprisonment; it sounds like you might simply be monitored at home, or held under some form of house arrest. In truth, it’s the very opposite – a licence to disappear people in the middle of the night, to an unknown location, to torture with impunity. Hotel rooms, the backs of restaurants, offices and empty apartments are transformed into secret torture chambers.

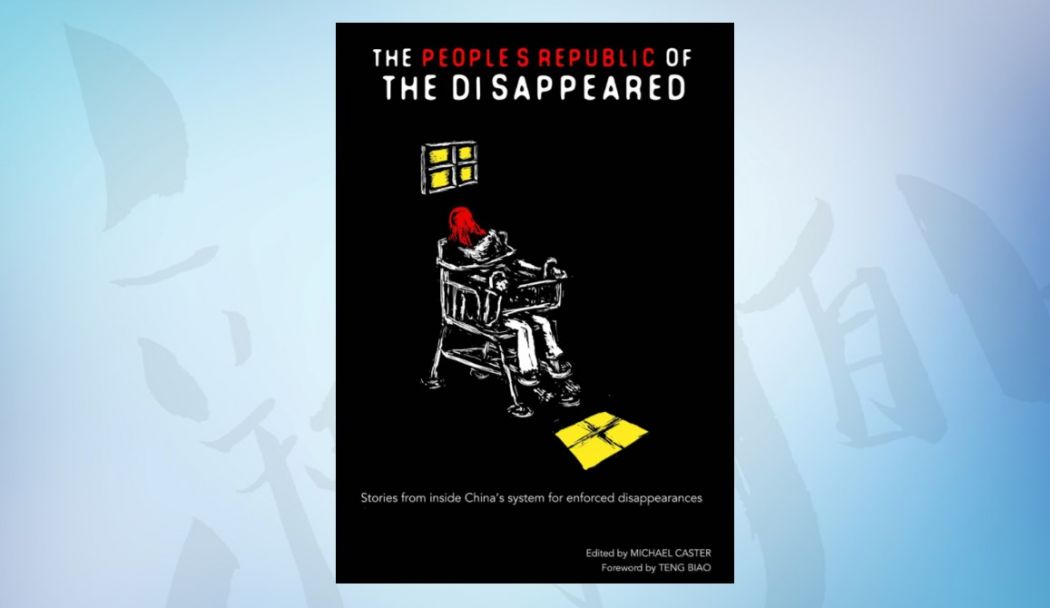

A new book, The People’s Republic of the Disappeared, documents what happens under RSDL – it is the first of its kind to do so. A compilation of testimonies edited by American human rights activist Michael Caster, it paints a chillingly consistent picture of a land of lies, intimidation and physical and psychological torture.

The book’s twelve chapters are written mostly by Chinese dissidents who have survived RSDL. One chapter is written by Peter Dahlin, a Swedish activist who was arrested and placed under RSDL in 2016, and another by his girlfriend, Pan Jinling, – an account of someone detained under RSDL not for any political activities of her own, for she was not an activist at all, but simply for being Peter’s girlfriend – ‘guilt by association’.

Teng Biao, a well-known exiled Chinese lawyer, defines RSDL in the Foreword as “a system for prolonged, pre-trial detention outside a formal, legal location” but one which includes “a more severe, more terrible coercive measure than normal criminal detention”. RSDL, he adds, “is not limited by detention centre regulations, nor any real supervision at all. The chances of torture are greatly increased; in fact, torture has become rampant under RSDL.” The forms of torture include “long periods of sleep deprivation, beatings, electrocution, forcibly handcuffed and shackled, ….subjected to stress positions, denial of food and water, … extensive and continuous interrogation sessions, threats of violence, or threats to family. Everyone placed in RSDL is kept in solitary confinement.”

The suddenness of abductions of dissidents and activists taken into RSDL is shocking. Lawyer Wang Yu recalls the night the police came for her, the lights in her house were cut “without warning”. Before being able to telephone for help, she writes, “someone had already broken through the door, and was instantly upon me. The light from his headlamp flashed into my face.” She was handcuffed behind her back, pushed onto a bed and a black hood was forced over her head.

Human rights lawyer Liu Shihui claims he was beaten so badly in RSDL that he needed stitches. “I realized I was in a place where the law does not exist, a black hole, a camp controlled by monsters,” he writes. Activist Tang Jingling was not allowed to sleep for ten days. Jiang Xiaoyu, an IT worker, was told by a security agent: “I can make you disappear for years. Even your wife and daughter won’t know where you are.” Lawyer Xie Yang was told: “We’ll torture you to death just like an ant,” and he recalled that if they had gone that far, “my family wouldn’t even know.”

The threats to a prisoner’s loved ones are among the most insidious forms of mental torture. Xie Yang was told that the lives, job prospects and educational opportunites for his wife, his brother and his daughter could be ruined. “Your wife and children need to pay attention to traffic safety,” he was warned. “If you don’t cooperate with us, we can investigate your friends, one by one, and put them through the wringer … We’ll go after whomever we please and deal with them however we want.”

Peter Dahlin’s girlfriend Pan Jinling was shown receipts of payments allegedly made by Peter to an ex-girlfriend, claiming that he was having an affair. She was shown a photograph of a baby, in an attempt to convince her that Peter had a family outside China. Then, the pressure became even more serious. She recalls: “They read the law I was supposed to have broken, a crime they said carries from five years to life imprisonment. They told me my boyfriend had placed all responsibility on me – I knew this wasn’t true. By warning me that I could be named as the mastermind they could threaten me with serious consequences if I didn’t defend myself, that is, I could accuse my boyfriend to save myself. I remembered hearing somewhere that this is called the prisoner’s dilemma.” Pan Jinling, however, saw what they were attempting to do and refused to be broken. “I knew they were just trying to defame him, and didn’t argue or disagree, choosing silence as my strategy … I would not betray him.”

The purpose of such torture, writes Liu Shihui, “is simply to destroy you: to break you using any form of torture they want or feel is needed. Even more, it is used to make people in the community doubt each other, to make you incriminate not only yourself, but also others, to break the community.”

Tang Jitian says RSDL is “evil … worse than death for most of its victims”. As Michael Caster argues, enforced disappearances are a crime under international law, constituting a crime against humanity. He leaves it to the reader to decide whether RSDL amounts to such a crime, but he concludes that however we regard it, China and its “war on human rights” cannot be ignored. “What China does arguably concerns everyone,” argues Caster. “China has proven that it is more than happy to share its repressive tactics with its neighbours, or to simply impose its will over them.” Furthermore, the victims of RSDL are not only Chinese citizen: Taiwanese pro-democracy activist Lee Mingche, and Swedish citizens Peter Dahlin and Gui Minhai, a Hong Kong-based bookseller, were abducted and secretly detained.

The People’s Republic of the Disappeared is a profoundly important book. If you want to understand China beneath the dollar signs and infrastructure projects, read this book. If you want to have a fuller, complete picture of China and the regime’s mindset and behaviour, read this book. If you have a mind, a soul and a heart and a desire to see a better China and a better world, read this book. It is time to strip aside the euphemisms and speak out against China’s barbaric crimes.