Trying to hold the government to account in court almost always guarantees a David and Goliath scenario: the government has unlimited resources to fight legal battles, while civilians seeking to rectify injustices face systemic obstacles at every step of the judicial process.

But in Hong Kong, one man is unfazed by the challenge. Cheung Chau resident Kwok Cheuk-kin – widely known as the “king of judicial review” – has taken the government to court more than 20 times over the past decade, though he has only won once.

The talkative 78-year-old may look like an unassuming elderly retiree, but he is a familiar figure to those on the judicial scene. When Kwok posed for pictures in front of the High Court during our interview, several security guards gave him a nod and a smile.

Inspired by Long Hair

Kwok holds a law degree from a Taiwanese university. He said he worked at Hong Kong’s justice department for a few years before he was jailed for participating in a Baodiao – or “defend the Diaoyu Islands” – campaign in the 1970s.

Then in 1989, Kwok was detained by the Chinese authorities for a year after joining the Tiananmen protests. “I escaped by smuggling sleeping pills and putting them in the drinks of the guards,” he said, “then I ran away, but I didn’t go south because of the tight security measures.” Instead, he smuggled himself to Russia and then took a plane to Germany before flying back to Hong Kong.

Despite working as a clerk at law firms for many years, Kwok only filed his first judicial review after his retirement in 2006. It was over the increase of First Ferry fares. He said he was inspired by lawmaker and social justice activist “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, who often appears in court as an applicant or defendant, sometimes without lawyers.

Kwok lost his first judicial review challenge five years later. But the defeat did not stop him pursuing more judicial reviews against the authorities over various issues, such as the controversial Small House Policy and the HKTV free-to-air licence saga.

Though Kwok is hailed as a hero by some in the pro-democracy camp, the court has criticised some of his applications for being an “abuse of process” or initiated “without a clear understanding” of the issues.

In recent months, Kwok made headlines by filing a number of judicial review challenges against Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying and pro-Beijing lawmakers over the legislature’s oath row. When asked to comment on the controversy, the elderly man took out his well-worn copy of the Basic Law while reciting the provisions in Hong Kong’s mini-constitution that he argued Leung and other politicians have violated.

“I’m not physically capable enough to participate in protests and challenge the police cordons, so I can only rely on judicial reviews,” Kwok told HKFP.

Asked if he believes judicial review is an effective means of seeking justice, Kwok said: “It is justice when you win.”

But Kwok, who has been fighting in the courtroom for the last 10 years, thinks that his chances of winning are not determined solely by the strength of his legal arguments, but there are other decisive factors: judges and the legal aid system.

Justice in our judicial review system?

Judicial review is a formal mechanism for keeping public bodies in check. It mainly reviews administrative decisions they make, and looks at whether a law or administrative decision is compatible with the Basic Law.

Critics – including incumbent leader Leung Chun-ying and retired Court of Final Appeal judge Henry Litton – argue that judicial reviews have been abused. Others accuse the Legal Aid Department of giving out funding too easily.

During a rare opportunity to speak publicly, Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma Tao-li defended the judicial review system last year, saying that the resulting decisions serve as a guide to good governance, even if they may occasionally cause inconvenience.

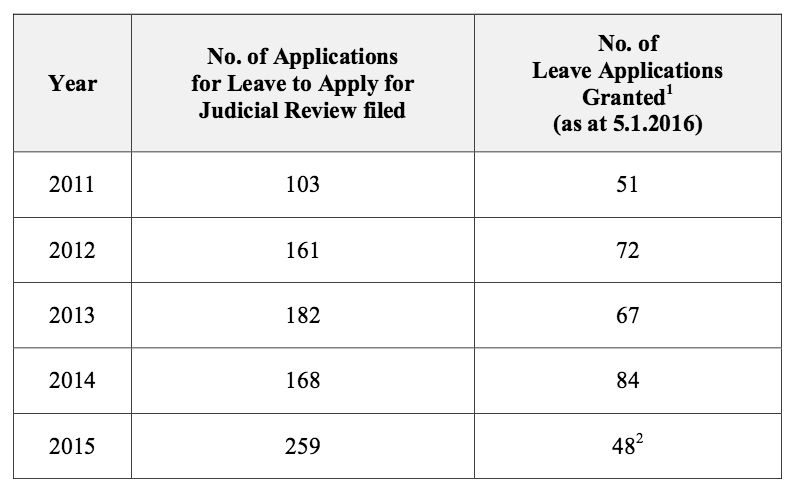

The High Court has consistently accepted less than half of applications between 2011 and 2015. The number of judicial review applications granted leave accounts for a tiny portion of the judiciary’s caseload. For example, the Court of First Instance had around 20,000 first instance civil litigation cases in 2015, whereas only 48 leave applications for judicial review were granted that year.

A frequently cited reason for not granting leave is the lack of legal merit, but legal scholar Karen Kong argues that the courts have generally been reluctant to deal with issues intertwined with politics, due to the conservative attitude of some judges.

This is a view shared by Kwok, though he expressed the criticism more bluntly. “Judges constantly move the goalposts,” he said.

“Some judges make decisions based on what they think the government prefers. In many judicial review cases, the applicants should have won but the court found many reasons to justify ruling in favour of the government.”

Kwok gave the example of his judicial review over the government’s controversial decision in 2012 to bar lawmakers from running in a by-election within six months after they resigned from the legislature. He criticised the government for violating the constitutional right to stand for election.

“Judge Thomas Au of the Court of First Instance, as well as the Court of Appeal, said it is a political issue pertaining to the legislature and the court should not interfere,” he said. “But then, how come the two courts decided to interfere in the [oath-taking saga] of Yau Wai-ching and Baggio Leung Chung-hang this time around? Many people did not see this coming.”

Generally, the courts respect the decisions of the legislature based on the principle of separation of powers. The court has also emphasised in previous judgments that it should exercise its jurisdiction over the legislature’s affairs in a “restrictive” manner.

But last November, Judge Au of the Court of First Instance and three Court of Appeal judges rejected the legal argument made by counsel for Yau and Leung that the court should stay out of the political dispute. They ousted the duo from the legislature for staging a controversial protest during a swearing-in session.

The court’s decisions to intervene in the oath dispute drew criticism from the public and the legal sector. Barrister and ex-lawmaker Audrey Eu has suggested that the impact on the city’s rule of law would have been less damaging had the court remitted the decision to the legislature’s president for his reconsideration.

While some legal scholars believe conservatism may explain why most judges tend to adopt a pro-establishment position, Kwok has a different theory for it.

“Judges in the lower courts could get promoted to the Court of Final Appeal. Who doesn’t want to climb the ranks and become rich?” he said. “But it’s different at the Court of Final Appeal, because the judges there are already at the top. So they may have other motivations: to gain a reputation for being fair, so that they may get the opportunities to sit on international hearings.”

While Kwok’s opinion remains speculative, he is not alone in thinking that the courts are biased: there has been an increase in online comments sharing Kwok’s sentiment in recent years. With Hong Kong’s justice system being dragged into political debates, legal scholar Eric Cheung Tat-ming has warned that public perception of judicial independence and fairness is an important indicator of the rule of law.

Legal aid and access to justice

A factor that discourages people from pursuing judicial reviews is the high litigation cost. While Hong Kong has a legal aid system in place, critics argue that it is not enough to ensure equal access to justice.

In 2013, former Bar Association chair Kumar Ramanathan criticised the “institutional inertia” of the Hong Kong government to widen the scope of cases where legal aid is made available. “Where there is no legal protection, there is in effect no law. In so far as Hong Kong citizens are precluded from access to the Courts, the rules of the law which they would like to invoke are for them as good as non-existent,” he warned.

The success rate for legal aid applications for judicial review cases remained at about 25 per cent between 2011 and 2015. Applicants who press on without legal aid can be ordered to pay the government’s legal costs if they lose.

This was what happened to Kwok during the 2015 lead water scandal. While Kwok received legal aid for most of his past judicial review cases, he was not given legal aid when the court went ahead to review the government’s handling of the water crisis. He lost and – without legal aid – was ordered to pay the government over HK$500,000 in costs. He said the government had not yet pursued him for the amount.

A limitation of the legal aid system, Kwok claimed, is that lawyers assigned by the Legal Aid Department do not put much effort in the cases and “so if you win you are already very lucky.”

He also said that in his experience, the legal aid system played a decisive role in his access to court.

The Legal Aid Department may seek advice from independent lawyers on the merit of an application. Kwok found this process arbitrary, partly because he believed the choice of lawyer effectively decided whether he would be given legal aid.

“If they don’t want to give you legal aid, they can find a pro-establishment lawyer… It is always possible to justify not giving out legal aid,” he said. “But if they want you to go ahead, they can find a pan-democrat [lawyer] such as Audrey Eu, who will write something good about your case.”

The Legal Aid Department told HKFP that Kwok’s allegation was “totally unfounded.” It said that it will consider evidence and relevant legal principles in deciding whether an application is meritorious. In the absence of precedent, it will select lawyers for giving independent legal opinion according to a list of criteria, including their level of experience and area of expertise.

“Political inclination and ideology are not among those criteria to be considered,” the department said. It added that if an applicant is denied legal aid, they can appeal against the decision to the Registrar of the High Court.

Making enemies

Kwok’s activism has brought him unwanted attention too. For the first time, Kwok was featured on the front page of the Beijing-backed paper Ta Kung Pao last December. The paper’s investigative team claimed that Kwok had “interwoven relationships” with the Democratic Party on the basis that he “constantly texted legal questions” to a lawyer employed by Albert Ho, lawyer and ex-chair of the Democratic Party.

In another article, it accused Kwok of responsibility for illegal structures at his residence in Cheung Chau, though it only mentioned at the end of the story that Kwok was just a tenant of the property.

Kwok also made enemies among Cheung Chau leaders after he won a judicial review case in 2015 over unlicensed funeral parlours on the island. He said the rural leaders still verbally harass him to this day out of resentment that he shut down their business.

But he said he was not troubled by the harassment. “I just laugh at it,” he said. “As for my neighbours, I am on good terms with them because I help them with drafting letters to the government. I have my own strengths.”

Even though Kwok has received help from pro-democracy lawyers, he said he prefers taking action alone over having allies.

“I don’t want to be affiliated with any group, because our ideologies may conflict. If I file a judicial review challenge over an issue that affects the interests of a political party I’m associated with, that’d be tricky,” he said.

Unmarried and single, Kwok said he has no family burden and can therefore risk going bankrupt should he lose a lawsuit. Asked if he has other hobbies besides his courtroom activism, the elderly man’s first reaction was: “No, I don’t.”

He then continued: “I take care of my pets – I have one dog and three cats. Sometimes I go fishing. I also grow vegetables for my own use. That’s all I do.”