Last week’s policy address by Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying – which amounted to a dastardly two-hour dodge of all the issues most Hong Kong people want to talk about – makes this city’s predicament uncomfortably clear: the man who masquerades as its leader is actually nothing more than an obedient footman who – when he is not mouthing One Belt, One Road platitudes to please his masters in Beijing – is promising to spruce up our toilets.

With the city beset by concerns over the disappearance of Lee Bo – only the latest of five booksellers associated with Causeway Bay Books to vanish under circumstances that look suspiciously like abduction by mainland authorities – and by fears that core Hong Kong values such as freedom of expression and the rule of law are under threat, our toady-in-chief chose to not even acknowledge, let alone allay, any of those serious misgivings.

It was a remarkably insensitive, deliberately purblind performance that, in any fully democratic system, would have resulted in Leung’s ouster as chief executive in the next election. Instead, however, in the strangely perverse politics of Hong Kong, by turning his back on his own people, Leung may have all but assured his re-election in 2017 by a 1,200-strong election committee stacked by the very Chinese leaders his speech was aimed to please.

And please them it surely did. Leung kowtowed to the north no fewer than 48 times with ringing endorsements of President Xi Jinping’s 21st-century vision of reviving the old Silk Road of China’s glorious trading past in a massive new effort that involves building rail links and new port facilities designed to move heavy Chinese industry to cheaper, less-developed countries and to greatly increase demand for Chinese products, not to mention its alternative development model to the West.

Leung exhorted Hong Kong companies to cash in on the infrastructure and trade boom to be generated by One Belt, One Road and, among other measures, proposed scholarships to Hong Kong universities for students in countries along the new Eurasian trade route and exchange programs that would allow Hong Kong students to study in countries such as Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Leung conveniently failed to mention criticisms of Xi’s grand scheme – that it will be a vehicle not just for the export of Chinese goods and industry but also for Chinese corruption and authoritarian-style rule. Which, of course, is exactly what people in Hong Kong fear is being exported to their own city from the mainland, with Lee Bo now serving as the latest frightening example.

Lee was last seen on December 30 and, ever since, his mysterious disappearance has been front-page news in Hong Kong. It has caused a stir in the international media as well. Yet the putative leader of our city did not deem Lee important enough for mention in a two-hour speech that is supposed to address the issues that most concern Hong Kong’s 7.2 million people.

The omission is simply unconscionable. The Leung administration may point out that the chief executive answered questions about Lee’s disappearance both before and after his policy address, but that just underscores the bookseller’s parenthetical status for Leung and his ministers, who are clearly stalling on his case as they await directives from Beijing.

Pressured by both the local and international attention that Lee’s vanishing act has attracted, Hong Kong authorities began making official inquiries to their mainland counterparts nearly three weeks ago. The response has been an alarming, if also predictable, silence.

We have heard from Lee himself, however, whose fax and video messages claiming that he is voluntarily assisting in an investigation and urging demonstrators to stop their protests on his behalf seem directed by someone behind the curtain and thus only deepen the mystery and anxiety over his case.

It’s way beyond time for the Leung administration to speak out forcefully about Lee’s fate – as well as the fates of the other four booksellers who have melted away over the past three months but who were not in Hong Kong at the time of their disappearance. The chief executive’s annual policy address would have been the best time for him to acknowledge and share in the widespread disquietude that these cases have produced in the city.

This isn’t just about Lee, his compatriots and one bookstore, now shuttered in fear, that specialised in salacious tomes detailing the private lives of China’s political elite, including Xi.

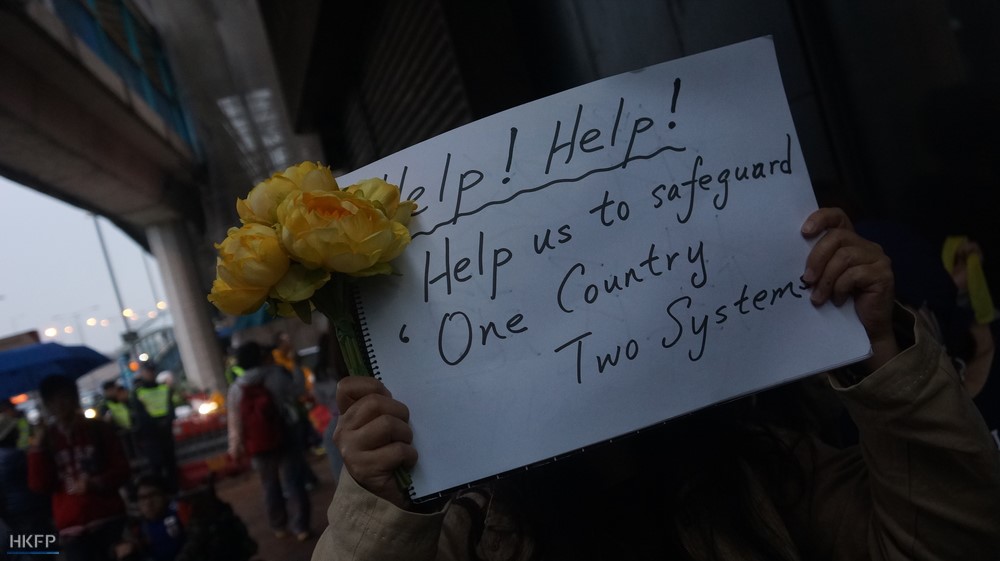

It goes right to the heart of the “one country, two systems” formula that is supposed to guarantee for the next three decades that Hong Kong remains a special administrative region of China with a constitution that enshrines the rule of law, safeguards free expression and protects its citizens from the kind of illegal detention that may well have occurred in Lee’s case.

It’s certainly worthy of a line or two in the chief executive’s policy address. How about at least one expression of concern over Lee and only 48 kowtows to One Belt, One Road?

Our chief executive could not even muster that, however.

That said, Leung’s speech was not devoid of good ideas: his welcome, if belated, pledge to ban the trade and sale of ivory in Hong Kong was certainly one of them. But how can non-slip surfaces for public toilets and a few additional seats at bus stops receive more attention than five missing booksellers who have become international symbols of the cherished freedoms and legal protections that so many Hong Kong people now feel are under threat?

Critics complain of the loud and disruptive protest tactics that have become the stock-and-trade of pan-democratic lawmakers whose political lives seem dedicated to frustrating and embarrassing Leung at every turn.

In this case, what else are they supposed to do when the man who is tasked with running the city in the best interests of those who live here wilfully abdicates that role?

Somebody needs to stand up and shout about it.